Star Trek: The Next Generation – Season 3 – “Hollow Pursuits”

Is there really not a book on holodiction yet?

Have you ever enjoyed a story so much that you wished it wouldn’t end? Have you ever experienced a fiction so powerful that it felt “real” to you? Have you ever had a hard time letting go of something you could never even hold to begin with?

The characters in Star Trek: The Next Generation haven’t. And they even had the perfect excuse, the ultimate in escapist fantasy: the Holodeck.

First introduced in the pilot of Star Trek: The Next Generation, the Holodeck was an augmented reality so perfect that the assets it presented to its users felt, smelled and tasted real. Crew members could program the Holodeck any way they wished — but if they weren’t specific enough, the Holodeck could procedurally generate programs that grew almost beyond the users’ control. This was the plot, of course, for many a TNG episode.

[pullquote]You get the sense that the writers were more excited about the Holodeck’s potential for enabling wacky, elaborate plot lines than the characters were about what we would today consider the coolest, most powerful and most dangerous videogame ever.[/pullquote]

In the first two seasons of TNG, for both the characters and the show’s writers, the Holodeck was a near-limitless device for entertainment and wish-fulfillment. But you get the sense that the writers were more excited about the Holodeck’s potential for enabling wacky, elaborate plot lines than the characters were about what we would today consider the coolest, most powerful and most dangerous videogame ever.

Season 1 devotes several episodes to introducing the concept of the Holodeck, but the episodes forgo any difficult philosophical exploration for the sake of fairly straightforward science fiction escapades. In “The Big Goodbye” (1×12), Picard talks about trying out the “new Dixon Hill program” as if it’s the latest book or TV episode in his favorite series. The program in question is like an elaborate videogame, where Picard takes on the titular role of Dixon Hill, a private investigator in 1940s San Francisco. It’s implied that there are more of these Dixon Hill stories, but the background of such apparently serialized Holodeck narratives is never explored. Is there a writer or a studio responsible for creating Dixon Hill programs? Are they sent directly to the Enterprise, or perhaps published on some sort of Starfleet Holodeck version of Steam or Xbox Live? Would other crew members have played “the new Dixon Hill program”? Would Picard be in danger of overhearing spoilers if he were to venture into Ten-Forward before he finished the story?

These questions are never explored in “The Big Goodbye,” but just three episodes later, in “11001001” (1×15), we see a different type of Holodeck program: a woman named Minuet. Minuet is a sort of tech demo. A race of technologically-advanced aliens called the Bynars added her to Riker’s existing jazz bar simulator to demonstrate the power of their programming skills — and also to keep Riker trapped in the Holodeck while the Bynars use the Enterprise’s computers for their own purposes. As in “The Big Goodbye,” this episode gives little thought to the actual mechanics of the Holodeck. What makes Riker deem Minuet “practically self-aware”? What is it about Minuet that makes her stand out from other Holodeck programs? Why did Minuet vanish at the end of the episode, and just how deep an impression did “she” make on Riker?

Both episodes toy with the idea that the Holodeck has the potential to impact the real world. In “The Big Goodbye” the characters in the Dixon Hill story “learn” that they are part of a story and ask Picard if they will continue to exist when Picard leaves the Holodeck, and in “11001001” Riker expresses genuine fondness and even longing for Minuet. But both these moments are portrayed as highly unusual. They’re tossed into their respective episodes right at the end, almost as an aside.

Both episodes toy with the idea that the Holodeck has the potential to impact the real world. In “The Big Goodbye” the characters in the Dixon Hill story “learn” that they are part of a story and ask Picard if they will continue to exist when Picard leaves the Holodeck, and in “11001001” Riker expresses genuine fondness and even longing for Minuet. But both these moments are portrayed as highly unusual. They’re tossed into their respective episodes right at the end, almost as an aside.

Whether the characters are trapped accidentally (as in “The Big Goodbye”) or intentionally (as in “11001001”), the Holodeck is portrayed as a location isolated from the rest of the Enterprise, clearly delineated by doors and walls. Any blurring of the lines between Holodeck and “real world” that occurs in these two episodes is portrayed as aberrant. We’re meant to understand that the characters usually treat the Holodeck like a novelty.

By and large, the characters of TNG show very little concern about the Holodeck’s existence in the first place. No one seems to have any lasting difficulty identifying where the Holodeck ends and “real life” begins. It isn’t until Season 3 that the Holodeck’s potential for encouraging the darker side of fantasy is addressed. It’s first touched upon in “Booby Trap” (3×16), when the Enterprise’s engine is compromised and Geordi LaForge, the chief engineer, creates a holographic simulation of the scientist who designed it to help him fix it. Almost on a whim, LaForge asks the computer to simulate a personality for the program as well, and the result is so realistic that LaForge ends up falling in love with her. However, once the crisis is averted LaForge expresses little difficulty in deactivating the program, saying, “I’ve always thought that technology enhances the quality of our lives…but sometimes you just have to turn it all off.” A season later, in “Galaxy’s Child” (4×16), the real scientist arrives on the Enterprise and actually stumbles across the program LaForge created of her. Taken out of context, the program seems like a romantic simulator, and the scientist is furious, telling LaForge she feels “violated.” However, when LaForge explains the situation and apologizes she forgives him, and in a possible future shown in the series finale, the two appear to be married.

There’s only one episode of TNG that addresses an instance where a crewmember’s use of the Holodeck was considered dangerous and obsessive. And there, it’s implied that the character wasn’t quite right to begin with.

The first half of the episode “Hollow Pursuits” (3×21) is largely devoted to giving the rest of the Enterprise the chance to tell us about Lieutenant Reginald Barclay — or, as his coworkers in Engineering call him behind his back, “Broccoli” — and most people don’t have anything nice to say. Barclay has all the classic symptoms of a social anxiety disorder: he stammers, doesn’t make eye contact and is easily cowed by his more assertive coworkers (especially the brilliant teenager Wesley Crusher). According to his Starfleet psychological profile, he has a history of “seclusive tendencies.” Apparently “seclusive” is cause for concern in the 24th century: Barclay was “noted” for it at Starfleet Academy more than once. He’s “always” late for work, frequently distracted and puts in the minimum amount of effort to “slide by,” and by the time the episode begins Geordi has had enough of it. “Broccoli makes me nervous, Captain,” Geordi tells Picard. “He makes everyone nervous.”

The first half of the episode “Hollow Pursuits” (3×21) is largely devoted to giving the rest of the Enterprise the chance to tell us about Lieutenant Reginald Barclay — or, as his coworkers in Engineering call him behind his back, “Broccoli” — and most people don’t have anything nice to say. Barclay has all the classic symptoms of a social anxiety disorder: he stammers, doesn’t make eye contact and is easily cowed by his more assertive coworkers (especially the brilliant teenager Wesley Crusher). According to his Starfleet psychological profile, he has a history of “seclusive tendencies.” Apparently “seclusive” is cause for concern in the 24th century: Barclay was “noted” for it at Starfleet Academy more than once. He’s “always” late for work, frequently distracted and puts in the minimum amount of effort to “slide by,” and by the time the episode begins Geordi has had enough of it. “Broccoli makes me nervous, Captain,” Geordi tells Picard. “He makes everyone nervous.”

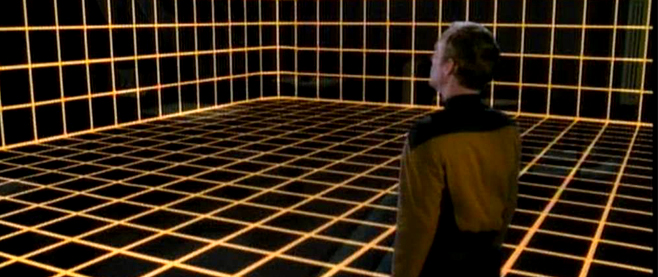

But this isn’t the Barclay that the audience first meets. The episode opens on Barclay at the bar in Ten-Forward, pouring himself a drink as he casts a boldly flirtatious look at Deanna Troi. “I don’t want any trouble here, Barclay,” Guinan tells him firmly. “Anywhere you go, trouble follows.” Barclay proceeds to mouth off to Geordi, beat up Riker, insult Picard and seduce Troi, and then, just when the viewer is thoroughly confused, Barclay says the magic words that turn the carriage back into a pumpkin: “Save program.” Troi, Riker and the rest of Ten-Forward all fade away, leaving Barclay standing in the grid-patterned cube that is the Holodeck’s true interior. He casts a nervous glance around him, straightens his uniform and walks out. The camera lingers on the Holodeck’s inner doors as they slide closed behind him.

Barclay, it turns out, uses the Holodeck to enact real-life social scenarios — with a few changes. In Barclay’s programs LaForge and Riker are pushovers, Wesley is a petulant brat, Troi is a sex goddess and Barclay is always the hero. In the Holodeck, he can practice the same encounter with Riker over and over again. He can think of new and cleverer ways to tell LaForge off. He has control.

Through LaForge, we learn that Barclay’s use of the Holodeck is very different from that of a “normal” 24th century citizen. “It is kind of unusual, recreating people you already know,” LaForge says, even though he himself had done something similar just a few episodes earlier. “I don’t know,” he adds, “there’s a part of this that’s kind of therapeutic.” LaForge seems intrigued by the idea of the Holodeck being used for therapeutic purposes, like he’s never considered it before. His comments give Barclay the chance to deliver a speech that perfectly encapsulates why he is such an outsider in the well-adjusted world of the 24th century:

Through LaForge, we learn that Barclay’s use of the Holodeck is very different from that of a “normal” 24th century citizen. “It is kind of unusual, recreating people you already know,” LaForge says, even though he himself had done something similar just a few episodes earlier. “I don’t know,” he adds, “there’s a part of this that’s kind of therapeutic.” LaForge seems intrigued by the idea of the Holodeck being used for therapeutic purposes, like he’s never considered it before. His comments give Barclay the chance to deliver a speech that perfectly encapsulates why he is such an outsider in the well-adjusted world of the 24th century:

“When I’m in [the Holodeck]… I’m just more comfortable in there. You don’t know what a struggle this has been for me, Commander…Being afraid all the time of forgetting somebody’s name. Not knowing what to do with your hands. I am the guy who writes down things to remember to say when there’s a party and then, when he finally gets there, he ends up alone in a corner trying to look comfortable examining a potted plant.”

“You’re just shy, Barclay,” says LaForge.

Barclay laughs. “Just shy. Sounds like nothing serious, doesn’t it.” He shakes his head. “You can’t know.”

If not shyness, then what, exactly, is Barclay’s problem? None of the characters are able to articulate it, or even to assure us that Barclay does, in fact, have a problem to begin with. If we take Guinan’s advice — as the audience is so often supposed to — Barclay doesn’t have a problem at all. He’s merely “imaginative.” “I just serve him [warm milk] and let him be,” she tells LaForge with one of her mysterious smiles. The other characters aren’t as tolerant. The episode frequently suggests that Barclay’s relations with the Troi hologram were inappropriate: the scene in which Barclay first talks to the real Troi, for example, is full of double entendres (“Have you ever been with a counselor before?” “Yes…No!”).

In the utopian vision of Star Trek, where the heroes are all marvelously well-adjusted pollyannas and the antagonists are black-and-white personifications of philosophical quandaries, Barclay’s possibly sexual and definitely improper relationship with the simulation of Deanna Troi alone could have been enough to condemn him as a character. But it’s mostly played for laughs in the episode. It’s unfortunate, because Barclay had all the makings of Star Trek’s first anti-hero.

Ultimately, “Hollow Pursuits” doesn’t commit to any actual exploration of anxiety, “holodiction” (LaForge’s word for Holodeck addiction) or the Holodeck’s uses in 24th century culture. Instead we get a cheesy wrap-up in which Barclay saves the ship from a random problem-du-jour that had been plaguing the sensors. “Glad you were with us out here in the real world, Mr. Barclay,” LaForge congratulates him, causing Barclay to blush and smile. Based on the plot alone, the lesson is clear: being in the Holodeck is a dangerous distraction from the “real” world.

Ultimately, “Hollow Pursuits” doesn’t commit to any actual exploration of anxiety, “holodiction” (LaForge’s word for Holodeck addiction) or the Holodeck’s uses in 24th century culture. Instead we get a cheesy wrap-up in which Barclay saves the ship from a random problem-du-jour that had been plaguing the sensors. “Glad you were with us out here in the real world, Mr. Barclay,” LaForge congratulates him, causing Barclay to blush and smile. Based on the plot alone, the lesson is clear: being in the Holodeck is a dangerous distraction from the “real” world.

It’s a perfect happy ending. But through the lens of a twenty-first century viewer (or maybe just this twenty-first century viewer, but somehow I doubt I’m the only one), “Hollow Pursuits” isn’t really a lesson in proper Holodeck usage. It’s about a non-neurotypical person in a society too cohesive, too well-adjusted to understand him. It’s about a “real world” that is alarmingly unequipped to give Barclay the help he needs to cope. Not even Troi, the ship’s counselor, seems able to understand or properly diagnose him, at least not at first; the breathing exercise Troi has Barclay do in her office merely brings on a panic attack, forcing him to flee to the Holodeck to head it off.

The Holodeck seems like a perfect entertainment for a perfect society, an ideal addition to Gene Roddenberry’s utopian vision of the future. But like all technologies, it creates as many problems as it solves. And those problems are more than just the “trapped on the Holodeck” plot devices or deus ex machinae to fill episodes. In a universe where Holodecks are possible, what kind of cultural understanding of “reality” must be necessary in order for society to keep functioning? What kind of discipline, of binary “real” vs “fiction” worldviews must citizens of the Federation be raised with? And what happens to people like Barclay when that conditioning doesn’t quite take?

“You could write the book on holodiction,” LaForge tells Barclay. It’s a fairly straightforward line, meant to convey LaForge’s attempts at camaraderie and humor while also expressing his lingering reservations about Barclay’s weird habits. But to me it’s also one of the most incredible, the most blindly optimistic lines in all of Star Trek. Because, come on, Geordi. Is there really no book on holodiction yet?

———

Jill Scharr could write the book on holodiction. Follow her on Twitter at @JillScharr or read her other stuff at JillianScharr.WordPress.com.