Looking Glass Monsters

Once, when I was in high school, my English teacher took a moment out of her lessons to compliment me on my attire. “That is a lovely shirt,” she said, stepping closer to me. “What are those? Strawberries?”

When she moved closer to me she gasped. My button-down shirt looked like it was a lovely, dark paisley from afar, but upon inspection it became clear that the chaotic whorls and patterns were made of bones – like the floor of a charnel house littered with the remains of the dead. I didn’t wear the shirt because I was an aficionado of mass graves or a proponent of murder, but because I appreciated art that provoked – it is the jolt that wakes a sleepwalker.

[pullquote]I appreciated art that provoked – it is the jolt that wakes a sleepwalker.[/pullquote]

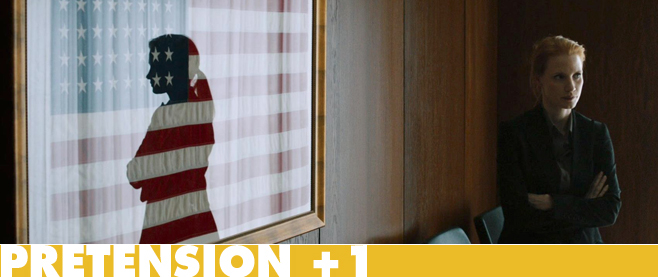

It seems like a no-brainer, but the fact that director Kathryn Bigelow was recently forced to reiterate the remedial lesson, “depiction does not equal endorsement” in a defense of Zero Dark Thirty is more than a little distressing to me. Her three-hour procedural thriller about the hunt for Osama Bin Laden opens on graphic depictions of waterboarding and other forms of torture that would be unbelievable if we didn’t already know that precisely the same kind of inhuman treatment occurred in places like Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib. I suppose people are upset that Bigelow had the gall to portray her protagonist as privy and participant to those awful acts of torture and still succeed in the end. The CIA, with the help of a crack squad of soldiers, eventually got their man. That, somehow, makes this often-ugly movie some kind of pro-torture propaganda.

When watching the movie’s tense conclusion depicting the orderly raid of Osama Bin Laden’s Abbottabad compound, I found myself wishing that modern military shooters were better at depicting not just the quiet, breathless tension of such operations, but also the harsher realities. The actions of these highly-trained soldiers weren’t accompanied by a swelling soundtrack by Hans Zimmer or even the high-adrenaline riffs of AC/DC. In fact, one of the movie’s rare jokes finds a soldier getting his mind right in the helicopter on the way to Pakistan. One of his comrades asks him what he’s listening to and he replies, “Tony Robbins.” Then these men, efficiently infiltrate our enemy’s stronghold, a place where women and children seem to outnumber AK-47s, and proceed to put down our foes in front of those innocent eyes.

I can’t say which I find more insulting – the notion that someone could misinterpret such a scene as tacit approval or the idea that a good part of the population is too dense to sort the right and wrong out of such a murky mess of bloody hands and necessary outcome.

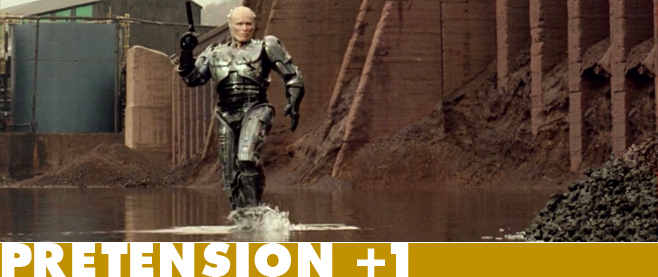

Bigelow’s biggest crime isn’t in misrepresenting the facts (which she is, we should remember, not required to adhere to in any reasonable fashion as a purveyor of fictionalized reenactments) but rather breaking the rules of easy-to-digest entertainment. These unwritten rules, ghosts of past censorships like the Hays code, require that evil deeds only be committed by sneering villains. And those deeds must go punished in the end. Clean-cut cops must take the criminal away in cuffs so the monster can stand trial.

Any adult knows that such a scenario is pure fantasy. Villains don’t always pay for their crime and great horrors are often committed by seemingly normal people – often by the people we task with protecting us. If Hollywood is guilty of producing pro-war propaganda, it’s best to look back to our whitewash of World War II, which depicts American G.I.s as the only military force in the history of the world to win a war without committing some kind of atrocity. And that’s not to mention the still-popular tradition of depicting the fascists from Hitler all the way down to the lowliest foot soldier as pallid ghouls, clearly separate from the mainstream of humanity. The sad, and terrifying, fact is that each war criminal and killer is a human being just like us, wrung through a machine of fear and lies that unleashed the monster that lives inside us all.

that such a scenario is pure fantasy. Villains don’t always pay for their crime and great horrors are often committed by seemingly normal people – often by the people we task with protecting us. If Hollywood is guilty of producing pro-war propaganda, it’s best to look back to our whitewash of World War II, which depicts American G.I.s as the only military force in the history of the world to win a war without committing some kind of atrocity. And that’s not to mention the still-popular tradition of depicting the fascists from Hitler all the way down to the lowliest foot soldier as pallid ghouls, clearly separate from the mainstream of humanity. The sad, and terrifying, fact is that each war criminal and killer is a human being just like us, wrung through a machine of fear and lies that unleashed the monster that lives inside us all.

That is why so many cringe at the ugliest of art. The paintings of Francisco De Goya, the lurid morality tales of EC comics, the leering sexuality of Lollipop Chainsaw and the bloody revenge of Quentin Tarantino movies are all mirrors reflecting the world we have made back at us. Some are more exploitative and twist the images like a fun house mirror, but the end effect is the same. They are meant to revolt, to throw cold water against our faces and remind us that world is full of horrors. Over and over we mistake art, our precious mirror, as the conveyance of evil. And, much like the dog in Aesop’s fable, we lash out at our reflection. Rather than merely lose a meal to avarice we risk marring our greatest gift, a clear glass that grants us the ability to peer into our own black hearts and name every evil we find there.

———

Pretension +1 is a weekly column about the intersections of life, culture and videogames. Follow Gus Mastrapa on Twitter @Triphibian.