Fine-Tuned Play

At the Game Masters exhibition, the most undoubtedly fascinating game was Asteroids. I’ve played Asteroids before in one form or another throughout the years, but never on the original, vector-based arcade cabinet. It’s hard to find the words for exactly what is so mesmerizing about the experience. Simon Parkin recently described it to me on Twitter as “a laser beam of wonder beamed directly from some unknown future” and I think that about nails it.

It’s like you aren’t just looking at some pixels on a monitor. You are watching a laser burn an image onto the underside of the glass – the ship and its bullets and the asteroids are being beamed out of an arcane machine right into your mind. It’s amazing.

[pullquote]When my brothers and I were kids, our house only had a single TV. This greatly limited the time we could spend playing the Super Nintendo.[/pullquote]

I don’t really know exactly how vector graphics work, but the arcade cabinet of Asteroids draws attention to its own material existence, to the machinations that burn the image onto the glass and onto your eyes. As you move the ship across the screen, ghosts of the past stay on the screen, fading after a few seconds, snaking a trail across the screen, again reminding you that you aren’t just looking at pixels on a screen, but an actual thing that was constructed for you, a combination of light that actually existed for a split second before gradually disappearing into oblivion.

It got me thinking about how I’ve never really thought about the physical materiality of a videogame that brings the images I engage with to life. I’ve never really ‘interacted’ with a videogame on that level of intimacy before.

Except, I kind of have.

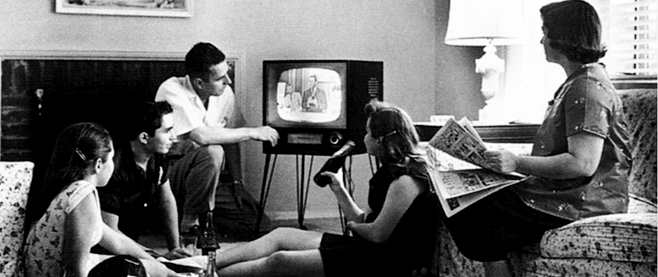

When my brothers and I were kids, our house only had a single TV. This greatly limited the time we could spend playing the Super Nintendo. Our parents would want the TV at night during the workweek and Dad would want it on weekends to either watch car racing or cricket. In hindsight, this is fair enough considering it was their TV, but as a kid it was so frustrating. I wanted to play videogames and I rarely ever could!

Then, one day, we were going through all the trash in the garage and we found our parents’ old television set. It was old before I even existed. It had those clunky knobs for VHF and UHF and this weird button/dial that you pushed in or pulled out to turn the TV on or off, and turned to raise and lower volume. Hidden behind a fake-wood compartment door that was always falling off were more knobs for brightness, contrast and color. It had that fake-wood chipboard frame that I think everything had in the ’80s and a pair of bug-like antennae that were rusted into the RF port.

Then, one day, we were going through all the trash in the garage and we found our parents’ old television set. It was old before I even existed. It had those clunky knobs for VHF and UHF and this weird button/dial that you pushed in or pulled out to turn the TV on or off, and turned to raise and lower volume. Hidden behind a fake-wood compartment door that was always falling off were more knobs for brightness, contrast and color. It had that fake-wood chipboard frame that I think everything had in the ’80s and a pair of bug-like antennae that were rusted into the RF port.

We got the antennae out of the RF port and managed to kind of get the Super Nintendo working on it. Kind of. It would always be noisy and fuzzy and crazy and distorted – and we could never quite find the right channel for it to actually work. When we found a channel that we could at least kind of play on (which is like finding a blizzard you can kind of drive through), it would only last a while before one of the knobs slipped, the image started rolling down the screen like a tape of film and we would have to fine-tune it again.

After a while, we realized that even if we couldn’t get exactly the right channel, we could fiddle with the brightness, contrast and color knobs to make the image more visible – or at least, the blizzard less visible.

This distortion and fuzziness became part of the experience of the SNES games we played at that time. The colors were always blurred and bright and diluted and weird. Like playing through some kind of water-paint filter, but it was better than not playing at all. For Donkey Kong Country, we would play in monochrome when the TV got too fuzzy. At other times the contrast would be so high as to transform the banana bunches into blobs of distorted yellow.

The one multiplayer game we owned on the Super Nintendo was Mortal Kombat 3, and we would spend hour after hour tearing each other’s spines out through our throats. While trying to stabilize the image one day, we figured out that by twisting the knobs in certain ways, we could make the blue health bars in Mortal Kombat 3 longer and shorter, making one player’s health stick out unnaturally from the white rectangular border meant to enclose it. We started to use this to give ourselves different handicaps. You were allowed to play as Motaro, the overpowered centaur, for instance, only if the TV was tweaked so the other player had more health. What started as desperation and experimenting had evolved into intentional gameplay tweaking.

The one multiplayer game we owned on the Super Nintendo was Mortal Kombat 3, and we would spend hour after hour tearing each other’s spines out through our throats. While trying to stabilize the image one day, we figured out that by twisting the knobs in certain ways, we could make the blue health bars in Mortal Kombat 3 longer and shorter, making one player’s health stick out unnaturally from the white rectangular border meant to enclose it. We started to use this to give ourselves different handicaps. You were allowed to play as Motaro, the overpowered centaur, for instance, only if the TV was tweaked so the other player had more health. What started as desperation and experimenting had evolved into intentional gameplay tweaking.

By playing with the TV itself, we changed the experience of the game. Did it actually do anything? Looking back, probably not. But as kids, it truly felt like it made a difference. It felt like we were interacting and altering the game on some base, material level that you never could just by pressing buttons on a controller.

These days (even in those days, really) videogames try their hardest to hide their own material existence. They want us to be ‘fully immersed’ in their worlds and to forget about their technological realities. They don’t want us to think about the television boxes we are looking at and engaging with. But sometimes, drawing attention to these material objects sharing the same actual space with you can be fascinating in its own right. When the Asteroids arcade cabinet burned lasers across the screen, when my brothers and I tweaked knobs to gain more health in Mortal Kombat 3, when Hideo Kojima tries to psyche me out in Metal Gear Solid by blacking out the screen and writing HIDEO in green chunky letters in the corner, we aren’t just playing with videogames, we are playing with TVs, and the TVs are playing with us.

———

Follow Brendan on Twitter @BRKeogh.