TV is the Government: The Underground Vaudeville of TV Party

Not always, actually quite seldom, is the distinction between art and absurdity a relevant one. It certainly doesn’t matter when in a TV show you combine live music, in-studio party, fancy dress, videotapes, punk, disco, anarchism, new wave, visual arts, rap, interviews, phone-in sessions, shaky camera angles, crude advertising and live drug taking. All this featuring guests such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, John Lurie, David Byrne, George Clinton, Fab Five Freddy, Tuxedo Moon, Debbie Harry, Maripol, Iggy Pop, Chris Burden and John Feckner, just to name a few. The uniqueness of TV Party, however, was not as a celebration of the apotheosis of the underground, but that this played out on the mass media it rebelled against.

[pullquote]The cocktail party which could be a political party.[/pullquote]

On air for one hour every Tuesday night, from 1978 to 1982, TV Party was a piece of DIY experimental broadcasting hosted and conceived by Glenn O’Brien. It pioneered an alternative use of the medium, breaking its rules by looking deliberately amateur and shattering the traditional distinction between the audience and the entertainers through the format of the party.This was made possible by the establishment of public-access television between 1969 and 1971. Created by the Federal Communications Commission, public access allowed ordinary people to freely create and broadcast TV programming.

With Warhol’s Factory as a background, a role as editor for Interview, Rolling Stone and High Times and the cream of New York hip music scene as best friends, O’Brien embodied the purest archetype of coolness (and he still is, considering in 2009 he was named one of Top 10 Most Stylish Men in America by GQ Magazine). His inspiration for the show came from Hugh Hefner’s programs of the Sixties: Playboy’s Penthouse and Playboy After Dark, also based on the format of the cocktail party. Improvisation was the only rule: the team would meet in a bar shortly before they went live, and everything was unplanned, with the exception of the themed episodes, which involved costumes and more preparation.

Warhol’s influence seems evident in Glenn’s fascination with mass culture and mass communication. However, instead of the glossy neutrality pursued by his mentor, he credited his project with a (half satirical) political value. “The cocktail party which could be a political party” was the way he introduced each episode of the show, aware of the more brainwashing-like role that TV was gaining in  the Reagan era: “In America, TV is the form of government. Nothing can be governed but people and TV has proved to be the greatest modern instrument for their control. TV PARTY presents and reveals ENTERTAINMENT as the ACTUAL form of GOVERNMENT.” (Glenn O’Brien, TV Party Manifesto, published on Bomb magazine, 1981.)

the Reagan era: “In America, TV is the form of government. Nothing can be governed but people and TV has proved to be the greatest modern instrument for their control. TV PARTY presents and reveals ENTERTAINMENT as the ACTUAL form of GOVERNMENT.” (Glenn O’Brien, TV Party Manifesto, published on Bomb magazine, 1981.)

The TV Party gang even tried to run in the 1981 New York City Elections (With O’Brien as a candidate for mayor), but they didn’t get enough signatures to make it on the ballot. Their manifesto presented the party as a forum and model for social and political interaction and matched the most radical and clever foolishness with seminal ideas about the value of local culture, public access to information, the manipulating effect of communications monopolies and dull mainstream entertainment, and the proposal of broadcasting every government process making meetings or court sessions available to everyone.

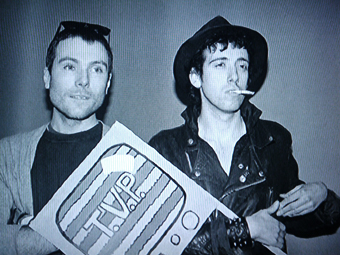

The TV Party gang was basically recruited among O’Brien’s buddies. Blondie guitarist Chris Stein was the co-host, photographer Edo Bertoglio was the cameraman and niche film auteur Amos Poe contributed with his chaotic and epileptic (depending on the level of his intoxication) direction, careless of technical inadequacy or broken microphones, often choosing to frame almost randomly; think feet or somebody who wasn’t talking. A regular presence in the show was the TV Party Orchestra, whose leader was violinist Walter Steding, who Glenn met at the Factory, where the musician was working as Warhol’s painting assistant. Walter brought in the other orchestra member Lenny Ferrari. Lenny was a drummer, but because the studios didn’t allow real drums, he invented a drum kit consisting of a music stand, small cymbals and the New Yorker Magazine.

[pullquote]Niche film auteur Amos Poe contributed with his chaotic and epileptic (depending on the level of his intoxication) direction.[/pullquote]

Today, 30 years later, TV remains the major entertainer for much of the world population and a critical filter of information. But with hundreds of cable channels available along with the possibilities offered by the web, things are a lot different and the potential for niche, alternative programming is now huge. So is the competition, a development that hasn’t freed TV from advertising, which is perhaps playing an even bigger role now than in the past decades.

TV Party started selling ads to clubs, small record companies and obscure bookstores only after moving into color, which was obviously much more expensive than the black and white. It didn’t work really well though, with O’Brien ending up very often making fun of the advertiser.

The end of the show, however, came almost spontaneously, with the dispersion of the crew: Chris Stein got seriously ill, Blondie broke up, Lenny Ferrari started touring with Lou Reed, Walter Steding was mainly focusing on his own band and Glenn O’Brien got married and started performing as a comedian. That’s more or less what happens when you turn 30: you don’t know where your friends have gone, and you realize it’s time to do something different.

This story originally appeared on Network Awesome and is reprinted here in a slightly edited form with their kind permission. The author, Gabriella Arrigoni, is an independent curator and writer; former editor in chief of UnDo.Net, she now contributes to a number of contemporary art magazine. She lives in Newcastle upon Tyne (UK) where she also works as translator. She is part of the collective Nopasswd in[ter]dependent contemporary culture.