I Don’t Believe in the No-Win Scenario

The crew of the U.S.S. Enterprise is dead.

Sulu is the first to die, hurled from his seat at the helm when the Klingon torpedo hits. Uhura slumps over her console, which has just exploded in a shower of sparks. Dr. McCoy is killed by another blast as he hurries to attend to Sulu. Spock has just had time to announce, “No power to the weapons, Captain,” before shrapnel spears him in the back and he collapses to the deck.

“All right, open her up,” says a voice from off-screen, and a massive cargo door opens. A figure emerges from the bluish smoke of the destroyed bridge.

“Any suggestions, Admiral?” asks the Captain.

“Prayer, Mr. Saavik,” says James T. Kirk. “The Klingons don’t take prisoners.”

———

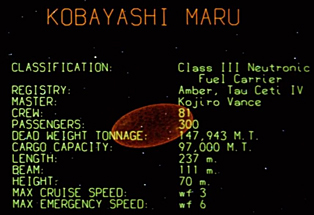

The opening scene of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan is memorable enough to warrant its own Wikipedia page. The sequence depicts the Kobayashi Maru simulation, a test given to all Starfleet command cadets. Patrolling the Neutral Zone, a space DMZ between the Federation and the hostile Klingon Empire, the cadet’s starship receives a distress call from the civilian vessel Kobayashi Maru. Disabled by a “gravitic mine,” the Kobayashi Maru is rapidly losing hull integrity and life support. All 381 souls on board will die if help doesn’t arrive soon. But there’s one problem: the Kobayashi Maru has drifted into the Neutral Zone and the cadet’s starship is the only vessel that can get there in time. Now the cadet must decide: save the civilians and risk all-out war, or abandon them to die in enemy space.

The opening scene of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan is memorable enough to warrant its own Wikipedia page. The sequence depicts the Kobayashi Maru simulation, a test given to all Starfleet command cadets. Patrolling the Neutral Zone, a space DMZ between the Federation and the hostile Klingon Empire, the cadet’s starship receives a distress call from the civilian vessel Kobayashi Maru. Disabled by a “gravitic mine,” the Kobayashi Maru is rapidly losing hull integrity and life support. All 381 souls on board will die if help doesn’t arrive soon. But there’s one problem: the Kobayashi Maru has drifted into the Neutral Zone and the cadet’s starship is the only vessel that can get there in time. Now the cadet must decide: save the civilians and risk all-out war, or abandon them to die in enemy space.

But the test is rigged. Proceed into the Neutral Zone and you’re set upon by Klingon warships who blast you out of the stars. They won’t negotiate, they won’t retreat and they won’t die. Victory, military or diplomatic, is impossible. If you’re lucky, your escape pods will make it away safely before your warp drive explodes. If not, everyone on your ship will die along with the civilians on board the Kobayashi Maru.

Of course, the choice isn’t really a choice at all, is it? It’s not stated in the movie, but it’s probably safe to assume abandoning the Kobayashi Maru results in failure too — and perhaps an even less dignified one at that. No starship captain worth his stripes could live with himself if he’d done nothing.

So the game is rigged on two levels. Choose to play, and you lose. Choose not to play, and you still lose.

———

Given permission to speak candidly, Saavik confronts Kirk. “I don’t believe this was a fair test of my command abilities,” she protests.

“And why not?” Kirk replies.

“Because there was no way to win.”

“A no-win situation is a possibility every commander may face,” Kirk says, circling her. “Has that never occurred to you?”

“No, sir, it has not.”

“How we deal with death is at least as important as how we deal with life,” Kirk says, “wouldn’t you say?”

———

There are two reasons this exchange is a beautiful capstone to the movie’s opening scene.

The first is that we will indeed get to see how Kirk deals with death. At the end of the film, Spock sacrifices himself to save the Enterprise, rushing into a radiation-filled chamber to fix the warp drive and enable the ship’s escape from Khan’s exploding vessel. Separated by a transparent wall, Kirk paws futilely at the glass as he watches his best friend die. This is Kirk’s no-win scenario: for once in his long and brilliant career, he is unable to cheat death. He collapses to the deck, his back to the glass, Spock in a mirrored position on the other side. Kirk’s face is paralyzed with shock and grief. For perhaps the first time in the history of the franchise, we see Kirk utterly broken, utterly lost. It’s a visually powerful return to his final line of that opening scene.

The first is that we will indeed get to see how Kirk deals with death. At the end of the film, Spock sacrifices himself to save the Enterprise, rushing into a radiation-filled chamber to fix the warp drive and enable the ship’s escape from Khan’s exploding vessel. Separated by a transparent wall, Kirk paws futilely at the glass as he watches his best friend die. This is Kirk’s no-win scenario: for once in his long and brilliant career, he is unable to cheat death. He collapses to the deck, his back to the glass, Spock in a mirrored position on the other side. Kirk’s face is paralyzed with shock and grief. For perhaps the first time in the history of the franchise, we see Kirk utterly broken, utterly lost. It’s a visually powerful return to his final line of that opening scene.

But Kirk’s opening exchange with Saavik is also notable for its irony. In the middle of the film, Kirk, Saavik and McCoy are stuck on Regula I with Kirk’s ex-flame Carol Marcus and their son David, both of whom developed the life-creating Genesis Device. Khan has abandoned them on a lifeless moon, just as Kirk marooned him on the wasteland world of Ceti Alpha V decades ago. He’s also stolen Genesis, which he intends to use as a planet-killing weapon. The Enterprise is not answering hails and may be dead in space or even destroyed. The situation could not get much more hopeless.

It’s then that Carol escorts Kirk to the Genesis Cave, a massive underground chamber where she’s test-deployed the Genesis Device. A verdant forest stretches out for miles beneath an artificial sun. Though it’s just a matte painting, it’s hard to discount the beauty of the vista. Life is thriving in this desolate place; fruits and vegetables even grow in the valley below. If they are to be marooned here, at least they will have enough to eat. Perhaps there is a glimmer of hope after all.

Sensing this, Saavik chooses this moment to ask Kirk how he beat the Kobayashi Maru test. Between bites of an apple, Kirk reveals that he reprogrammed the simulator so it was possible to win. Kirk was the only cadet to beat the no-win scenario, McCoy says.

“He cheated,” scoffs David.

“I changed the conditions of the test,” Kirk retorts. “Got a commendation for original thinking. I don’t like to lose.”

“Then you never faced that situation,” Saavik says. “Faced death.”

“I don’t believe in the no-win scenario,” Kirk says. “As your teacher, Mr. Spock, is fond of saying, I like to think there always are…possibilities.”

So we see that Kirk’s earlier reply to Saavik — his implication that the test is not meant to measure the cadet’s ability to rescue the civilians, but to assess the cadet’s composure in the face of certain death — is both a sincere defense of the test’s lesson and a winking acknowledgement of its failure. Kirk is not interested in measuring his performance as he fails to do the impossible. His goal is making the impossible possible.

———

But there’s another reason the Kobayashi Maru test is so interesting: the concept itself.

The no-win scenario is not a fun thing to contemplate. We don’t like games we can’t win. Faced with impossible scenarios, we often shut down, retreating into despair, or denial or detachment. We don’t even like to think about games we can’t win: it’s an exercise in frustration, exposing our powerlessness, our smallness, our mortality. Life is, of course, the ultimate no-win scenario. The ending is the same for everyone.

[pullquote]They’re growing up facing a test that is rigged against them[/pullquote]

Some might argue God is our way of cheating that test.

It’s rare to see this kind of heady concept explored in an action movie. But that’s what Star Trek has always done best. It’s never been afraid to wade into complex ideas, even if it often did so with a healthy dose of camp. Encasing them in an entertaining sci-fi wrapper made those concepts more palatable.

J.J. Abrams’ 2009 reboot of Star Trek is more direct about the lesson of the Kobayashi Maru test. “The purpose is to experience fear,” Spock explains. “Fear in the face of certain death. To accept that fear and maintain control of oneself and one’s crew.”

In other words, the test is this: can you gaze into the abyss and not let it gaze into you?

———

For practical reasons if not philosophical ones, we have to confront no-win situations all the time. Someone has to think about the worst-case scenarios so we can prevent them. Andrew Bird captures this tension in his song “Fiery Crash,” which portrays the anxiety of passengers waiting to board an airplane that could very easily plummet to the earth in flames. It’s an acknowledgment of the emotional toll thinking of the worst can take on a person. (Consider Edward Norton’s accident assessor in Fight Club, whose job is to visit horrific scenes of mutilation and determine the precise cash settlement his insurance company will pay out.) “To save all our lives / you’ve got to envision / the fiery crash,” Bird sings, as if addressing the engineers who design aircraft, the pilots who operate them and the maintenance crews who keep them safe. Even something as commonplace as air travel is, as Bird sings, “a nod to mortality.”

———

It’s easy to forget that some of us face the Kobayashi Maru test every day.

I don’t often talk about my job, but I’m proud of what we do. My small nonprofit brings community and corporate volunteers into classrooms all across the Boston Public Schools to mentor and tutor kids. We’ve been around a long time. So have the problems.

Of the 57,000 students in the district, over 40% do not speak English as their first language. Nearly 80% of them are eligible for free or reduced-price lunches, a common indicator of poverty. Although the graduation rate has improved significantly in the last few years, more than 35% of BPS students do not complete high school in four years. Standardized test scores lag behind the rest of the state, often by double-digit margins, and schools are under constant pressure to increase results even as their resources are being taken away.

One of our students told his mentor earlier this year that he felt uncomfortable at home. His mother would have strange men coming to their apartment at all hours of the night. One time one of them had a pistol.

The student was in first grade.

It’s not hard to understand why some of our kids feel like they’re constantly facing a no-win scenario. They’re growing up with violence, with drugs, with racism, with poverty. They’re growing up with families struggling to make ends meet, sometimes thousands of miles from where they were born, without college degrees or even basic proficiency in the English language. They’re growing up playing parent for their younger siblings because their actual parents are working three minimum-wage jobs just to get by. They’re growing up surrounded by temptations to take the easy way with drugs, with gangs. They’re growing up in schools that are compelled to test them and test them and test them without desperately needed resources and funding. They’re growing up in a media environment saturated with negative stories about what miserable failures they are.

It’s not hard to understand why some of our kids feel like they’re constantly facing a no-win scenario. They’re growing up with violence, with drugs, with racism, with poverty. They’re growing up with families struggling to make ends meet, sometimes thousands of miles from where they were born, without college degrees or even basic proficiency in the English language. They’re growing up playing parent for their younger siblings because their actual parents are working three minimum-wage jobs just to get by. They’re growing up surrounded by temptations to take the easy way with drugs, with gangs. They’re growing up in schools that are compelled to test them and test them and test them without desperately needed resources and funding. They’re growing up in a media environment saturated with negative stories about what miserable failures they are.

They’re growing up facing a test that is rigged against them.

And yet, as Spock says: there always are possibilities.

What you don’t see enough in the news is how the kids, like Kirk, change the conditions of the test. You don’t see enough stories about the high schoolers who arrive in this country only knowing how to say “hello” and “thank you” and end up, after intense study, with free rides to state universities. You don’t see enough stories about eighth-graders who have made that crucial decision to get a diploma instead of a gun. You don’t see enough stories about the elementary school children whose faces light up when they get a new book.

You don’t see them believe they can make it. But they do.

They don’t believe in the no-win scenario.

And if they don’t, why should I?

———

JPG may believe in the children of Boston full-time, but he mostly tweets about Star Trek and videogames. Follow him @JohnPeterGrant.