Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest

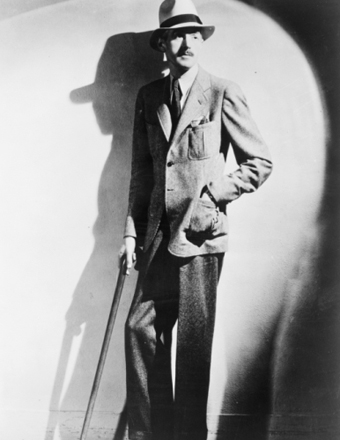

Welcome to our new pulp book club – and boy, do we have some back room roscoes to investigate, some broads to pitch woo with and some tiger milk to put down. Confused? You won’t be soon. Get three fingers of that Jameson and light that cigarette with a match on your stubble (ladies, on the leg stubble will do). We are about to go deep, deep into the murky dark, my friends. And to do that, we’ll start at the Black Mask beginning with a little Dashiell Hammett, who first made the hardboiled genre popular with violence, uncompromising characters and the dark shadows of male libido.

Hardboiled godfather Dashiell Hammett’s work is the “epitome of good taste” compared to today’s hardboiled stories, according to noir aficionado Woody Haut. That might seem like a sharp slap across the face considering the usual shenanigans noirists aim to get up to, but without Hammett’s tight style, terse flâneur, and diabolical towns full of diabolical people, we wouldn’t have all the greatest hardboiled fiction of today. 1929’s Red Harvest is where it all began: literary critic André Gide wrote that it is the “last word in atrocity, cynicism and horror,” and Red Harvest‘s critique of company capitalism is still to this day second to none.

Hardboiled godfather Dashiell Hammett’s work is the “epitome of good taste” compared to today’s hardboiled stories, according to noir aficionado Woody Haut. That might seem like a sharp slap across the face considering the usual shenanigans noirists aim to get up to, but without Hammett’s tight style, terse flâneur, and diabolical towns full of diabolical people, we wouldn’t have all the greatest hardboiled fiction of today. 1929’s Red Harvest is where it all began: literary critic André Gide wrote that it is the “last word in atrocity, cynicism and horror,” and Red Harvest‘s critique of company capitalism is still to this day second to none.

Hammett’s credentials as a writer of detective fiction couldn’t be better: as an operative in the Pinkerton Detective Agency, his experiences directly informed his prose, which perhaps explains why Hammett writes with such economy and authority. Many consider Hammett’s torchbearer Raymond Chandler more of a romantic, more of a lyrical poet of California violence. Yet Red Harvest has its moments, my favorite among them: “I have walked as many streets as I did in my dreams.”

From the first moment Hickey Dewey calls Personville “Poisonville” and his shirt a “shoit,” you know you’re in for the ride of your life. Old Red Harvest gumshoe Brian Taylor and newbie to the book Editor in Chief Stu Horvath picked it up and shook the life out of it. Enjoy, and stick around for the discussion all week! There might be some chin music.

– Cara Ellison

———

One thing I like about the Op: He doesn’t know what he’s doing. There’s no sense with him, unlike, say, Poirot, that he’s one step ahead of everyone, playing a game with everyone involved and just waiting for the right moment to expose everyone’s crimes. He’s, well, not necessarily bumbling through his investigation. But he’s this violent force that’s messing with the corrupt system that is Poisonville and seeing how it responds to him. The town itself is self-contained and he is an outside agent (both in the detective agency sense and in the one who acts sense).

– Brian Taylor

———

[pullquote]I first heard Personville called Poisonville by a red-haired mucker named Hickey Dewey…He also called his shirt a shoit.[/pullquote]

The Op isn’t just violent, he’s honest too. There is only one time in the entire novel that I can recall him telling a bald-faced lie. Sure, he might not tell the whole story right away, especially if no one is asking, but he also doesn’t hesitate to tell these mugs – these bootleggers and gamblers and killers – the straight dope when it suits him. They don’t know how to deal with that – crooked is as crooked does – so they trust him to be as crooked as they are.

They return his honesty with candor and then they hate him for it when he uses it to destroy them. When the Op is worn out from all the death in town, he drunkenly rambles on about his desire to improvise weapons, not realizing that his deadliest one has been his straight-shooting mouth all along.

– Stu Horvath

———

I want to say it’s a particularly American worldview, this combination of violence and honesty. It’s not hard to see the Op as a kind of cowboy. Except where the latter’s violence is a mythic necessity for the establishment of society, the Op’s violence is there to purify society. There is lots of writing about the figure of the cowboy and Western fiction of the early 20th century, much of it about how the Western dealt with gender, women and civilization and religion versus, well, men.

Raymond Chandler’s Trouble is My Business was published about 20 years after Red Harvest. The introduction to this collection of Philip Marlowe stories could be a short essay on Hammett’s work versus the more British (well, and Poe-ish) detective story:

“The emotional basis of the standard detective story was and had always been that murder will out and justice will be done. Its technical basis was the relative insignificance of everything except the final denouement.”

Basically: nothing that happens REALLY matters until the end, when the detective explains everything that happened. When I studied detective fiction in undergrad, we talked about how there are two stories in this kind of detective novel: the story that you read and then the story of the crime as reconstructed by the detective. It’s not cut-and-dry, but you can be sure that, say, Holmes’ investigations are much, much different than the Op’s.

[pullquote]My God! For a fat, middle-aged, hard-boiled, pig-headed guy, you’ve got the vaguest way of doing things I ever heard of.[/pullquote]

Chandler presents the American detective story, the hardboiled story, as an inversion:

“…obviously it does not believe that murder will out and justice will be done – unless some very determined individual makes it his business to see that justice is done. The stories were about the men who made that happen.”

Determination: it’s not that the Op is some kind of genius (although he’s very, very good at his job). Readers don’t sit in awe of his powers of deduction, we ride along with him as he acts. Which is the other thing Chandler points about about the kind of detective story Red Harvest is: it’s not the end that matters, but what happens along the way. “When in doubt have a man come through a door with a gun in his hand,” Chandler writes. It’s like the Op’s philosophy as plot construction: just do something.

The triumph of honesty, determination and violence (ethically justifiable, obviously!). The importance of action over reflection. It doesn’t get much more American than that.

– BT

———

It is also very American that the Op is, by his own admission, about 20 pounds overweight.

But I’ve already covered the Op’s forthright honesty. Meanwhile, Brian just perfectly summed up the appeal of Red Harvest: we ride along with the Op as he acts and the main reason that works is Hammett’s writing. The language he uses, the way he constructs sentences and paragraphs – I am in awe of it. It is full of energy, relentlessly pushing forward at a breakneck pace, never a wasting word, always surgically precise.

This is the first book in ages that I have dog-eared pages because of a line that was worth remembering. Listen to some of these:

“Who shot him? I asked.

The grey man scratched the back of his neck and said: “Somebody with a gun.”

or

[pullquote]You’re drunk, and I’m drunk, and I’m just exactly drunk enough to tell you anything you want to know.[/pullquote]

“There’s no sense in a man picking out the worst name he can find for everything.”

or

I don’t like being manhandled, even by young women who look like something out of mythology when they’re steamed up.

or

I turned to Reno and asked: “Isn’t that it?”

He looked at me woodenly and said:

“You’re telling it.”

I continued telling it.

That last one is particularly great. There’s no real description of the scene or the men talking, just the rhythm of the words and the line breaks to tell you everything you need to know about their expressions and their tone. There is no room for nonsense there, not for Hammett, not for the reader and, most of all, not for the Op.

– SH

———

I think you’ve got the essence of why, for me, hardboiled is such a great genre. It is terse and about action and reaction: mouths are for kissing and punching, not talking, and when talking is done from the Op it’s straight and deadly. I think it’s interesting that Brian brings up the American cowboy in reference to this, as there are many  hardboiled heroes who are essentially lone cowboys, limping through the saloon doors brandishing a gun to put things right. This genre is responsible for a lot of the American action heroes we see today and I think that is one reason why it’s so important.

hardboiled heroes who are essentially lone cowboys, limping through the saloon doors brandishing a gun to put things right. This genre is responsible for a lot of the American action heroes we see today and I think that is one reason why it’s so important.

However, as we go along these mean streets into the depths of the murky hardboiled psyche, I’d like you to see what people outside of the United States have done with the hardboiled hero – this is not strictly an All-American thing that Hammett has started. There’s such a thing as the Tartan Noir movement (from my home country, Scotland) and there’s a decent amount of Irish hardboiled novels too. Even the masculinity that the Op displays here has been subverted by female hardboiled detectives: Sara Paretsky’s V.I. Warshawski (ignore the film completely) is the toughest karate black belt badass I’ve ever read about – she’s constantly in a hospital bed, being fixed up for the next fight.

It might also be interesting in the discussion to think about the politics of this genre. This book’s title, retrospectively at least, seems politically provocative, and it’s also interesting to note that in the 1950s, Hammett’s support of leftist causes had him hauled up before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Hammett refused to give names. His books were removed from libraries as a result. Is there a left-lean in Red Harvest? Is the Continental Op a bleeding heart, as well as a bleeding everything else? Does that imbue the hardboiled genre with a working man’s ethic?

I’ll leave you to discuss. Happy hunting, ya bunch of animals.

– CE