A Dialogue with Grace Benfell

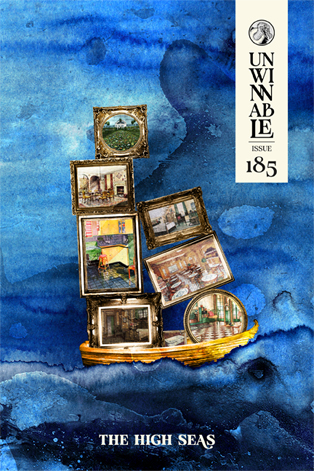

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #185. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

The art of games criticism.

———

Grace Benfell is a writer based in Chicago. She is the author of Killing Our Gods, out later this year, and the co-editor of TIER, a journal for criticism on obscure games. Grace’s essay on horny games was February’s criticism of the moment, which is exceptional for an argument so counter to the critical and popular consensus. We talk about the troubles of online, structural problems to writing good crit and going long.

Autumn Wright: I want to talk about what prompts a criticism like this: How you come to your thesis, what the exigence for publishing an essay like this is, the motivation behind the work?

Grace Benfell: Unfortunately, perhaps in this case, it was mostly me being mad at posts. I talk about this in that essay, but since 2020 (and Hades and Baldur’s Gate 3 in particular) there were people saying Oh, this is so cool and good horny. And then playing these games, I was like, I just don’t feel like this is meaningfully erotic, like at all, or only in individual moments. I think this is also just in culture generally, like there was that Good Place photo shoot of people being like My sexuality is this photo shoot. And then quote tweets of them like My sexuality is hot people. And none of this really matters, but I felt that that’s worked in tandem with this general cultural moment of prudishness that we’re living through. The way that we respond to stuff that is ultimately tamer than your average ’90s erotic thriller as being this revelatory work about sex, I feel like that is reflective of something deeper.

So, it was thoughts that I kept having and wouldn’t go away. That led me to the place where I wanted to write and get some of that on paper, and also where I knew that I was speaking to something real, because it kept coming back. I think it’s easy, especially as a writer who works a lot online, to get mad about something disproportionately. People are always saying very dramatic things about things people say online, which, to me, are not very illustrative of anything. So, it came from a place where I knew I was speaking to something real and that I had something to say about it.

Across your bibliography you use a lot of citations, which is itself rare in games writing, but you also cite the writing that’s constructed the paradigm you identify – that these games are or aren’t horny, that Final Fantasy VII Remake is subversive of gender norms, etc. – and go so far as to rebuke them. Seeing such critical dissent is rare in games media.

It’s a real problem that we have. To some degree it comes from maybe not a good place, but understandable place that Gamergate won. Anyone who is writing online – especially women and even more especially queer women – are living in the shadow of that reality that anything they say could be subject to the most vile and out of pocket harassment. I’ve been fortunate. I think I play too inside baseball maybe, I really haven’t gotten it that much, and so maybe that’s enabled me to do this a little bit more. But I think that criticism is dialogue. And even if your only citation is the game itself, you’re still talking to a thing that’s separate from you and that feels important to me. That’s the heart of the thing, that you are having a discussion with something. That means taking it seriously in a real way.

I don’t know when I rebuke someone that it’s complimentary, exactly, but it means that I’m having to engage with the ideas and I’m taking them to a certain degree of seriousness. You have to do that to write good crit. It’s fundamental to it. I don’t really know how else I would do that. I value doing this well and, to me, you have to engage with the counter argument to do it well. I’m not really about subtweeting, or at least I’m not now, maybe I used to be, but I’ve outgrown it.

Subtweets are a great outline for a blog or an essay, I’ve discovered. You have to critically engage with a videogame or whatever you’re covering and then also the blogosphere, the mediascape, tweets. Do you ever struggle with taking those things seriously when the world is what it is?

That’s a good question, and I try to be careful now (not that I always succeed) to not get too heated about posts in particular, because I think a fundamental thing that people do when they get upset about things people say on the internet is as an unfair extrapolation. I’ve seen a lot of people lately online be mad at a hypothetical voter who abstained from voting for [Kamala Harris], for example. Be furious with this person that they just kind of imagined in their head that doesn’t really exist and that is representative of things they’ve seen people say, but not really representative of things people have done. The people who I saw most vigorously advocating for abstaining were people for whom a Trump presidency was deeply risky and scary, but who nevertheless had this sincere and powerful moral conviction against voting for [Biden] and voting for Kamala.

I try not to take things too seriously, but also anything someone puts in the world, anything someone makes is an act of, if not love, then at least respect, to take something and consider it worthy of being analyzed. It is important to respect these things because the stuff we make and the things we say, they do shape our world, or they shape the world that might be in the future, and that is a cause-and-effect process that’s hard to mark but that you can see. There are so many atrocities and so many good things. There were hypotheticals and ideas before they ever became real, were written about before they became real. That is a reality that also has to be taken seriously, and there has to be a response to what is created.

The idea that to do criticism is to show love and care to whatever you’re criticizing is something that a lot of writers in our field hold, but I’ve noticed when it comes to turning that attention to writing, people are much more apprehensive to take that in the good faith that you’re trying to.

It happens so fast that, good faith or bad faith, criticism of things people say or things people write get equated to Gamergate. And it becomes very difficult to critique the writing of marginalized people, even writing that is obviously well-intentioned, because any criticism of it is so immediately equated, but this is used by bad actors all the time to cover for themselves. I’m thinking about the Lockheed Martin trans person who was constantly like I’m just little and I can’t do anything bad. Meanwhile, they’re working for one of the most evil companies in existence.

So much of the rhetorical room we take up is dealing with hypothetical, like Might I resemble something that is bad or might this be something someone on the right would do? We have to start having our own standards and not letting them fucking dictate what is right and good. We have to start shaping the conversation ourselves. Games crit, in a foundational way, is reactionary. It really lets bad actors dictate the kind of conversations we have. And I just don’t want to do that anymore.

Speaking of criticism of criticism, you wrote what I felt was the definitive review of Critical Hits last year. Rereading it today I felt like a lot of what you said was as indicting of the games media as the editors in the literary world completely ignoring the work critics like you make.

That was really the thing that struck me so much reading Critical Hits. This is just the same. You could read everything that shows up on any average week of Critical Distance and have a pretty similar hit rate of actually good shit to that book. And a lot of the same problems exist because this is a field where it’s so hard to maintain lessons and learn things and pass that on. Layoffs, burnout, there’s so much that has made that incredibly, incredibly difficult. So, it’s not really a wonder to me that a bunch of newcomers to this field create something that’s so similar, because these are problems that are omnipresent.

One of your points was about the games that are covered and how they are either recent, big, or indie darlings. Through your work, you have written a lot about indie games. I’m wondering if you think there’s some obligation or responsibility or some other word to describe the role of critics in talking about lesser-known works.

To some degree, none of this matters. I don’t mean to be too cynical about it, but I don’t know how much there is of a moral imperative. I do think it is generally a good rule that the most interesting stuff is happening in a margin somewhere and is difficult to find or track, and if you are a person who is genuinely interested in any medium – in music, in in film or in games – you are interested in what people are doing outside of established channels. Or not even necessarily completely outside, but in smaller avenues. Reading people’s chap books, reading stuff people self-publish. And I’m not always the best at doing this. I exist in in the culture as much as anybody else. I’ve been listening to a fuck ton of Kendrick Lamar over the past couple months because he keeps being in the public eye, so I keep thinking about him. And that’s just what it is like. I’m in it with everyone else.

I wrote a piece about Metroid for Gamespot a couple years ago. I’m very complimentary to the game and talk about how it’s very meaningful the way that game starts from, as far as a pixelated image on the NES can go, from a very naturalistic place that gradually becomes more machinic and more industrialized and how that’s cool. It’s visual storytelling. And there were people in the comments and even in my quote tweets that were basically like It’s not that deep. [Yelling] Yeah, nobody hates videogames more than gamers. People really do act like this is a medium that has no value at all. I see it all the time and I think this is very sad and very frustrating. This is worth taking seriously.

Because of that, I have this curiosity for what stuff that is not at the mainstream looks like. I want to know what’s going on there. And I’m not frankly the best at keeping up with it. I’m really not a very good like itch.io scroller, downloading new shit and trying it out and doing this stuff. I’m mostly playing AAA games in my free time or indie games with some level of backing. But some of my very favorite games are pretty small team stuff, the kind of stuff that we would cover on TIER. The good stuff is going to be there, and so you might as well try and find it if you care about this at all.

You also point out that much of the book is not actually criticism but personal essay and retrospective. Conflating these is something I’m also guilty of, but they seem to blend together within some writers and audiences.

I go back and forth on this because I do think that it can be very effective to write personally. I don’t think that that’s necessarily a weakness and there are a lot of writers that I really, really admire who can do that in really profound ways. I just think it’s tricky. I don’t mean to bemoan online so much, but I do think there is an egotism, an assumption that other people should care about your life. Maybe people should, but they don’t. You have to sell me on it. You have to do work to make me invest in what is happening. And that work is not even You have to appeal to this audience member, it’s deepening your relationship to yourself.

I recently read Jennette McCurdy memoir I’m Glad My Mom Died, which is astonishingly well-written in part because there’s a lack of reflection in it until the point where she can have the reflection back on her life. She doesn’t really opine about lessons she learned later until she reaches the point in the story where she’s learned it. Because of that, the emotions and the confusion and feelings that she had as a child who was abused by her mom in this incredibly difficult situation, being a child actor, that stuff had this emotional weight that is not undercut by Well eventually I knew better later. It just hangs there. And the other thing it’s really good at is it’s so funny and absurd and the heartbreak that you experience and the sensation of terror and loss is deepened through how funny it is. It doesn’t make you less empathetic to her and her situation. It deepens it. I think people are very afraid – and I am very afraid, I’m not immune to this at all – of people laughing at their lives. And I think when you write about something personal, you do want to find parts of it funny or find the absurdity in it, and if you can’t do that, maybe you shouldn’t be writing about that thing yet. That’s not a hard and fast rule, but like a rule of thumb, maybe. There’s an emotional depth that can come from a little distance that is so hard to scrounge for when you’re still processing something.

So much of online personal writing is about trying to write through it, which I don’t think is the kind of thing that you should show other people or that’s helpful for other people to read. And I’m, nobody’s priest. I can’t tell you what to do, but this is my feeling. I have also moved more and more away from personal essay as my career has gone on and I think part of it is feeling there are things I wrote, even things that I’m proud of and that I appreciate, that I know now I would approach differently and they would have more depth and more maturity to them because now I have some ability to reflect in a way that I didn’t at the time.

Even when it comes to criticism, something I’ve been thinking about is how much games writing is reaction instead of analysis or criticism. And part of that is a matter of time. I’m still feeling whatever a game wanted me to feel when I have to sit down to write about it to meet an embargo.

Yeah, for sure. A lot of these problems are very much created by the way that we live. I have written multiple reviews that I would write differently upon reflection. It’s really difficult to overcome, especially when you’re a freelancer and you don’t have time.

But you’re publishing a book, and you co-edit a journal. These are forms most games critics are not accustomed to. What have you found working in long form?

Writing in long form is hard for me. I have instincts towards being succinct, especially writing on a deadline, which is good, but I struggled writing the new essays for my book because they had so much more room to play and to explore and I had time to make different kinds of points or bring things in that I don’t think at the scale of. The book ended up being a little bit longer than I intended it, but I didn’t really go out of scope or anything. I struggled with finding ways to play in that space and making it make sense to myself because I’m so used to being constrained to one thousand words that it felt very odd to be able to do whatever I wanted within certain bounds.

The new piece I wrote about Dark Souls and disability, the way those games portray disability and how that ties into how accessible they are and the discourse around that, was the easiest piece to write because it was directly responding to discourse I had seen. Working through something very specific and direct. But I have a set of essays that’s about divine feminines. They’re short essays about multiple divine feminine figures and that was, Well, I could do whatever I want here. And that was very odd. I’m also trying to write fiction these days, and it is such a different muscle to flex. I feel like short form has toned my brain in a specific way that in some ways is really helpful and in some ways is difficult for me to play because I can be very narrow minded.

I think of writing as braiding strands together. And when you have a longer word-count, you can add more strands, but then you have to be accustomed to connecting them. The outline becomes much more important, but when I’m writing a thousand words I don’t often work with an outline.

I kind of have an outline in my head. I’m actually writing by hand a lot more this year.

It seems like a trend.

Yeah, but I used to outline because I would have two or three paragraphs in my head and I would write those out and I’m like, Okay, this one’s towards the end and this one’s in the middle somewhere and this one’s maybe the beginning or second paragraph or something, and then in the process of writing would fill in the gaps between each of these points. The thing that writing by hand has helped me do is move from A to B to C and have a very linear sense of my argument, which I think is really important in in short form, that it’s very straightforward and clear. That’s the weird thing about writing like fiction and poetry, is that clarity is not necessarily important. It can be but it isn’t necessarily. I think that’s very difficult for me to wrap my mind around sometimes, because so often my objective is to be clear and direct and to write in a very unambiguous way.

———

Autumn Wright is a critic of all things apocalyptic. Follow them @theautumnwright.bsky.social.