Draw!: Reaching the End of the Line in Dungeon Scrawlers

I see board games in the store and they always look so cool and then I buy them and bring them home, I’m so excited to open them, and then I play them, like, twice… This column is dedicated to the love of games for those of us whose eyes may be bigger than our stomachs when it comes to playing, and the joy that we can all take from games, even if we don’t play them very often.

———

Ever since the release of Dungeon! all the way back in 1975, the dungeon crawler subgenre has followed two distinct and equally important paths. One seeks to recreate the complexity of a dungeon delving tabletop RPG in board game form – the extreme end of that sort of thinking is probably something like Gloomhaven, a game so vast and expansive and huge that just playing D&D is probably simpler.

This, which has largely become the main path for dungeon crawl experiences, seeks to import to the board game as much as possible from the RPG experience, complete with elaborate rules, complex adventures, character growth mechanics, and more. The other path, however, goes in a very different direction.

Instead of aiming to reproduce the experience of playing a game like Dungeons & Dragons, it seeks to simplify it through abstraction, in an effort to make the whole process faster, simpler, and more accessible – squeezing some of that dungeon crawl juice into a format that doesn’t cover your entire kitchen table and consume all of an afternoon.

Enter Dungeon Scrawlers from 2021, one of the more recent games to attempt this delicate alchemy. Released by Wiz Kids and officially licensed with Dungeons & Dragons branding, Dungeon Scrawlers is part of a miniature subgenre of dungeon crawl games that have less in common with a game of D&D than they do with those mazes you used to do in activity books when you were a kid.

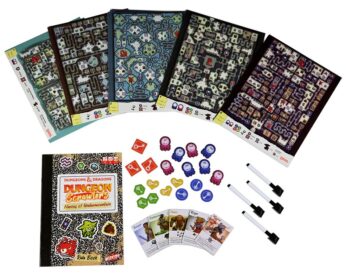

As such, the basic premise is familiar to anyone who has ever done a maze. You have a marker and an erasable, laminated board representing one of ten “dungeons” included in the base game. Your goal is to trace an unbroken line through the dungeon, from the starting point to the exit, and arrive before any of the other players can do the same.

Of course, in the effort to simulate the dungeon crawl experience, things are a little more complicated than that. You don’t just go through the dungeon, you also interact with its various inhabitants. Spells must be cast by tracing them, treasure must be collected by outlining it, and monsters must be defeated by coloring them in. Then, at the end of each dungeon, you’ll face a big, bad boss monster.

Heightening the (admittedly limited) RPG elements, each player chooses a character from one of five archetypes (rogue, ranger, cleric, wizard, barbarian), who each have a special ability that makes the game slightly easier for them. The rogue, for example, can collect a treasure simply by touching it with their line, rather than tracing around it.

Nor is the goal simply to reach the end of the maze fastest. You’re also collecting victory points as you go, which you do by defeating monsters, collecting treasures and exotic plants, casting spells, rescuing prisoners, and assembling artifact fragments, to name a few. Some of the dungeons also add their own wrinkles to the process, including teleportation portals, locked doors which can only be opened with corresponding keys, and so on.

Despite these additional complexities, however, Dungeon Scrawlers has much more in common with the placemat at a fast food restaurant than with a game of Dungeons & Dragons, and you’ll quickly find that the game rewards speed above almost anything else.

This is all in the first Dungeon Scrawlers release, “Heroes of Undermountain,” which has since been complemented by another iteration, “Heroes of Waterdeep,” which has different artwork, but a similar play style.

As you can probably guess from the subtitles, what mainly separates Dungeon Scrawlers from a number of other games that have tried this same formula is the D&D branding, which means that, besides fantasy mainstays such as goblins and wolves and skeletons, you’ll face a big myconid, a beholder, an illithid, and other familiar D&D baddies as you scrawl your way through the various dungeons presented herein.

(Not to mention some odder inclusions such as a scorpion man reminiscent of the one in Dragon Strike, or a weird armored skull robot guy who looks a bit like the X-Men villain Holocaust. Are these also standard D&D monsters? Probably. Do I know what they are just from their art in this game? I do not, and the game doesn’t tell me.)

Ultimately, a game like this, whether it’s Dungeon Scrawlers or any of the other variations available on the market, is going to appeal primarily to folks with kids. While the box suggests that Dungeon Scrawlers is suitable for ages ten and up, community consensus places that lower end at more like ages five or six.

Tracing mazes is a thing that pretty much all kids figure out how to do relatively early on, providing an opportunity for D&D fans to introduce their kids to the world of the game through a form of play that is more intuitive than more fully immersive RPGs, and more kid-friendly than a fiddly dungeon crawl board game.

There’s also the fact that Dungeon Scrawlers plays fast. There are rules and opportunities to string together multiple dungeons into a “campaign,” but because you’re doing little more than filling in mazes as quickly as possible, you can play through multiple dungeons in just a matter of minutes. The standard game says to play three dungeons, and that you’ll spend about fifteen minutes doing it – most dungeon crawl games can’t even get set up in that time.

———

Orrin Grey is a writer, editor, game designer, and amateur film scholar who loves to write about monsters, movies, and monster movies. He’s the author of several spooky books, including How to See Ghosts & Other Figments. You can find him online at orringrey.com.