So Much for Being Subtle

The prospect of the upcoming remakes of Max Payne and Max Payne 2 kind of bypass my normal critical senses and dubiousness. Preservation. History. Creative bankruptcy. Whatever, I don’t care. It’s more Max Payne – if games still came in boxes, I’d be queuing up for this at midnight.

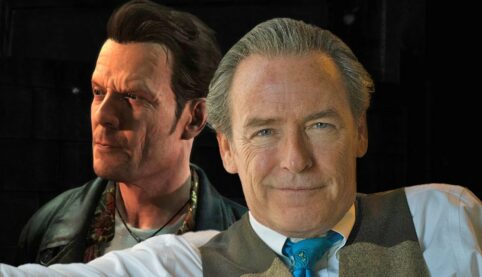

But now James McCaffrey is dead and I’m not that excited anymore, and I can’t think of another game or game series where, if they were making a new one, and then the lead actor died, I’d lose all my enthusiasm. Or, put another way, I can’t think of any other videogame where the main performance is so essentially and inextricably tied to the meaning and the experience of playing and the resonance of the whole thing. I can imagine X videogame without Y actor. I can’t imagine, and don’t really care to imagine, Max Payne without James McCaffrey. I know it’s possible – of course it’s possible. Remedy is still going to make those remakes and they’ll get someone good and I’ll play the games and I’m pretty sure I’ll like them. But James McCaffrey, in the original Max Payne especially, he’s not only performing the dialogue; he’s not only using his voice to give this character their character. James McCaffrey’s performance is the spirit of Max Payne as an artwork. His performance is the entire intellectual and expressive and emotional project of that game, if it had a voice. When he speaks, it’s the whole game speaking.

The qualities of his performance, and I suppose any performance, are abstract and hard to reverse engineer – and when you reverse engineer them you probably strip them of part of what makes them beautiful. But I think there’s value in trying to deconstruct James McCaffrey in Max Payne, initially as an homage to what is possibly the single greatest performance in a videogame, but also to elucidate and extrapolate and accredit the idea of performance in the culture of videogames. Videogames, generally, artistically, suffer from the precedence that is given to design. It’s all about design. Everything has to be designed. When you learn to make games and what’s important in games and what people want who play games, you’re talking and reading and learning about design. And design is valuable and crucial, but it often feels like games are not as interested in spontaneity and the abstract and the ineffable. It’s mechanics, and it’s loops, and it’s flow, and it’s readability, and while all those are compelling and esoteric components of videogame language, a really human, organic performance can be the counterweight to all that computational stuff. We need more personal energy in videogames. It’s all too algorithms and telemetry. A really connective and empathetic performance, it can make all the numbers feel like they mean something.

So, one thing that James McCaffrey does in Max Payne, he makes sure that there’s room for the other characters. That deadpan voice and that monotone delivery, it means he’s kind of playing the straight man, so when characters like Vinnie Gognitti and Jack Lupino and B.B. are on screen, the comedy and enormity of those characters can be felt – because James McCaffrey as Max Payne is so level and grave, and almost muted, it makes space and adds volume to Vinnie Gognitti’s peevishness, and Jack Lupino’s ranting and raving, and B.B’s quisling smarm. That rhythmic, never-rising, never-falling delivery creates a kind of base reality for the world of Max Payne, so when it goes big, either with these supporting characters or the nightmare sequences, or any of its other flourishes, you can really feel that bigness. He creates a kind of low register and when those other characters appear, it’s like spikes on a graphic equalizer.

It’s that same low register – that monotone – that gives Max Payne, as in the character, an enormous amount of his personality. It’s unspoken, in the sense that Max Payne never talks to any of the other characters or to the audience about it, but he’s crushed. At the beginning of the game, Max finds his wife and his newborn daughter murdered in their home. I don’t think this moment can be overstated – as far as I’m aware, Max Payne is the only videogame, or at least the only mainstream, big-commercial game where there’s a dead baby, your character’s dead baby. You can talk about Manhunt and Hotline Miami, and the other truly nasty and purposefully obscene videogames, but, without wanting to sound flippant, Max Payne has a unique claim in the atrocity stakes. And James McCaffrey’s voice, it holds all of that tragedy and repressed anguish and that soul death together. It’s not emotionless. It’s the voice of someone sitting on a chest full of emotions trying to press the lid down with all of their weight.

There are moments in Max Payne 3 where his voice and his temper boil over. In one scene, the corrupt police captain, Becker, and the arch villain Victor Branco have just escaped, again, and Max kicks the door that they’ve locked behind them and screams “goddamnit!”’ In another, he walks out onto a rooftop, surrounded by gunmen, brandishing the detonator to a bomb that he’s armed on the building’s foundations. It’s maybe the first time in the entire series where it feels like he’s losing control, where he’s starting to rant and rave – there’s a fantastic line where the villain, Neves, who has a thick local accent, boasts that he knows a lot of “powerful people,” and Max replies in a mocking, caricatured Brazilian voice: “well, your ‘paaaaaah-er-ful’ people aren’t gonna help you out of this one, buddy.” And you can just see, just for a second, the mask – the shield – starting to slip, all that madness, aggression and compressed suffering finally threatening to explode out. The greatest moment in perhaps the entire Max Payne series is during Max Payne 3’s second New Jersey level, when Max is being shot at by gangsters and he has to take cover behind the gravestone of his wife and daughter, literally hiding behind their deaths and his loss.

But in the first Max Payne, although he sometimes sounds like he might erupt, he never does. You get a sense of boiling, subcutaneous rage, but also someone who’s defeated, and become disconnected from reality at some level. He has those nightmares, where his wife and baby are screaming at him, and the world is covered in blood, and he’s falling and dying and drowning, but then Max wakes up and he goes back to his give-nothing-away monotone. He’s a killer, and there’s obviously something about him that’s very cool, but James McCaffrey makes sure that Max Payne isn’t a badass. He’s sadder than that. The game’s whole world becomes sadder. It’s something that plays out more in Max Payne 2, where Max, talking about the events of the first game, says that killing all the people that murdered his wife and his daughter “just made it worse.” That level in Max’s apartment in Max Payne 2, you find the recordings that the hitmen have been making of his outgoing calls. One of them is to a phone sex line. He asks to speak to “Mona,” and when she comes on the line, he starts talking about how empty he feels and how killing everybody couldn’t bring back his wife and his baby. “Mona” gets freaked out and Max apologizes and hangs up. If we’re talking about action heroes in mainstream videogames, this could be the most pathetic thing that any member of that pantheon has ever done. And all of that pathos is there in James McCaffrey’s voice. These other layers of the character become more explicit in the sequels, but they’re there from the first game, thanks to him.

But the biggest quality of his performance is how it contextualizes and makes a strange kind of sense out of the abstractions of Remedy’s world. The Max Payne games can be extremely dark. There are moments of 1970s, verité, street-level realism – the first game is set in subway stations, hotels, warehouses and nightclubs. But the games are also expressionistic and absurdist. The in-world TV show Address Unknown, a parody of Twin Peaks, is telling. The same way that David Lynch and Mark Frost take an idyllic American town and insert into it monsters and hallucinations and grotesque tragedies, the world of Max Payne as created by Remedy is an intersection between the real and the ultra-real, the fever-real, the horror-real. Lynch creates an equivalency between these two seemingly disjointed realities through his sets and his photography – two guys have a shot-reverse shot conversation at a Winkie’s diner, and there’s a monster outside. Remedy does it with James McCaffrey. His voice is level and grounded. It has earthly weight. He makes Max Payne sound down beaten and beleaguered, in a way that we instinctively recognise as “real”. At the same time, James McCaffrey’s voice is so deep and full of hard-boiled character, it becomes a caricature – he has a familiar, “realistic” pain, but his performance is also a burlesque of those emotions and experiences.

And that’s why he is the sound of the world of Max Payne, a world where there are drug dealers and murders and homicide investigations, and also mask-wearing gangsters who worship Satan, and a nightclub called Ragnarok, and a boat called the Charon, and the Illuminati, and an assassin who loves cartoons. In every possible sense, James McCaffrey is – was – Max Payne.

———

Edward Smith is a writer from the UK who co-edits Bullet Points Monthly.