Graphics Are Never Everything

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #184. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Here’s the Thing is where Rob dumps his random thoughts and strong opinions on all manner of nerdy subjects – from videogames and movies to board games and toys.

———

Now I will absolutely admit that videogame graphics can make a huge difference in how we perceive them. Not just literally, I mean. Seeing some of my favorite titles from multiple decades ago get a more modern visual upgrade – through a HD release, remaster or full-on remake – has been fantastic, too.

Here’s the thing: That’s not why I dislike placing graphics on such a high pedestal. What bothers me is when we value exceedingly detailed textures, dauntingly complex 3D models and other fancy graphical elements above all else.

A game’s graphics are, much like its soundtrack, story and gameplay, an intentional stylistic choice made within the limitations of what’s available to the development team at the time. Games are not their graphics – they’re all of their disparate parts and elements rolled into a single (usually) interactive piece of media. And sometimes a conscious choice is made to use visuals that are decidedly not painterly or realistic or otherwise impressive to look at, because it fits with what the game is trying to do.

The reason I’m bringing this up now, when it’s a losing battle so many others have been trying to fight for 20+ years (maybe even 30 or 40+ years?), is because of two games I’ve been playing a lot of lately: Caves of Qud and A Dark Room.

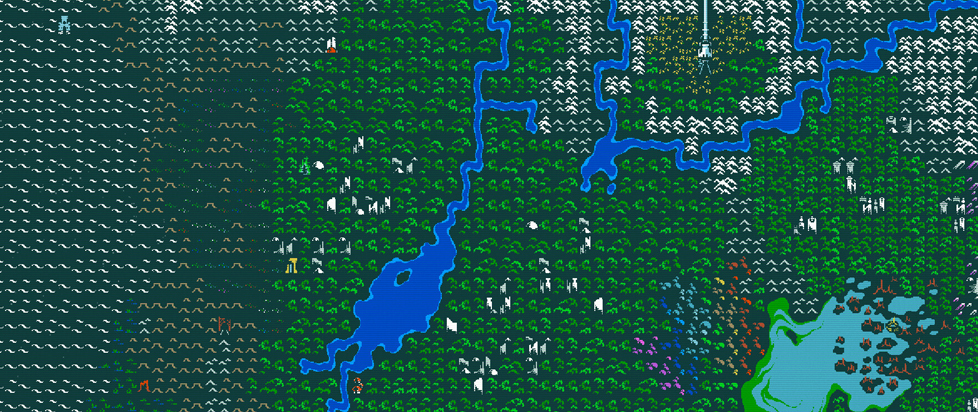

As of writing, Caves of Qud has recently had its 1.0 release, having previously been in development and Early Access for over 15 years. With that official full launch has come heaps of well-deserved praise, but also some derision – specifically when it comes to the simple-looking ASCII-style . . . well . . . style.

It probably doesn’t look like much in screenshots with no context, but Caves of Qud is so much more than how it looks. Even though I’d argue that, once you learn that context and begin to understand its visual language enough to recognize familiar elements, it can be quite pretty at times.

Beneath this grid of colorful icons and blank space is a vast and fascinating post-apocalyptic world that’s so post-apocalypse it might as well be a surreal alien planet on the other side of the universe. A world where what looks like two clusters of pixels smacking into each other represents a frenzied battle for survival as you make use of all your character’s skills and items in order to survive.

Chop off an angry tortoise’s leg in order to slow it down even more, then put some distance between you and start using that sniper rifle you found in some ruins a little while ago. Or accidentally chop off a bear’s face, which you can then don like a mask and drastically decrease your reputation with other bears. Use a pickaxe to tunnel around a hazardous open shaft in the ground to who knows where, then accidentally stumble upon a walking mortar turret fighting with a swarm of crabs.

As bizarre and enticing as some of these scenarios may seem, they’re 1) tame in comparison to some of the things other players have experienced, and 2) not the only reason to give the game a try. There’s a lot of really interesting lore to uncover and characters to meet. The procedurally generated elements can be a bit too strange to really understand sometimes, but the non-randomly generated lore is . . . just . . . so good. To the point where I’ve started looking forward to encountering something new so I can read up about it. I am not joking.

Then there’s A Dark Room. A game that I was championing as far back as 2014 (specifically the iPhone release). There’s even less to look at here, with the bulk of the game appearing to be simple text menus that don’t really do much. But that’s also a big part of its brilliance. Very mild spoilers for a 10+ year old game from here on out.

What starts as a terse, almost bleak handful of sentences and a single task to get a fire going, eventually starts to grow into something more. As the fire springs to life, the colors on the screen shift from a black background with white text to something more like a dull grey background with dark text – and the contrast shifts even more once the fire is fulling roaring.

After a few moments you have to get more wood, which gives you a new menu choice to go into the forest and collect some. Accompanying sound effects start to lend a sense of . . . I don’t want to say “realism” but it’s kind of along those lines . . . to what you’re doing. Before long a lone wanderer stumbles in, so you leave her to warm up while going to grab more firewood.

But she’s not just a wanderer – she’s a builder. Now, in addition to keeping the fire stoked and collecting wood, you can build traps to harvest materials like fur and meat from, in addition to huts. Huts attract more wandering folk, who can then be tasked with collecting wood for you.

All the while the occasional message will pop up describing how the builder is doing, how your unseen character is feeling or let you choose whether or not to give some of your precious wood and meat to a visitor asking for a place to spend the night. And all the while, things feel just a little bit off. Like the world at large is in a very bad state, but nobody is talking about it. Maybe they’re too tired, or too broken to.

Eventually you’ve built yourself a small community, complete with a smokehouse for curing meat and a trading post that you can use to exchange furs for other items, including a compass. With nothing else to do but wait to stockpile enough materials to build more traps and huts, you trade for it. Now there’s a new menu option – one that asks you to choose your supplies before selecting “embark” from the top of the screen.

The way A Dark Room smoothly shifts from what looks to be a word-heavy idle game into a fight for survival as you start to map out the world around your little cluster of small homes is, to take a step back from all the dramatic wording, really fucking cool. After spending a fair bit of time looking at nothing but text, text boxes, and sometimes a progress bar inside a text box, suddenly encountering graphical elements (ASCII style elements, but still) is almost shocking.

It’s not just the unexpected appearance of something to look at that isn’t just text, either. Excursions into the surrounding area can be tricky and dangerous. You can’t go far because you only have so much water and food. Hostile beasts and scavengers pose a very real threat, too. And if you run out of sustenance or health you lose all of the items you collected on that trip, plus all of the supplies you initially brought along.

I know that’s a lot of words describing two games I really like, but it’s all for a reason. The point is that sometimes, when we place too much importance on what a game looks like – or even just how we perceive its visual style – we end up missing out.

Not all “simple” looking games are going to be as figuratively and literally deep as Caves of Qud, or unexpectedly change genres partway through in such a masterful way as A Dark Room. And I could argue about how not all visually impressive games are actually enjoyable to play (I won’t, though). But by purposely ignoring a game that might sound interesting while maybe not initially looking it, we’re ultimately doing ourselves a disservice.

Enjoy hyper realistic graphics! Bask in gorgeous 3D digital vistas! There’s nothing wrong about any of that! But please also try not to let that be the only thing (or even the primary thing) you want from the games you play. There’s value in simplicity, too.

———

Rob Rich is a guy who’s loved nerdy stuff since the 80s, from videogames to Anime to Godzilla to Power Rangers toys to Transformers, and has had the good fortune of being able to write about them all. He’s also editor for the Games section of Exploits! You can still find him on Bluesky and Mastodon.