I Too Bought a PS5 for a Single Game, I Too Bear Great Regret

Winter 2024 was a lot of hemming and hawing over whether it was time to buy a PlayStation 5. Final Fantasy VII Rebirth – both a remake of a game I’d played for the first time during the pandemic and loved, and sequel to a game I’d played also for the first time during the pandemic and loved – had finally broken me. I knew it would come to a device I already owned eventually, to some degree of “playable”, but I determined I wanted it as soon as possible. I wanted to know what was going to happen to my pretend pals. I wanted to be in the conversation with my real pals about our pretend pals.

A year later, the game is no longer a PS5-exclusive title. It’s on PC. You can even play it on a Steam Deck, a device I already owned at the time I bought the PS5. I’m not even close to seeing the credits roll on Final Fantasy VII Rebirth.

The game itself was $69. The device to play it on was $499.

Unlike books or movies, videogames are a medium with a complicated and expensive barrier to entry. The choice was either A) buy a PS5 and play the game now, or B) wait an indeterminate amount of time to play the game later, assuming it ran ok on something I already owned. I suppose there was also C) let go of this desire. But no one likes option C; it’s tough to make “stop wanting a thing” sound like the compelling option. It’s hard enough to make waiting feel viable, even if, rationally, it seems like the obvious thing to do. None of us are immune from the ecstasies of consumerism.

“Sure, it’s expensive, but it’s for more than just one game, eventually. It’s still new,” my mom – in a casual catching-up phone call – weighed in on rationalizing what still felt like an irresponsible if not wasteful purchase, fully unaware that the PlayStation 5 was in fact three years old at that point, and that the outlook for how many more games it would get – will get – was a little bleak. Games that I couldn’t play elsewhere, anyway – for instance on my PlayStation 4 or my Steam Deck (the latter of which was a purchase I had made because, as a fairly casual videogame player who only plays games a few hours a week if at all, it seemed like the lowest-fuss and least expensive way to get access to PC games again).

“It’s not like you’ll never use it,” my mom said as I imagined another timeline where I never felt the need to buy a PlayStation 5 at all. Presumably my mom’s frame of reference was more so my childhood Christmas where I got a GameCube. The excitement of this console and all of its games that came on weird little CDs stood apart from the old Nintendo console and all of its games that came on weird little cartridges. In contrast, the PS5’s Game Boost technology for running PS4 games faster and smoother doesn’t quite capture the magic of Christmas. That’s hardly a failure on Sony’s part, of course, and no one would argue that a lower barrier to backwards compatibility is a bad thing (ask the PS3). But the purchase felt hard to rationalize.

The phone call with my mom instead stood in stark contrast with a phone call I had a decade ago with my girlfriend at the time, similarly hemming and hawing about buying a Nintendo 3DS. Her argument in favor was that it wasn’t an impulse purchase; I’d been thinking about buying this for a while. And somewhere in there might be the difference. Then, I had been thinking about buying a 3DS for a while. Now, I had been thinking about buying a game for a while – not a PS5.

———

It’s possible that this is all just a lot of words about sticker shock. $600 is a high barrier to entry for, essentially, one game – although, adjusting for inflation, the original PlayStation also cost about $600. Game development is more expensive and time-consuming than ever. Final Fantasy VII Remake began development five years prior to its release, the same length as the lifespans of the consoles of my youth. I’m not complaining about why this hobby is so expensive; the more you look into it, the question becomes why aren’t videogames more expensive. The ”I want shorter games with worse graphics made by people who are paid more to work less and I’m not kidding” meme only grows stronger with every new round of mass layoffs.

It’s also possible that this is all about hype. It’d be an easy explanation for the regret if it were just that I spent a lot of money to access a game that fell short of my expectations. And the game itself is fine. It started off like everything I could have wanted, then I fell off as the narrative pacing and bloated open-world design ground the game to a comically slow drag. Now, almost a year after the its release, I still haven’t finished Rebirth, which means that I haven’t even read any of the analyses of this game (even as vaguely unconcerned about spoilers as I am, I have to draw a line somewhere), a title I was so desperate for that I dropped half a thousand dollars on it. (I mean, “Guide me, oh, Tifa”? I bet the queer readings of this game are popping off. Not that I’ll know for probably another one or two dozen hours before I can see for myself without prematurely learning the ending.)

Maybe the issue is with me and my own time management, then. Had I known how busy a year I’d have (and had I known the exclusivity window would be only a year, and that it sounds like it actually runs rather nicely on Steam Deck), then maybe I wouldn’t have felt the pressure to experience this game as fast as possible to read with and engage with the games crit reactions as soon as possible – which I still haven’t done. Maybe. We always think we have more time than we do.

It doesn’t really feel fair to claim that I bought a PS5 solely to play a single videogame and regretted doing so. I’m not even sure if what this emotion is is regret. A late capitalist media landscape of franchises and reboots often leaves an unpleasant aftertaste of feeling like you’re an easy mark, ranging from the J.J. Abrams–precision weaponized nostalgia of The Force Awakens to the live-action remakes of Disney movies coming out like clockwork despite the fact that they’ve gotten to the ones that – since you can’t use real lions or a real Stitch – don’t even make sense. The problem here is that by reframing the relationship between a text and an audience as the relationship between content and consumers, we’ve recentered art as a transactional experience. And everyone likes to think of themselves as a savvy shopper.

———

I feel a certain pride that, since I didn’t grow up with a PlayStation and only played the original Final Fantasy VII in my late twenties and loved it with my real adult brain, nostalgia didn’t play into this decision. This is kind of a dumb thing to feel pride about, but when you’re managing your sense of regret, any port in a storm.

But it sure is dumb, especially because, as far as nostalgia goes, the history for this one is pretty notable.

It’s appropriate that the game at the center of this console-centric displacement is a new take on Final Fantasy VII, a hit game that came out during an awkward window in the evolution of the graphics consoles were capable of where it demanded an eventual remake. A game that came out on the PlayStation instead of a Nintendo console like all previous games because Square weighed the new hardware options against each other and made a call that famously pissed off Nintendo for a decade.

“The first time I ever heard someone allude to a remake of Final Fantasy VII was also the first time I ever saw Final Fantasy VII.” Tim Rogers recounts in his video essay/review of Final Fantasy VII Remake, telling the tale of a friend who primarily played PC games watching the Final Fantasy VII demo on PlayStation, asking “‘why can’t the whole game just look like this?’” during the cutscenes, albeit knowing full well how hardware limitations worked. Rogers notes this person was “just being a hater”, but further explains that – because of the unique moment in technological advances and limitations when Final Fantasy VII was made – “the original Final Fantasy VII was a machine that begged us to beg its makers to make it again”:

“As the result of a large team of artists experimenting with a vast range of new styles and techniques, Final Fantasy VII arrived as a sort of a half-baked mixed media project…. One might say that the original Final Fantasy VII began the mainstream conversation regarding the disparity between cutscene graphics and in-game graphics…. Furthermore, the battle scenes used realistically proportioned characters while the traversal segments used lower-polygon chibi models. The actual game showcased more than one flavor of graphical disparity even between cutscenes: some cutscenes used the fanciest CG models, some used the lower-polygon, toaster-handed models. … As we watched technology march forward in later years, many of us looked back at Final Fantasy VII and yearned…. Two years post Final Fantasy VII, we had Final Fantasy VIII, a game whose in-game character models achieved realistic human proportions. Suddenly, Final Fantasy VII acquired the grime of a baby’s toy.”

It feels appropriate that the remake of this game – albeit the middle third of it, the first third of course releasing for a different generation of PlayStation, and where the finale might’ve been on yet another if the sales numbers were better – is the one that nudged me to buy a new console for it. Even if the console itself somehow felt incidental to its own progress.

———

All that said, the videogame console as a unique device doesn’t just feel different in the 2020s based (solely) on the oddities of growing older and witnessing how your hobbies do or do not grow up with you. It is attributable to how the console plays a different role now.

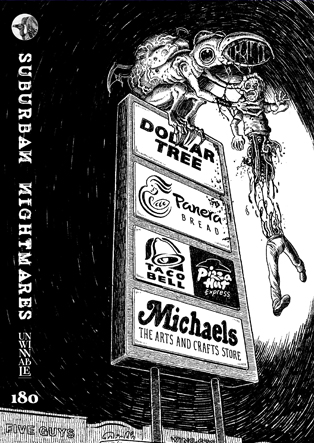

Playing videogames has ceased to be the exclusive domain of “gamers” for a while now, which you can see anywhere from your non-gamer friends trying desperately to acquire a Nintendo Switch in the first month of the pandemic to the many, many cops getting paid an obscene amount of the city budget to play Candy Crush on the subway. Yet owning a console seems to swing every few years between a normal-ass thing for anyone to own (like with the Nintendo Switch or the Wii before it) vs a Serious Hobbyist Thing (they called that thing the PS4 Pro). The PS5, vibes-wise, is solidly in the Serious Gamer camp. Your purchase comes with a complimentary identity whether you like it or not. Buying a PS5 in 2024 felt like a label and an upgrade I didn’t ask for, all for the sake of my investment in one story.

The console, as a share of where people play videogames, began to stagnate in 2011. A talk titled “The State of Video Gaming in 2025” given by the CEO of investment strategy firm Epyllion (hear me out, I promise this is going to sound Normal) posited that, in an environment where games cross-release across platforms and console exclusives are less and less of a thing, “hundreds of millions of children growing up on Roblox are unlikely to ask for a $500 console to play AAA games.” When I did cave and buy that 3DS in 2015, I brought it with me to pass the time in a laundromat and a child asked me how I was playing the game without touching the screen. While I remember middle school as a big, dumb argument over the PS2, Xbox, and GameCube, today’s middle schoolers’ horses are in completely different races. I don’t bemoan that today’s children maybe don’t know what a horse is (metaphorically speaking), but I do bemoan that I’m now begrudgingly buying the newest horses.

Technologically, consoles aren’t as important to the medium as they used to be, now that consoles are somewhat more indistinguishable from any other computer you have in your pocket or on your desk. “Games aren’t films. They’re not books. They’re made for distinct pieces of technology that are intentionally sunsetted and changed,” Frank Cifaldi explains on an episode of the Insert Credit podcast discussing why so many videogames go out of print and why video game preservation is so poor. “Any movie is just a synchronized series of still images and audio. So movies are infinitely portable to whatever the next thing is that plays movies. Games do not live in that world. Games are made for distinct pieces of hardware that are almost never backwards compatible.” It’s a good thing that this is – although I’m sure this is technically incorrect – somewhat less true now than it was in the era of the N64 or Sega Saturn, which were such strange pieces of hardware that they’re still difficult to emulate games for. It just stings more when, emerging like Robin Williams from Jumanji asking what year it is, it is true again, like when I walked into a GameStop resigned to the fact that caring about Final Fantasy was about to cost me over half a thousand dollars.

———

My mom asked if the PlayStation 5 looked better. I told her that the characters have arm hairs now. We agreed that this bordered on perhaps just a little too much.

———

Matthew Weddig (he/him) is an editor and guitarist currently writing a book about dating and romance in video games. He lives in Brooklyn, where he makes his cat watch horror movies with him. He sort of posts on Instagram and BlueSky, and his bylines, poetry, and bands can be found at linktr.ee/matthewjulius.