Skin Like A Waxen Peel: Revisiting Everything Everything’s “Photoshop Handsome” in the age of AI Image Slop

At the beginning of 2025, Instagram made headlines for less than ideal reasons. Select users were being shown AI generated images of themselves in stylized, but entirely fabricated pictures. Unsurprisingly, many people found the idea of being confronted with an almost-lifelike, polished version of themselves to be somewhat unsettling, and the implications of such an image being trained on hundreds of personal photos downright violating. Given the recent popularity of generative imagery, however, perhaps this was the inevitable endpoint of a social media platform so reliant on self-image.

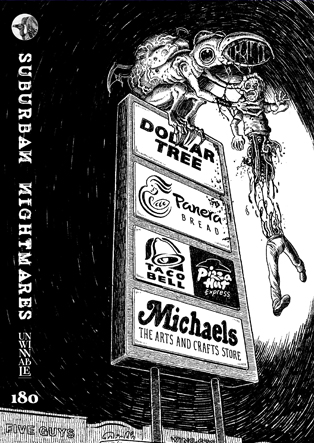

It’s hard to spend any length of time online in 2025 and not be confronted with some form of AI image. From low-effort political memes and comment-farming Facebook posts of idyllic designer kitchens to mangled diagrams in poorly-vetted scientific papers, these images have infiltrated almost every corner of the internet. Aside from the messes of human limbs, and blurred, nonsensical text which are often the first giveaway of genAI, there tends to also be a hard-to-describe sheen of unreality, an uncanny glaze on the image’s surface, like the iridescence of gasoline sitting on the surface of a puddle. This uncanniness is often most noticeable, and most off-putting, when the image is approximating a human likeness.

In May of 2009, more than a decade before these kinds of images would become so mainstream, a newly-formed art rock band from Manchester called Everything Everything would release the single “Photoshop Handsome”. The band’s second single, it’s a punchy, if unsubtle, screed at the prevalence of manipulating images of the human form to sell you things. While the lyrics mainly concern Photoshop and its impact on our perception of the world, they have proven to be unintentionally prescient, sharply evoking the strange veneer which coats the current digital landscape in which we find ourselves. Many of lead singer Jonathan Higgs’ trademark cryptic turns of phrase specifically evoke that feeling of unease one feels upon seeing AI images of people: “I am one with the furniture… what have you done with my father? Why does he look like a carving? … my teeth dazzle like an igloo wall … chest pumped elegantly elephantine … watch your dorsal fin collapse.” Higgs’ reactions to the bombardment of processed portraiture which make up 21st century advertising evoke a sense of deep unease – these feelings are mirrored and magnified to a grotesque level when you zoom in on an AI’s vision of a party scene and find someone’s gleaming, grinning teeth stretching monstrously and impossibly around their jaws.

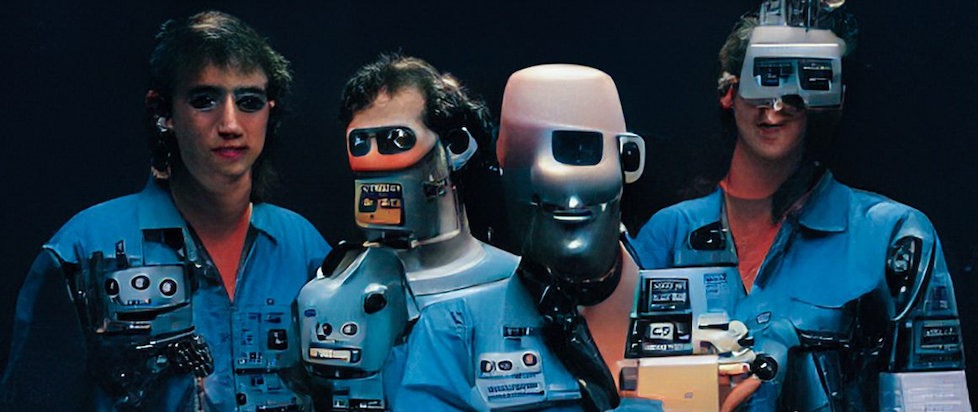

“Photoshop Handsome” has two music videos. In the 2009 original, at the song’s climatic instrumental breakdown, we see each member of the band imprisoned in a Photoshop window, their bodies being ravaged and bruised at the hands of an unseen tormentor, the cursor flying across the screen and beating them to a pulp. The metaphor here is pretty on the nose, but their depiction of humanity being beaten away is striking nonetheless. While this brutal imagery doesn’t immediately seem analogous to the more subtle processes involved in AI, a core idea of “Photoshop Handsome” is that impossibly-perfected images can have a significant impact on social psyche, and in that sense, they’re something which is inflicted upon us, just as AI is currently. Rather than being beaten into physical perfection, we now have a sort of subcutaneous parasite, scraping every facet of our faces from Instagram, and shoving them together like distinct scraps of dough into a muddy lump of vague resemblance without us having to ever think about it. Compared to the insidious way in which our images are actually being used now, the blatant use of a blunt tool like Photoshop seems almost quaint. Watching the video today, the more visually upsetting image is of Higgs with a swollen, shimmering face as he sings “I have skin like a waxen peel, and a face that I can never feel”.

The second video, released in 2010, is a more chaotic affair, with Everything Everything employing the services of 50 animators to mess with footage of the band’s performance as the animators saw fit, creating a frantic patchwork of surreal imagery. This seems like a very specific choice, with a kaleidoscope of imagery and explosion of creativity placed in stark contrast to the homogeneity which the song is railing against. Today, as this homogeneity is increasingly exacerbated through AI, a microcosm of concentrated creativity and craft like this is refreshing. This idea of using image manipulation creatively – “for good”, as it were – is described by Higgs in an interview with Clash: “The result is a very colourful and diverse explosion of ideas, the image of ourselves re-imagined hundreds of times in 3 minutes. We hope to open the imagination and raise some thoughts about what it means to change our perceptions of ourselves to the extent we do.” The end of the video descends into a glitching mess, the footage becoming increasingly smeared with compression artefacts – an aesthetic that would be found on the album art of their debut album Man Alive and its singles. From the outset, Everything Everything have concerned themselves with, and at times seem fascinated by, these images of digital corruption, and the constant feedback loop between the technology and the people which produce them.

The band would go on to have a prolific career, with songs often centering on themes of life and self in a world of near-complete digital infiltration. Indeed, they have since dealt with the subject of AI more explicitly. In 2022 the band would release Raw Data Feel, an album which not only addresses AI directly in its lyrics, but also uses deliberately nightmarish AI-generated imagery in the album’s album and promo art. Higgs, alongside Mark Hanslip from the University of York, actually developed a language model to write lyrics for the album, nicknamed “Kevin”. While these choices might seem at odds with the band’s apparent rejection of such fakery, or a betrayal of the creative process, their takes on contemporary issues, be they political, social, or technological, has always been driven as much by fascination as with judgement. Raw Data Feel encapsulates both an understanding of AIs inhumanity alongside an acceptance of the escape it could offer from the grimy drudgery of everyday reality. As Higgs’ put it in an interview with Rolling Stone: “You can use technology to cope and use someone else’s brain because you’re hurting when you use your own…. There’s this feeling now and again that I didn’t use myself for this. I used a proxy brain to deal with difficult things.” This understanding of people’s inherent flaws and weaknesses as part of the essential stuff of humanity is illustrated by Higgs’ choices of texts used to train Kevin: the complete terms and conditions of LinkedIn, Beowulf, the sayings of Confucius, and 400,000 comments from 4chan.

So perhaps Everything Everything has accepted their place among a modern digital nightmare, as much as we may want them to simply admonish it. Before all that though, that a song released in 2009 so aptly mirrors the state of the internet today is a testament to Jonathan Higgs’ talents as one of the most underrated British songwriters of the 2010s. In the Clash interview, he outlines the song’s central thesis: “What would it feel like to come back to life as one of the ‘perfected’, false, immortal beings that adorn magazine covers, adverts and games?” Give it a few years and maybe Instagram can show you – whether you want it to or not.

———

Jonathan is a biological researcher by day, but spends much of the rest of his time obsessing over games, music and music in games. You can follow him on Bluesky and at Medium.