Politics in the Ruins

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #183. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Architecture and games.

———

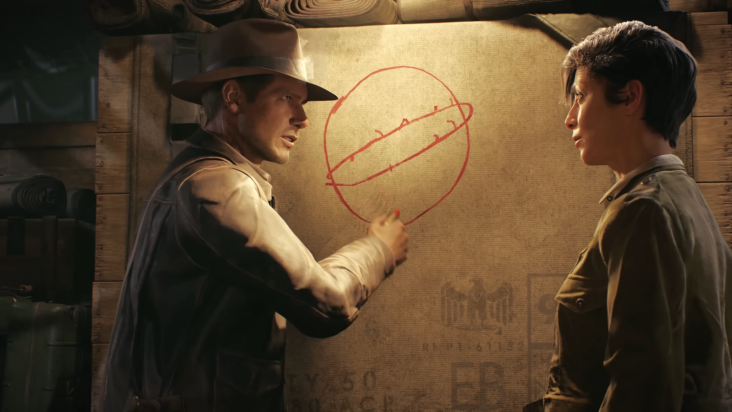

When I was growing up, I only ever wanted to be one of two things, a pilot or an archaeologist. I’ve always had a passion for aviation, and the past. As you might expect, Harrison Ford was my favorite actor, mostly because he got to be Indiana Jones and Han Solo. You can probably guess what my favorite movies were.

I’ve always enjoyed the Indiana Jones games, even though most of them aren’t great, with of course a few notable exceptions. The Fate of Atlantis remains a classic and at least in my personal opinion, The Emperor’s Tomb was at least, well, decent. In any case, I’ve been looking forward to The Great Circle for a while now, especially because the developer, MachineGames, pulled off the recent Wolfenstein reboots with such panache.

This doesn’t have much to do with videogames, but whenever I think about archaeology, I think about the problematic politics of this particular field. I know that I’ve approached the topic a few times before, but in the event that I dig up skeletons or tread familiar ground, please do just bear with me. I apologize in advance for the puns.

I believe that it’s worth keeping certain concerns in mind whenever engaging with the myriad of media touching on supposedly ancient history including The Great Circle. I’m not going to discuss any of the widely acknowledged issues, but I would like to say a thing or two about a problem which continues to this day, manipulation of the past for the political purposes of the present.

While the story is of course fictional, certain aspects of The Great Circle hint at the uncomfortable truth which is of course that archaeology is never actually neutral. Whether it’s the Athenian Acropolis or the Roman Forum, archaeological sites have quite frequently been made to serve political purposes. When you turn a critical eye to their development, you uncover stories of preservation, erasure and the fight to control the historical narrative, sometimes the result of unacknowledged bias, although frequently also the product of intentional fabrication.

Rising above the city of Athens, the Acropolis has always been much more than just a collection of temples and sanctuaries. The site is a powerful symbol of cultural heritage. The story of how it became such a symbol is on the other hand more a matter of nineteenth and twentieth century politics than ancient architecture.

When Greece gained independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1830, the new nation needed a unifying identity. Its leaders looked to the classical past for inspiration, specifically to the golden age of Athens. This was the era of Pericles, a fearless leader who oversaw the construction of the Parthenon, in addition to philosophers like Socrates and Plato. It was a time of democratic ideals and artistic achievement, values which resonated with perhaps overenthusiastic Enlightenment thinkers eager to see Greece as the cradle of western civilization, if not civilization in general.

With the passage of time, the Acropolis came to serve several different roles, notably a Byzantine church, a Venetian fortress and an Ottoman mosque, each layer telling a story of the people who lived there. In order to emphasize its classical roots, nineteenth century restoration projects on the other hand removed these later additions, obliterating their memory and erasing their meaning. The various Ottoman houses in the area were demolished and the minaret of the mosque was torn apart, along with anything else dating to after the supposedly classical period.

This cleansing of the Acropolis wasn’t just about archaeology, it was about nation building. Presenting the Acropolis as a pure, unbroken link to ancient Greece, the newly founded nation sought to align itself with the ideals of democracy and intellectualism which resonated with every manner of idealist in the western world at the time, denying their eastern traditions. The result was an erasure of the stories from Byzantine and Ottoman Athens, leaving a sanitized version of history serving contemporary aims.

As this vision of the past became solidified, the Acropolis turned into a focal point for Greek national identity, tourists flocking to Athens to see the cradle of democracy, as western scholars celebrated its restoration as a triumph of classical culture. This narrative on the other hand ignored the complicated history of the site, reducing it to a simplified symbol of ancient glory. The selective preservation has been shaping perceptions of Greece for generations, influencing everything from academic studies to representations of the ancient world in popular media.

In the same way that Athens turned into a symbol of democracy, the Roman Forum became a stage for imperial ambition, particularly under the dictator Benito Mussolini. In the early twentieth century, Italy was navigating its own crisis of identity, the fascist regime, led by Mussolini, seeking to connect modern Italy to the grandeur of ancient Rome, using archaeology as a tool to legitimize their authoritarian rule.

The site of the Forum, once the bustling heart of ancient Rome, had long since fallen into disrepair over the centuries, most of its marble having been scavenged for lime. The area was little more than a pasture known as the Campo Vaccino, Cow Field, by the Middle Ages. Medieval and Renaissance buildings eventually sprouted amidst the ruins, creating a patchwork of historical layers, but for Mussolini, this mixed landscape was a problem, and an opportunity.

Mussolini launched an ambitious campaign to restore the Roman Forum shortly after coming to power. This involved clearing out centuries of mostly Medieval and Renaissance structures to expose the ancient ruins beneath. Roads were torn up, homes were demolished and layers of history were removed, all in the name of uncovering the glorious imperial past. Mussolini constructed the Via dei Fori Imperiali, a grand boulevard cutting through the heart of the Roman Forum, something which still offers dramatic views of the classical ruins.

Mussolini’s project wasn’t just about celebrating the past. This was a deliberate statement linking the fascist regime to the might and glory of the Roman Empire. By erasing these later periods of history, the regime created a narrative which framed Mussolini as an heir to Caesar Augustus, a ruler destined to restore Italy to greatness.

The site became a tool for propaganda, hosting grand parades and public ceremonies designed to evoke the power of ancient Rome. Photographs and newsreels from the time show Mussolini striding through the ruins, surrounded by banners and cheering crowds. These images cemented the connection between fascist ideology and the imperial legacy of ancient Rome, leaving a lasting impact on how the Forum is perceived even today. Interesting to note is that Mussolini naturally restored the classical components dating the Imperial period, leaving the earlier structures from Republican Rome underground. They’ve actually never been fully excavated. As you might expect, the Forum played a critical role in the flourishing of democracy, but the dictator wasn’t particularly interested in highlighting these achievements.

Few places illustrate the intersection of archaeology and politics quite as vividly as Israel. In this country steeped in history, pretty much every stone carries cultural, religious and of course political significance. The modern state of Israel, established in 1948, has long used archaeology to strengthen its national identity, often in ways which have sparked controversy.

The most iconic example is the City of David, an archaeological site located just outside the Old City in Jerusalem. Excavations have uncovered evidence of ancient developments including structures and artifacts linked to the biblical King David, at least in theory. Israelis often consider this a tangible connection to their ancestral roots, reinforcing all manner of modern land claims.

The site’s excavation and subsequent development have naturally never been without conflict. Critics argue the focus on specifically Israeli history comes at the expense of other narratives, particularly those of the Palestinian residents who live nearby. The process of excavating and developing the site has led to tensions over landownership, displacement and the erasure of several thousand years of heritage.

These endeavors demonstrate the power of history to shape modern identities and territorial claims. For proponents, they offer a way to connect with a rich past, affirming national pride and cultural identity. For detractors, they represent a form of historical erasure and a powerful tool for the expression of political power. In this charged landscape, every archaeological discovery carries implications far beyond academia.

The story in The Great Circle has you navigating a world filled with similar dilemmas. The game’s central artifact, the eponymous Great Circle, supposedly has the power to shape the future, various factions of course attempting to control this power. The narrative reflects the very real debates surrounding sites like the Acropolis and the Roman Forum, among others. The central question is of course who gets to decide which parts of history are worth preserving and how a healthy respect for the past can be paired with progress.

The selective preservation of history is of course not unique to Greece, Italy or Israel. Around the world, archaeological sites have been manipulated to serve contemporary agendas. In the recent past, the reconstruction of certain Hindu temples at the expense of Mughal structures in India came to spark intense debates about national and religious identity. The destruction of Tibetan monasteries in China moreover exemplified how archaeology can be weaponized for ideological purposes.

In the Middle East, ancient sites have often been caught in the crossfire of modern conflicts. The deliberate destruction of cultural heritage, the ruins of Palmyra for example, has drawn international condemnation. These acts of erasure are not only attacks on history but are efforts to erase the identities and memories of entire communities.

This activity isn’t limited to any particular geographical area. The interpretation of historical sites in America including battlefields dating to the Civil War has frequently been shaped by political narratives. Decisions about what to preserve, what to emphasize and what to downplay are rarely neutral. They reflect the values and priorities of the time as well as the people in power.

Archaeological sites don’t just belong to universities or governments. They’re part of our shared cultural heritage. When communities become engaged in the process of preservation, we can all ensure that diverse voices are heard and respected. Public programs, museum exhibits and educational initiatives can help demystify archaeology, making the field more accessible. When people understand the stakes, they’re more likely to advocate for thoughtful, ethical preservation practices and when they see their own histories reflected in archaeological narratives, they’re more likely to feel a sense of connection and pride.

The Great Circle is a story about the power of history and the responsibility that comes with uncovering the past. Exploring ancient ruins while unraveling the mystery of the Great Circle, you’re forced to confront various questions about the ethics of archaeology, including what it means to preserve the past and who gets to decide what should be saved. The real stories of the Athenian Acropolis, Roman Forum and the City of David show us how these questions are anything but hypothetical. They remind us that history is not just something we study, it’s something that we shape. Learning from these examples, we can strive to create a more inclusive, nuanced approach to archaeology, one that honors the complexity of the past while building a more equitable future.

———

Justin Reeve is an archaeologist specializing in architecture, urbanism and spatial theory, but he can frequently be found writing about videogames, too.