Language Roots

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #183. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

What does digital grass feel like?

———

[This piece contains spoilers for Chants of Sennaar.]

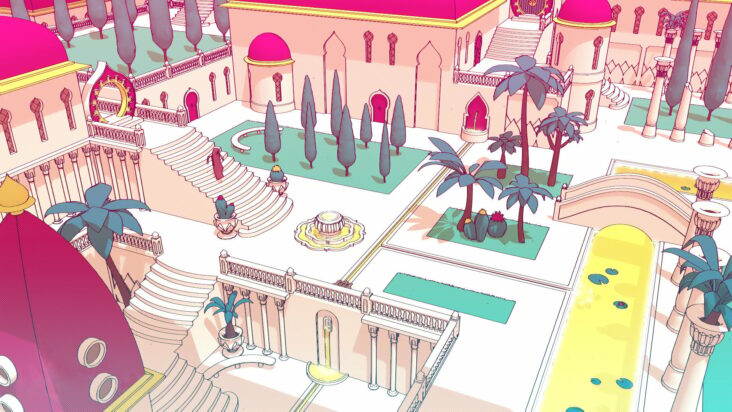

Chants of Sennaar is a language-based puzzle game set on a brightly-colored Tower of Babel, with dramatic architecture, views over unearthly vistas and five separate cultures that need to be understood in order to progress. But it builds that world using the familiar.

Almost immediately upon entering the first area, I hear a familiar rattle. It’s the alarm call of a Eurasian magpie. I can instantly approximate the location of the developers, and a quick Google confirms that they’re French. This game is situated somewhere close to me, even though the space I’m moving through is utterly alien.

In linguistics, there’s a concept-turned-meme called the “bouba/kiki effect.” In experiments in the 1920s, scientists found that people tended to associate certain sounds with certain shapes – bouba is rounded; kiki is sharp. These findings have held across many (but potentially not all) different native language groups. The language in the second area of Chants of Sennaar is most certainly kiki. Where the first language uses glyphs with both straight lines and curves, the second language is entirely angular.

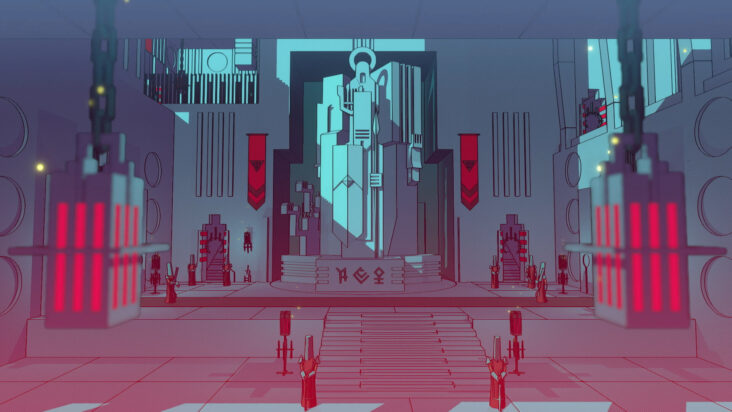

This second language is the language of the warriors. Where the first was a religious language, with words for devotee, abbey and church, the second is martial: fortress; weapon. The devotees are the only group with a word for God, and the warrior’s glyph for duty is very similar, creating an instant shortcut to understanding what’s important to them. And the warriors’ kiki-ish script emphasizes the difference, even before you’ve translated many words.

As well as determining vocabulary, it’s necessary to understand the different grammatical patterns of the languages in each area. In the first, for example, plurals are made by repeating the glyph, while the second has a plural marker that is placed before the noun. Both also use subject-verb-object sentence structure, like English.

The third language does not. The script it’s written in is reminiscent of Devanagari, a script used to write dozens of languages, many of which use different word orders than English. Although the Sennaar language uses object-subject-verb structure, which isn’t the default in any written language (although it is common in British Sign Language) the appearance of this sort of script primes the player to expect a shift in word order from what they’re expecting, both from their real-life language and from the languages they’ve been working in so far.

The people who speak the fourth language call themselves alchemists. The first and third languages have no known word for them. The former are separated by the warriors who block off access to the higher floors of the tower and the latter by a monster that makes traversing the gap dangerous. The warriors themselves call them scientists.

When colonists encountered native groups, they often ended up naming them based on exonyms – that is, what nearby groups called them. These names were often derogatory, and they often stuck. Apache means enemy. Cherokee may be a Muscogee term for people who speak a different language. Sioux is a shortening of “little snakes.”

In Chants of Sennar, the names different groups use for one another are often horizontal approximations, like the alchemist/scientist divide. But both the devotees and the warriors call the people on the third floor the chosen ones. There’s a reverence that extends into their culture, with the warriors believing it is their duty to protect the chosen, while the devotees are kept from visiting them, with the warriors calling the devotees impure.

The people on the third floor call themselves bards. They seem much less concerned with the societal structure built up on floors one and two, instead having their own stratification. At first, the bards seem content to while away their days in their garden home with art and culture, their language having words for agora, theatre and windmill. But after a while it becomes clear that there is an underclass of blue-masked bards, referred to exclusively with the word for idiot.

The linguistic and cultural divisions of the tower are obvious and key, but scattered two to a floor are computer terminals. Some of these terminals show two of the groups trying to talk to one another. Once you’ve been to the top and learned the truth of the world, that the tower is held deliberately apart by a program called Exile, you can descend down again and provide translations. Not only are you facilitating speaking to one another, but each group is asking for help that only another group can provide.

Most European languages, including English, and several Asian ones, are descendants of Proto-Indo-European. This language was spoken maybe 6000 or so years ago, most likely in the region of the Black Sea. By comparing the vocabularies of languages as far apart as Hindi and Irish, it’s been possible to reconstitute a large portion of Proto-Indo-European, and therefore find out what kind of words they had. For example, since words like vader (Dutch), padre (Spanish and Italian), pater (Latin), pitár (Sanskrit) and father all follow established patterns of linguistic shift in their respective languages, it’s possible to say that they must have a common root. In the case of English and Dutch, that root is Old German, but to account for the Romance languages, and ancient languages like Latin and Sanskrit, the root must go back further.

Thousands of these examples make up Proto-Indo-European. It might not be surprising that they had a word for father, given how human reproduction works. But what about *dy?us ph?t?r?

Reconstructed Proto-Indo-European has a lot of hedges on both accuracy and pronunciation, which show up as the various diacritics here. But read this as you might without the accents – Dius Fater – and you can already see where these roots have found themselves in modern English as well as other languages. Deity, from the still-familiar Latin Deus is a clear connection. So too is Zeus Pater, as in the father of the Greek gods, and the Sanskrit sky god Dyáu? Pit??. We know, based on language reconstruction as well as cultural continuation, that the group of people who spoke Proto-Indo-European worshipped a sky god.

In the same way, we can build a picture of the entire culture, despite it leaving no written record. We know that they had archery, poets, livestock and a reciprocal gift-based economy. They span, weaved, made beer and kept dogs.

The groups in Chants of Sennaar are separated. The true ending of the game requires fixing this by translating the requests on the computer terminals. To do that, you have to find the concepts that the groups share among all their differences.

The alchemists and the devotees both have a word for plant – and the devotees needs help restoring their dying garden. The warriors learn that the devotees can’t be “impure”, because they both love music, and they invite both the devotees and the bards to perform in the fortress.

The alchemists ask for help with the monster, saying they’re afraid to do it themselves; the warriors respond that they have no fear (and yet, notably, they have a word for it). The devotees offer freedom at the abbey to the underclass of the bards, and the alchemists offer them brotherhood.

(One stumble in Chants of Sennaar’s otherwise deeply thoughtful borrowing from real linguistics: it is specifically translated as brotherhood, which is strange in a setting where the characters have no apparent gender. Nor is this the only example. One of the first words you learn is “person”, but the game translates it as the clumsy “man/human.” There is no indication that this fits within the world of the game since, again, no gendered hierarchies are ever alluded to outside of these words. Lamps in videogames use real electricity; languages in videogames use real patriarchal conventions.

Chants of Sennaar’s world is pieced together from bits of ours that make our understanding of it slot together piece by piece. The connections between its cultures are, to varying degrees of abstraction: care, art, bravery, freedom and allyship. We could do worse as a foundation.

———

Jay Castello is a freelance writer covering games and internet culture. If they’re not down a research rabbit hole you’ll probably find them taking bad photographs in the woods.