Status Ailment Era

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #182. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Analyzing the digital and analog feedback loop.

———

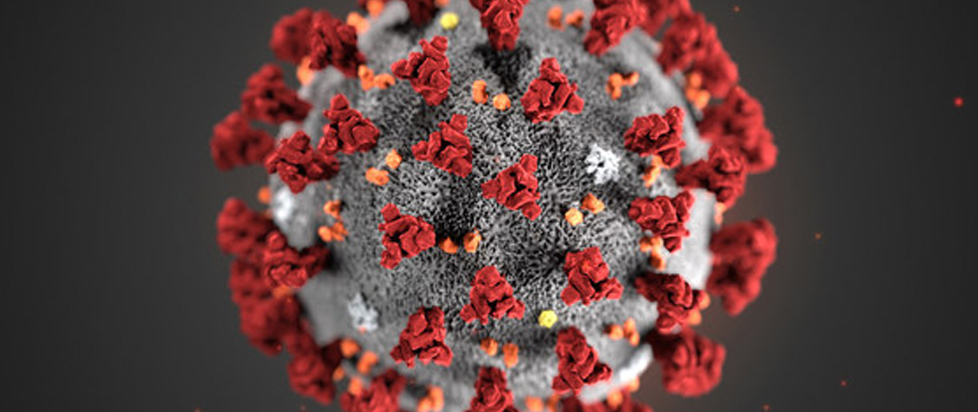

October of this year was the first time I tested positive for COVID-19. I was very lucky to have only caught it once and that it was a milder variant. While I don’t have long COVID or a serious set of post-illness disabilities, I know of people who do. Their conditions often have comorbidities and are subject to medical systems that are slow to adapt to people like them with complex disabilities. Any who don’t neatly fall into known or accepted categories of diagnoses or treatment often face stigmatization or are dismissed outright. As I drifted in and out of states of fatigue that are often triggered not even by physical exertion but the simple process of thinking during my post-COVID months, it struck me that we are all dealing with the effects of an era that assumes that all ailments are temporary and able to be purified eventually.

A lot of RPGs include not just the perils of dying but status ailments – conditions of illness or general unwellness in the midst of battle. Or sometimes such ailments can be caused by unfortunate interactions with a toxic or precarious environment. One can be poisoned, which saps at your health points over time. You can be paralyzed by your agitated nervous system or completely petrified. Regarding the latter, you can take that literally or figuratively as well, with some RPGs turning you into stone Medusa-style or stymied by primal fear. You can be blinded or made mute. As a related aside, I’ve always been fascinated by how speech is tied to magic, especially in the Final Fantasy series. Equally as fascinating is the vagueness of treatments for status ailments like silence. The cure for that status ailment of silence is using (consuming?) an item called an “Echo Screen”, which I could never quite picture mentally.

In fact, all the ailments that are more abstract and temporal like confusion or berserk are equally as mystifying. They suggest that such emotional and cognitive states can be easily corrected via medication, which I suppose might say something about the medical zeitgeist of the Final Fantasy series and other RPGs possessing similar systems.

There are probably many more ailments I could list, but what is important to note about all the above is that they are often classified as temporary. They are also relegated in most instances to a mostly non-diegetic space within RPGs. Unless the story calls for one character to be poisoned by a uniquely virulent toxin or struck by some other ailment (in FFIX, for instance, Princess Garnet temporarily becomes mute due to retraumatization), status ailments are not acknowledged outside of battle screens. Cloud Strife’s Mako poisoning and resultant mental distress from that experience is positioned similarly to Garnet’s predicament. Both also eventually recover due to some mix of persistence and the care of their friends and loved ones. This could be taken as morally trite if one leans cynical, or hopeful when we consider that mental health issues are often in need of a healthy support network. One that doesn’t just view the distressed as medical cases to be solved or clients to be served.

To briefly clarify, I’m not saying either of these above examples are explicitly status ailments. Neither game’s system acknowledged their protagonists’ conditions as such. I believe it would’ve been interesting, however, if FFIX and VII utilized status ailments as a ludonarrative tool. Both for continuity’s sake and for emphasizing these major story events via their classic RPG mechanics. I’m a sucker for this kind of holistic storytelling.

COVID-19 and long COVID are ailments which our societal leaders insist are temporary or effectively controlled by new medicines, similar to how RPGs treat status ailments. But the reality is that it’s an illness that varies wildly from person to person. I believe in vaccines, of course, they are what allowed my recovery to be relatively swift and lessened symptoms which could’ve been detrimental to me without. But we lack robust systems and philosophies of care that help our pandemic ravaged world adapt to populations who have been disabled and, in some instances, made chronically ill on a scale not previously seen in medical history. This realization, for those doctors resistant to it, is not new either. Disabilities, chronic conditions and illnesses are inconvenient for late-stage capitalist and imperialist paradigms (but what about the productivity??). And illness in general has always been spun into myriads of metaphors, usually moralistic in nature.

Susan Sontag wrote extensively on how illness is constructed metaphorically with her works Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and its Metaphors. She covered the most stigmatized of diseases throughout the ages, namely tuberculosis, cancer and AIDS. All those mentioned have had such a powerful hold on society that these metaphors were taken not just as facts of the illnesses, but symptomatic of character defects in individuals who suffered and died from them. The moral narrativization of illness is still deeply rooted in North American and European societies. Sontag states this is due in part to religious beliefs of diseases and ailments being deserved punishments for sinful behavior. But this sort of thinking wasn’t isolated to religious people – the secular world adopted these beliefs as well, mistakenly rationalizing them as markers of excesses of the body or mind. In the case of AIDS, for instance, Sontag noted in the ’80s how there was a worrying increase in the militarization of language used around the disease. The transmission and infection of this disease was characterized as a problematic foreign invasion of the body.

Megan O’Rourke picks up this thread in particular with her book The Invisible Kingdom: Reimagining Chronic Illness. She’s concerned about the stigmatization that prevents those living with chronic illness from even getting diagnoses or courses of treatment that improve quality of life instead of fixating on perfect cures. O’Rourke refers to this state of affairs as a silent epidemic, one that’s been exacerbated by COVID-19, but that existed long before that. Since graduating from university, she became increasingly aware of a chronic illness which she may have had for a while. But it took years for her to reach a diagnosis, due to medical skepticism. There’s still a sense that your character is bound up in how healthy you are. It’s part of why the public was so shocked at how best-selling author and scholar Madeline Miller had been deeply affected by long COVID. To the point that it garnered multiple profiles on her experience to raise awareness about the condition.

Discussions of status ailments in games tend to focus on whether or not they are effective as a mechanical challenge, as this one Reddit user outlines. Ailments and such elements of RPGs are often not looked at metaphorically and on one level you could say this is due to the fact that we usually experience them with the lens of escapism. I for one, didn’t think about status ailments in games as a cultural metaphor for years, except maybe to laugh at how easily cured they were. Final Fantasy often features a cure-all item like Remedy, as well, which in real life we’d probably scoff at as snake oil.

Do status ailments and their treatments in games perpetuate toxic mythology about diseases and disabilities? I don’t have an answer to this, nor can my post-COVID brain formulate much conjecture about the matter yet. But my gut instinct says that in some cases, even if unintentionally, they do. We still grapple with a deeply entrenched thanatophobia, especially in Global North societies, of which Japan is considered a part. But any culture which fixates on the potential for immortality is probably guilty of such mythologizing. I mean these are matters of the human condition, after all.

Lately, I keep thinking about how games are often synonymous with agency and empowerment. And how the games industry is often ableist and often forces marginalized developers to internalize the idea that they “have to be built differently to stay resilient”. I’ll be frank about my status ailments post-COVID – so far I can identify silence, often induced by fatigue and confusion. I’m definitely built differently now, but not necessarily with regard to resilience in the traditional sense. As I muddle my way through the remainder of this year, I might return to this if these ailments lessen. There are a lot of mechanics in games we take for granted, symbolically. And to end with a paraphrase of a quote that particularly resonated with me from Sontag’s thesis, my point is that status ailments in RPGs (and their rough equivalents in reality) are not metaphors. Or at least, unlike the diseases Sontag discusses, they are perhaps not consciously constructed as metaphors. We should be aware of what they can signify about our cultural perceptions around health and wellness, regardless.

———

Phoenix Simms is a writer and indie narrative designer from Atlantic Canada. You can lure her out of hibernation during the winter with rare McKillip novels, Japanese stationery goods, and ornate cupcakes.