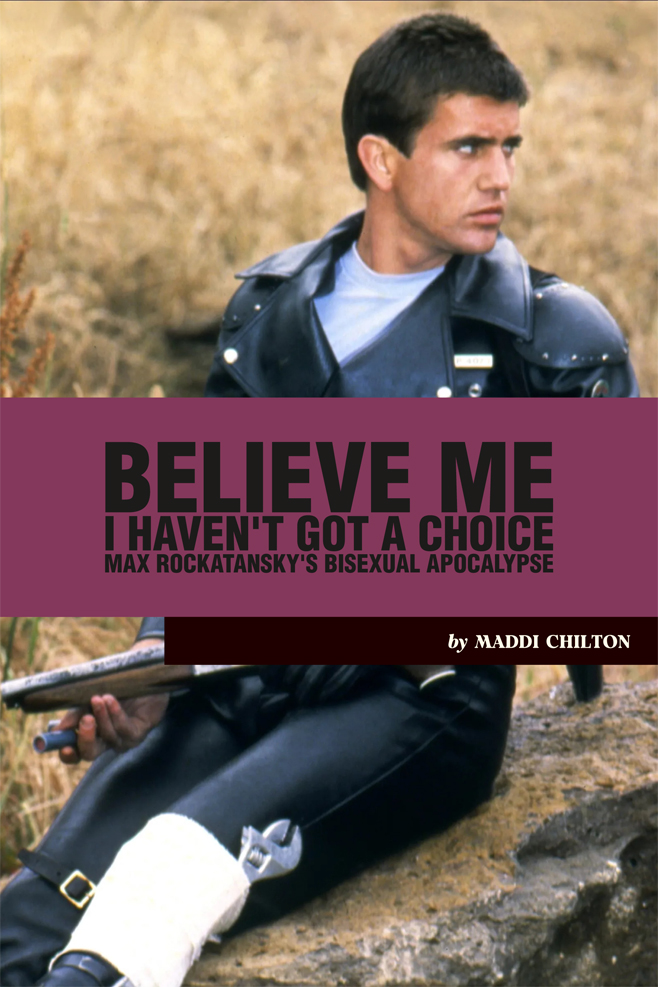

Believe Me, I Haven’t Got a Choice: Max Rockatansky’s Bisexual Apocalypse

This is a feature excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly #181. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Watching Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior for the first time in 2024 is a deeply disconcerting experience. In the near-45 years since, the landscape of dystopian media has been populated with endless derivatives, trying to match George Miller’s lean, violent masterpiece, the Platonic ideal of cool man wears leather, drives fast car. It evokes an intense sensation of deja vu. The aesthetic of The Road Warrior’s wasteland lives beyond itself. You mean this is where it all came from: the black leather, the chains, the masks? The wild, flamboyant aggression, the roaring engines, the anarchic command of the desolate end times? There have been endless iterations on the theme since The Road Warrior came out in 1981, but none of them have managed to do what Miller did with such confidence and style.

It’s also striking what has been left out by subsequent shameless attempts at mimicry. The post-apocalypse, in the years since, has become heterosexually macho, the stomping ground of manly men in gray clothes with big guns: in The Road Warrior it was instead a playground for harnesses, assless chaps, and men leashed to other men. From the first moment that Max makes eye contact with Wez, the most prominent biker in the film, and the beautiful young man he keeps chained to the back of his bike, the film establishes itself as not just homoerotic (as might be expected from any male-dominated movie) but textually homosexual. The theme arose coincidentally mid-production: Wez’s companion was changed from female to male to emphasize the lack of conventional gender roles in the post-apocalypse, but the BDSM biker gear was an unrelated stroke of brilliance from their costume designer, who walked past a local dungeon every day on her way to work. Once the theme was established, though, Miller leaned into it, to the extent that one of the marauder factions is simply called “Gayboy Berserkers.” The layered, transgressive power dynamics of the biker gangs are best shown by the progression of Wez’ character as first the dominant partner of the submissive Golden Youth and then the semi-coerced submissive of Lord Humungus himself, who displays Wez proudly leashed to the hood of his war machine in the final sequence. The apocalyptic wasteland, in The Road Warrior, is the domain of outlaw sexuality, a rejection of traditional sexual and gender dynamics with a healthy side of danger and violence.

The plot of The Road Warrior is simple enough. An isolated community of settlers with a working oil refinery are surrounded on all sides by biker gangs and marauders, led by Lord Humungus, who wants their gasoline. Max, like all wasteland wanderers, is also looking for gas, and he strikes a deal with the settlers to help them source a prime mover to pull their tanker and escape to the coast in exchange for gas for himself. Plot ensues; chaos happens; the deals Max makes go from voluntary to less voluntary, and the whole scheme ends with a massive and thrilling chase sequence. The settler community wears only white, includes children and elderly people, and is represented primarily through noble warriors and the practical, assertive patriarch Pappagallo – a dramatic difference from Humungus’ black-clad army of berserkers, human traffickers and bloodthirsty drivers. The tension between these two warring societies is the key conflict of the film, and the dichotomy between them couldn’t be clearer: the settlers at the oil refinery are representatives of the dead world, traditional family structure, and societal order, and the marauding bandits outside their gates represent the brave new world of transgressive sexuality, nontraditional power dynamics and violence. The endless siege of Humungus’ troops against the traditionalist enclave makes literal the right-wing talking point of homosexual incursion upon heterosexual lifestyles, and of the ill-intent and assumed violence brought with them.

And then there’s Max, existing outside. His introduction involves him outwitting the bikers at their own game, introducing his film-long and homoerotically charged rivalry with Wez; he drives a fast car and wears black leather, stealing and scavenging, occasionally killing (indirectly) and kidnapping (directly) to serve his endless hunt for gasoline. He lives in the world of the bikers and does a very good job at it, but he never becomes integrated with their society or with that of the settlers. His character is fundamentally isolationist. More than anything, Max Rockatansky wants to be alone. This is often attributed to an inability to engage with society on any real level due to past trauma, but that’s not borne out through the text: Max is repeatedly shown to be an emotionally attuned, capable character who has to ignore this sensitivity to stay alive. Max’s aloneness is instead a political choice, a deliberate stance amidst the binary of the wasteland, to participate in neither the resurrected corpse of pre-crash heterosexual society nor the flamboyant new age of apocalyptic queerness.

Max’s balancing act is a maturation of his conflict in the first movie. Before the world ended, Max Rockatansky was a Main Force Patrol officer: a cop, clad in the film’s blatantly fetishistic black leather outfits, whose job was to run down the marauding biker gangs that ran rampant in shortly-pre-apocalyptic Australia. The first movie’s Max spends the majority of the film torn between a job he excels at that he feels is a danger to his humanity, and his idyllic home life with his wife and young child. On one side, he has a personal life he treasures, in which he’s able to be vulnerable and emotionally open; on the other side, he has an unmitigated talent for vehicular violence, which makes him a coveted asset for the stretched ranks of the MFP. Max, wavering in his loyalty, is first lured back to work by the souped-up V8 Interceptor and later bullied out of what is textually not his first resignation by his leather daddy police chief (whose authoritarian homoeroticism warrants its own article). Cue the revenge movie hallmarks: the bikers kill his wife and kid, he kills the bikers, and he drives off into the sunset, bloody and hurt and alone, clad in black.

The first movie shows a man torn between two different worlds, weighing and navigating his participation in both. The second movie codifies these worlds even as its protagonist removes himself from them. Max’s psychological upset, the core of his internal controversy, is not that he cannot be a part of the world-that-was, a heterosexual culture of law and order, or the world-that-is, a violent culture of transgressive queerness, but that he is part of both. A binary is by nature exclusionary; an attempt to participate fully in one inherently negates the other. Max’s turmoil in the first movie is of this negation, of his inability to understand himself as one person when held between the leather-clad MFP and his gentle home life. Max’s quiet and stillness in the second movie is because he has come to the understanding that he is both, and that because of that paradox, he can never be either. So, he lives alone, roving with his dog, a voluntary outcast, the only space in which he can be fully honest.

There it is: the paradox of the bisexual. Isn’t that the eternal tension of the whole scheme: how can one person be two different things? The world is becoming more progressive, but the binary upon which heterosexual society has built itself is still very strong. As long as the assumption of monogamy is intact, it’s an unfortunate truth that the bisexual person will never appear, beyond temporary cultural stereotyping, to be actively bisexual: society will see them as gay or straight based on their partner, their actions or their appearance. It’s a game of perceptions. On the one hand, this gives the bisexual person a practical advantage, as they can essentially appear to belong anywhere, moving seamlessly between heterosexual and homosexual society based on what elements of their life they choose to hide or show. On the other hand, this means that the bisexual person never truly belongs in either world. That self-denial, that negation, can be stomached by some, but for others it’s an unacceptable barrier to living their true life, an ask that asks too much.

———

Maddi Chilton is an internet artifact from St. Louis, Missouri. Follow her on Twitter @allpalaces.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 181.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!