Losing Christina

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #180. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Elsewhere, here.

———

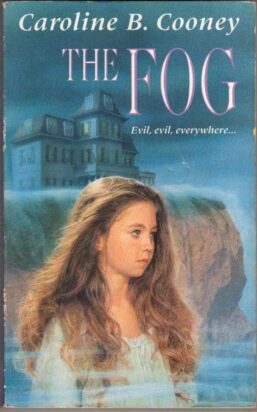

There is nothing supernatural in The Fog, the 1989 teen-horror novel by Caroline B. Cooney, although it seems at first as though there might be. Christina Romney is on the boat from her home island to the mainland, where she will board for the school year. The tourists on board are fascinated by the beauty of the island girls, and call them princesses: “Sent away for the sake of the islanders . . . to be given to the sea.” Christina’s friend Anya, the most beautiful and intelligent girl in Maine, believes that the sea wants them. Eerie, but misleading. Set in Maine with a cast of abusive authority figures, children who see the truth and the children who bully them for it, The Fog, sounds like a Steven King knockoff for children, but while to the islanders the sea has an outsized, almost supernatural presence, the horror of this book remains stubbornly, terrifyingly, mundane.

The danger in this book comes from local authority, and small-town systems of power. While the country – along with our own Mayor – stokes fears about the safety of my home-turf in NYC in order to fund their law enforcement agenda, I’m far more nervous outside of my garbage strewn, rat infested radius. When I was still pregnant, I refused – for my health and safety – to go to any state with abortion restrictions, which made me unable to go road-tripping with my mother and sister. There are parts of my own island I won’t visit because they’ve enacted mask bans. My city’s police force is the thing I find most frightening here. There is danger in those who seek power through official channels, but an unruly place like New York can fight against them. It is, perhaps, harder in a small town.

The island children board with the Shevvingtons, and they are evil. There is no explanation for how they came to be this way, and there is no motivation other than a sick conspiratorial joy that the married couple has in taking the brightest, nicest girls and depleting them of their spirit and their ambition. The randomness of their evil is what makes it truly terrifying. “Who is this woman, that she wants to get at me?” Christina wonders. “Who am I to her?” The Fog is a novel about gaslighting, although that term is never used. While Christina immediately recognizes the cruelty of the adults she has been trusted to, the Shevvingtons are respected and beloved authority figures. The sea is dangerous, but it takes without malice. Evil lives in the institutions of man.

Christina’s crossing to the mainland creates a reverse fairy-tale, in which children leave the safety of wildness to explore the deep, dark heart of small-town life. Before leaving, Christina dreams of junior high as an opportunity for adventures her wild island is too small to contain: “She wanted love, adventure, and wild, fierce emotions that would batter her, as storms battered the island.” It could be the opening song of a Disney Princess movie except that instead of venturing into the unknown Christina’s new horizon is: “a school with classrooms, a cafeteria, hallways, bells that rant, art, music, gym, and hundreds of kids.” And while the deep-dark-woods of fairy tales have dangers that amplify their particular psychological place in the literary landscape, this small town has the Shevvingtons, who are in positions of power in Christina’s bright new world.

Mr. Shevvinton is the school principal, and Mrs. Shevvington teaches English. Their power comes local systems of authority and discipline, suggesting that these places are a natural home for evil in the same way that the woods are the natural home for gingerbread houses. They are allied with the school’s mental health counselor. They live in a town with a street that bears their name and a historic restaurant, and a collection in the local maritime museum. Not just the authority of their positions but the old, entrenched authority of whiteness and money. “They told The Truth,” Christina recognizes, while she only has truth in its lowercase wild unauthoritative form.

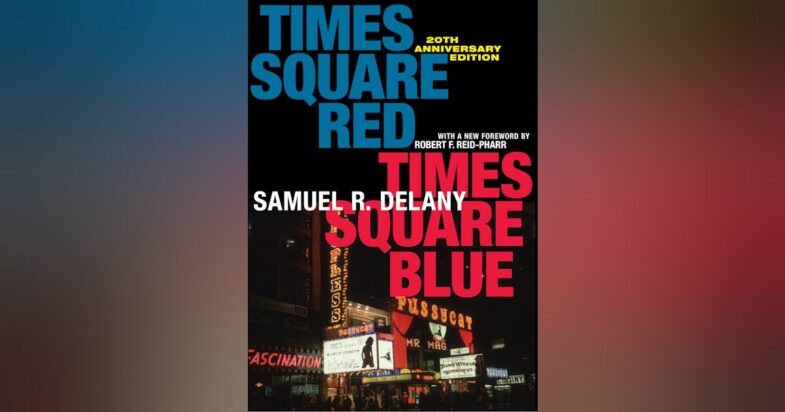

In Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, Samuel R. Delany writes about the “structure of violence in small towns.” He argues that it is not less prevalent in those places than it is in big cities, but that it is less random. “People know where it’s going to occur and in which social units.” This structure encourages residents to integrate themselves into the authoritative structures of the community, because having the knowledge of where the violence is can keep you safe from it. “They know how to stay out of its way. Your biggest protection from the rest of it is that you’re not a stranger to the place.” Christina, who is a stranger to this place, finds that her appeals to insiders can only go so far. The children who believe her have no power in the small-town authority structure, and the adults who believe her are themselves too embedded in the structure to see its rot like she can: “Grown-ups can only tolerate half the truth.”

Christina is an obstacle to the Shevvington’s, but she is too unruly to be their target, too much of the island. Anya, poor, dreaming of getting even further from the island and becoming a doctor in a big city, is who they really want to ruin. They do this by stoking Anya’s fear of the sea – the wildness she comes from – gaslighting her with pieces of seaweed in her room, and noises, and wetness, until she is so sure the water is coming to get her that she drops out of school to work in a laundromat where all the water is locked safely behind glass windows. By convincing her that evil is wild and natural, she is unable to see that it is coming from the ordered, constructed world that she yearns to belong to, and in a terrible irony she is removed from its center and sent to the margins as a result.

“Mrs. Shevvington has more power than me.” Christina muses. “But what is the power for? Where are we going with it?” Power, for people like the Shevvingtons, is just to maintain power. There is no real ideology but just the authority they need to be cruel without repercussion. Christina is safe from the Shevvingtons, ultimately, because she refuses assimilate into small-town life at the cost of her love for the wild island she comes from. Because of that she cannot be convinced that she is crazy or weak. She faces down the sea, which she knows is not evil or good but simply is, rescues Anya from drowning and faces down the Shevvingtons.

It should be a triumph, but: “She was only a seventh-grader.” the book reminds us after Christina’s victory. “She knew nothing. She did not know that people do not surrender power so easily. Christina thought she had won.” Cooney knows that evil powers that have affixed themselves to systems of authority are more difficult to definitively defeat than a witch in the woods. A few children cannot push them into an oven and be done with it. The adults must be willing to see the monsters too.

———

Natasha Ochshorn is a PhD Candidate in English at CUNY, writing on fantasy texts and environmental grief. She’s lived in Brooklyn her whole life and makes music as Bunny Petite. Follow her Twitter, Instagram and Bluesky.