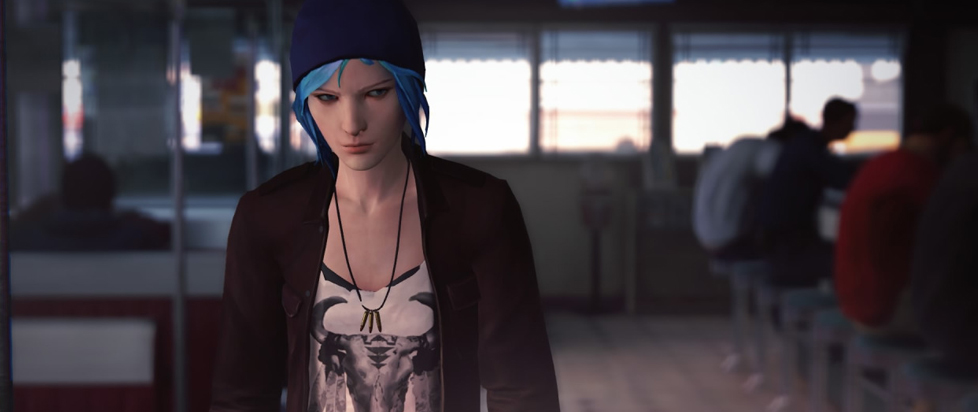

The Forgotten from Disney Dreamlight Valley

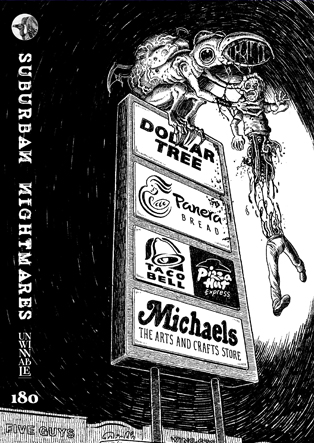

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #180. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Fictional companions and goth concerns.

———

Disney Dreamlight Valley is a game about building a suburb. Granted, the setting is a mystical valley containing oceans, forests, plateaus and frozen areas (guess who lives there). But as the game progresses, you build more and more dwellings to lure more and more Disney characters into the valley, thus creating, in essence, a suburb.

That doesn’t sound very horrific, unless you are horrified by cozy games and/or Disney propaganda (many are). But hear me out.

The narrative premise of Dreamlight Valley is that you, an adult, leave city life to return to “a familiar place,” then fall asleep in the woods and awaken in a magical valley where you hung out as a child. Disney and Pixar characters used to live there, but an event called The Forgetting caused them to lose all memories of their time in said valley. You and Merlin – his memory’s fine – must work together to bring everyone back and restore their memories.

During the game’s opening act, you hear rumors and catch glimpses of a “Dark Entity” (Donald Duck’s words). This entity, it turns out, is a personification of your abandoned inner child – a part of you that felt forsaken and splintered off when you stopped returning to Dreamlight Valley. An apt metaphor.

This is suburban horror: the daily grind of forgetting oneself, losing oneself.

In real life, abandoning one’s inner child is slightly more nuanced than abandoning an empire of officially licensed characters (at least, I think it is? I’m not a mental health professional). John Bradshaw, the counselor who popularized the term “inner child,” argued that that until “they learned to seek out and heal the hurt child within . . . most adults stumbled through life, expressing their pain through self-destructive behavior.” In the process of growing up, most of us, at some point, struggle with disconnection from the interiority of our childhoods. Hopefully, we return to that inner child in one way or another (I’ve never read Bradshaw’s work, but I’ve found therapy and witchcraft very helpful).

After the reveal that The Forgotten is part of you, the game offers a content warning: “The Forgotten Memories Quests deal with some difficult emotions and themes, such as sadness, loneliness, and anger. If you’re not in the right space to deal with these themes, consider returning to your Village until you feel prepared to face them.” While it’s easy to cringe at anything Disney does, I appreciate this gentle acknowledgment that doing inner child work and shadow work kind of . . . sucks. Even for fictional characters. We’re not always going to be in the right space to handle that.

If you successfully heal your relationship with The Forgotten by talking to them about the nature of childhood, adulthood and play, you can convince The Forgotten to move back to the valley and live a peaceful life. The Forgotten asks for some time alone to “process,” and you’re both free to live your parallel lives.

Part of me likes the idea that, if we don’t do some kind of inner work eventually, a shadow entity whose clothing mirrors our own – but more goth – will haunt us until we acknowledge them directly. This could also be a metaphor about the body keeping the score. But instead of the body, the score is kept by a personified shadow with glowing green eyes.

Dreamlight Valley is a cozy game, far removed from the horror genre. But the literal version of its shadow self-scenario? That’s a solid horror movie.

———

Deirdre Coyle is a goth living in the woods. Find her at deirdrecoyle.com or on Twitter @deirdrekoala.