Dream Vacation

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #180. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

What’s left when we’ve moved on.

———

In season one, episode ten of Sex and the City, “The Baby Shower,” Carrie et al go to a Connecticut suburb to see their friend Laney. Four childless women, they drive into the driveway of a house that, it will soon be revealed, is filled practically floor to ceiling with moms. If you’ve ever heard anything about Sex and the City, you might be prepared for the various divides this episode is about to explore between urban/suburban, wed/single and rich/slightly less rich.

What you probably wouldn’t be prepared for is that “The Baby Shower” is shot like a horror movie. Carrie spends the whole party walking around while mommies blur on all sides of her like melting monsters. One of the moms has an Oedipal relationship with her son, another is permanently high. The main mom who the shower is being thrown for used to be a partier and is now pregnant and sad, stuck in her huge house. When she tries to come back to New York, it vomits her back up. Even though the episode is supposed to be about the main cast deciding whether they want children, underneath the A-plot something is wrong.

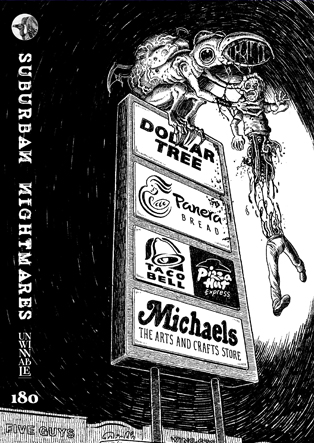

In 1985, Don Delillo’s book White Noise envisioned the burden of living in American sameness as a literal toxic cloud. This summer Chapell Roan released an album about compulsory heterosexuality set partially in the suburbs, including in contrast songs set in New York and L.A. (and where else other than the suburbs has anyone ever seen a Papa John’s.) The suburbs are conformity, and they’re also, for people around Roan’s age or a bit older, parenthood.

Sheila Heti’s book Motherhood revolves around a series of coin flips, which the narrator makes every time she’s faced with a question. This is a metaphor for the question she’s trying to answer throughout the book of whether or not to have kids. Maybe it’s because I know the outcome already – she doesn’t – but I found this device so irritating that I’ve only made it fifty pages into the book. Another irritating thing is that the book assumes that the question of whether to have children is equally as important to its readers as it is to the narrator, who, its jacket states, has “reached an age when most of her peers are asking themselves when they will become mothers”, thereby making her exceptional and, one would think, interesting (as is probably clear, I think one would be wrong).

Heti’s narrator’s husband says to her (within those fifty pages) “I don’t agree with those values you come back from New York with.” They lie in their bed that, wherever it is, is made suburban by not being in New York. In Miranda July’s book All Fours, the main character is also trying to get to New York, but she doesn’t go there. Instead, she makes the inverse journey of the cast of Sex and the City, going from suburb to rural. She stays in a rundown motel, falls in love with a married car rental salesman, and loses her shit while lying about actually being in New York. Here the suburbs are what’s between what she should want (New York) and her new dream (two weeks in this motel). She has a kid already, back in the suburbs. Her story is about how to escape them – and by extension: middle age, marriage, heterosexuality – by creating a dream life with her bare hands.

One reason I like All Fours more than Motherhood is because it doesn’t indulge in the significance of the “most important question” of a woman’s life. The choice has already been made; the bargain has been drawn. Like mothers on Reddit who confess privately that though they love their kids, they would have made a different choice if they knew how it would be, she regrets her life even as she admits the stability it provides is the main reason she can have a little fun. It’s also funny that both Heti’s and July’s narrators are writing books, and neither is getting them written. Book is a substitute for baby (or lack of baby).

I’m susceptible to the horror shots in “The Baby Shower” on several levels. First, I’ve never lived in the suburbs, having lived in rural areas for my childhood and so far in cities in my adulthood. In both cases, the areas I’ve lived in have been so aggressively anti-suburb, and the media I’ve consumed has been as well. White Noise is somewhat responsible for my image of midsize American towns as oppressive. Delillo was the first author to win the Jerusalem Prize for work that represents the freedom of the individual in society, and the suburb as a toxic cloud surely shows that interest in his writing. White Noise is a satire that turns into horror, much like “The Baby Shower.” Both are interested, in different ways, in death and chemical attempts to deny its reality.

Sex and the City is a little more unsubtle about it (this is, after all, the show that compared being single to being Catholic in 1990s Northern Ireland). The episode concludes when Carrie sits in a playground and watches a young girl playing, then, on the walk home, gets her period. This isn’t an episode with anything to say about death, freedom or motherhood on purpose. Its greatest thesis can be boiled down to “isn’t it sad when hot young people get old and gross?” yet the things Laney has – a baby, and moreover a big, beautiful house – are exactly the things the show’s main characters drool over, except they’re in the wrong physical location. The suburbs turn them from enviable into scary and embarrassing.

Yet it’s what the show says about motherhood by accident that I find more interesting. Motherhood is a death of the self: rather than a book, it’s a grave. The confines of the show and every conversation in this episode bring even the characters who are skeptical about being parents around on the issue (Miranda, who is the most grossed out by parenthood, ends up having kids, where the playground-lingering Carrie never does). Meanwhile, Laney makes her first and last appearance in the show here. She’s as good as dead.

Most of the famous horror about motherhood is really about childbirth. But this horror about suburban motherhood makes the experience more generalized, if less gory; not everyone is afraid of pregnancy, but everyone is afraid of being controlled. July’s narrator in All Fours finds that when she’s on vacation, real life “sounded so foreign to me, like a parody of a life,” an echo of a line in White Noise: “People take vacations . . . to escape the death that exists in routine things.” “The Baby Shower” horrifies because it shows that parody becoming real life, from which there can be only a temporary vacation. It’s an example of a lasting fear that’s still breaking through into pop culture (Nightbitch, for example, is coming out this December) and that suburbs are a physical site of the gender roles that suffocate women and stalk them for their entire lives, It Follows style. The power of the suburbs to turn desire into horror still fascinates, and we’re still trying to find out how to deal with it.

———

Emily Price is a freelance writer and PhD candidate in literature based in Brooklyn, NY.