A Dismal Tide: The Rover’s Neo-Western Nature

There is no shade in David Michôd’s Australian neo-western The Rover, the sun having burned away whatever forces once held this world together. Beneath this eye of fire, men with guns and vendettas roam the lawless land. Released in 2014 alongside a political climate of hopeful status quo and superhero industrial complex domination, the film follows two men on a simple quest to retrieve a stolen car. Their path leads to the violent, tragic endpoint that is rugged individualism masculinity. This dour nature resulted in muted critical response and a box office return less than half its budget, subsequently becoming something of a forgotten footnote within the A24 catalog. Now ten years on, the world older and changed in innumerable ways, I find The Rover’s evisceration of traditional Westerns inescapable, the film’s soundtrack playing at the back of my mind as I commute along flatland highways where war-ready pickup trucks follow too close and far away grass fires turn the sky nicotine brown.

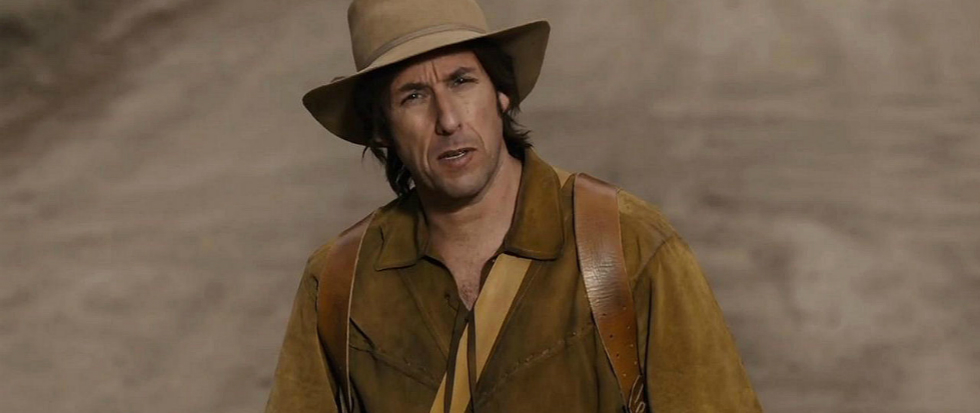

Taking place in the wake of a near-future economic collapse, the central Australian Outback stretches unto the horizon line heat mirage. All that the camera puts its eye to is a slight patina-green, a welcome change from so many apocalyptic browns and grays. Whatever opportunity there was in this West has long since dried up, as evident by iconography such as mining scars traced across the earth’s surface or the remains of a circus in a land without children. It is in a ramshackle bar that Eric (Guy Pearce) has come to rest, his face emotionless and weathered. Outside the window, a car goes sliding by on its top in a shower of dust and sparks. On the run from a botched job, its criminal occupants wind up stealing Eric’s car. He will spend the rest of the movie in pursuit, the car seemingly his last possession of any importance.

Always dependable, The Rover is an all too rare turn for Pearce in a leading role. Calling to mind the similarly-toned The Proposition (2005), Eric is a man on a mission, enraged by what has been taken from him, but what makes the performance so rich is the quiver of vulnerability that bleeds through. Pearce undoes the cliché of archetypal male Western hero, dominant and violent, yes, but never glorified for it. Aspects of this broken world still catch on him like unexpected hangnails, painful signs that there’s still a pulse within. In one such moment, Eric discovers a room full of kenneled dogs who have been put up for the night, otherwise locals would hunt them for meat. His shield slips, eyes watering as he’s unable to speak for just a moment before recovering. This defense is soon dismantled by complications in his chase.

Left behind by the criminals is one of their own, Rey (Robert Pattinson), who stumbles upon Eric. Though never stated, Rey clearly has a learning disability and is easily coerced. With both him and his brother (Scoot McNairy) bearing American Southern accents, it’s easy to imagine them having been lured Down Under as blue-collar laborers by corporate promises of steady work, only to wind up stuck without a future. Pattinson’s performance arrives just two years after the final Twilight film, firmly driving a stake into public conception of what he could accomplish. In what could have easily been a Forest Gump-esque sidekick, Pattinson fills Rey with equal measures innocence and ignorance, a childlike chameleon who emulates the older men around him, unable to avoid reenacting their mistakes.

It isn’t long before Rey comes to treat Eric like a surrogate big brother, looking up like a loyal pet at the man who initially hauled him around at gunpoint. Rey is just a kid, he should be off goofing around. There are glimpses of that, such as an unexpected singalong to Keri Hilson’s “Pretty Girl Rock,” and they color everything with shades of tragedy as the gravity of violence comes to hang upon his neck. For Eric, what he initially viewed as a bargaining chip, ordered around with the flick of a pistol, turns into a glimpse backwards into what the world has moved on from. Small acts of vulnerability, of humanity remembering to be better than its base instincts, are few and far between in The Rover, flickering like small nighttime campfires that barely keep the darkness at bay. It is in these moments that composer Antony Partos’s main motif is revealed. Funereal in tone, it is like sand dunes being blown back from houses where families once lived. We hear it as we watch Pearce play Eric as a man terrified by this sensation of life, as though it’s a cruel trick played on him by this land.

The Rover’s version of the West is as wounded as Eric and Rey, from the aforementioned abandoned mines to the weather-worn outposts. It has been tamed to the point of sterility. Whatever tendrils of capitalism that had found value in this land have long since pulled back, leaving behind a wake of detritus. But the land is eternal, still capable of beauty within its simmering flatlands and royal purple dawns. Throughout the middle of the film, Michôd frames Rey and Eric against these vistas, highlighting their place in the grand scheme of things. Whereas the traditional Western would paint these figures as trailblazers, rugged and self-sustaining, these men are but motes of skin and rags. In no time at all, no one will remember what happened in this corner of the world, nor the violence of those who passed through on their way to retrieve a car. This impermanence renders the journey all the more haunting.

Any remaining semblance to Western mythos is put down by the film’s climax. When Eric finally reaches his car, he quietly sits there, his humanity a wound reopened as he weighs the option to just leave. The moment is broken as Rey, having fully assimilated all that Eric is, ushers him forward into violence. In the wake of what happens, as the film’s theme swells to a mournful gale, Eric sews himself shut again. The motif becomes minor at this act before he sets out to finish one last task.

Earlier, a character questioned Eric about what’s left in the world to get riled up about. In the final scene, he drives out into the wastes and recontextualizes the film. To reveal how would soften the blow for new viewers, but for Eric, what’s inside casts him as a character in a Greek tragedy, locked into an ouroboros cycle of erosion. There’s no power fantasy within the violence used to reach his goal, no profit to be gained by living like this. Rey did not glean any life lessons before Eric rode towards the horizon, nor did Eric become a new man. The world within The Rover is fictional but dangerously close to a mirror, these men unable to do anything beyond add to the ruin around them.

———

Wyeth Leslie is a writer interested in pop culture, technology, and beautiful mundane lives. He is the author of the sci-fi hued poetry collection, This Machine Keeps the Ghost, from Alien Buddha Press. More of his writings can be found on Letterboxd as well as his personal substack, You Were A Kindness.