Was Colonial Marines Really Nuked From The Start?

This is a feature excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly #179. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Nobody sets out to make a bad game, especially not one as infamous as Aliens: Colonial Marines. Thanks to preservationists and a few candid (under anonymity) developers, it’s become clear how close it came to being something special. “It was very tumultuous for most people involved, but at the same time, I don’t want to blame any one person,” one developer emphasizes. “I assume that most of the people who had worked on it a decade ago are doing a lot better.”

It had the right team, engine and fantastic ideas. TimeGate’s efforts in particular with the campaign weren’t thwarted by a threat from beyond, but relatable realities of mismanagement and shifting goals. For TimeGate, a rough development cycle wasn’t anything new. They’d navigated the unique hurdles of F.E.A.R. expansions and launched their own IP, Section 8, a full AA-tier FPS. “It was very tricky, ‘cause there were some unique mechanics, like dropping from space.”

A senior developer recalls, “It was a very ambitious title for a studio that had never done their own original shooter, or worked in Unreal Engine before.” Yet through the process, they learned, and solid sales led to a sequel, Section 8: Prejudice. Prejudice went smoothly, teaching a crucial appreciation for the limits of console hardware. This would prove a painful irony.

TimeGate had already been in talks with Gearbox about assisting on Borderlands, so they made a perfect fit for the upcoming Aliens FPS. At the time, the scope discussed was akin to Section 8, according to a developer privy to the meeting details. It would be a tight budget, “We weren’t single A, but we certainly weren’t AAA. We weren’t spending 50 million or working with 200 plus people on a project. Section 8 was somewhere between 70 to 80 people over just under two years, out of a development budget of like 9-10 million.” This would keep things slim, but TimeGate was good with that.

At the time many peers had collapsed under bigger budgets while modest spending kept TimeGate afloat. “We’re like, okay, cool. We can do this. We’ll try to put out the best game that we can in hopes that it does well enough that it plays into a bigger, better sequel that we can also hopefully be a part of.” TimeGate went in expecting finished pre-production and set design – what they found was conceptual at best.

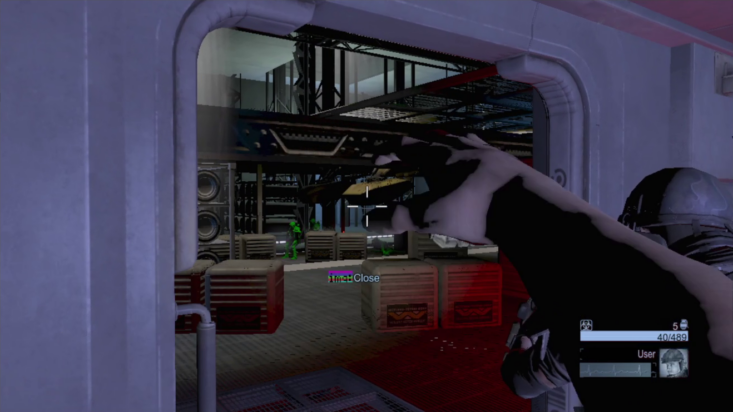

“Technology’s role in this is very important. The tech behind Colonial Marines was developed up to that point by Gearbox. They’d had the project and the IP for years before that, but they’d seemingly only done what we would’ve considered light pre-production.” Some environmental assets, the custom renderer and lighting, a test level with a simple xenomorph, marine, pulse rifle, and the initial groundwork for AI were all that greeted them.

“A lot of the assets they had built were over [polycount] budget; not within the constraints of what a PlayStation 3 could run. The vert count was catastrophically larger than what should’ve been allowed. For a small what-if sample? It looked cool, but had to be almost completely reverted. To call it a vertical slice or a First Playable would be wrong.”

Gearbox reportedly insisted the game was at First Playable, but regardless, TimeGate had to start from scratch. Having played one of the earliest 2011 builds, their consternation was understandable. Many prototypes are rough, but it’s clear how little they had to work from. “So we had to do all that core pre-production. That’s when it was clear. We looked at this project, we looked at the budget, we looked at the team size and were like, ‘This is going to be challenging’.”

The same could be said for the story, which would constantly evolve. The protagonist, Winters, started out as nothing but a voiceless audience insert. Much of the cast and the Xenomorphs were rapidly iterated. Most notably, a fully functioning albino Xenomorph variant called the Ravager was fully scripted and playable in test environments, only to be tossed. This became an alarming norm.

For instance, an entire set piece on the USS Sulaco was far enough along to have finished voice acting and partial animations before being cut. Winters and his squadmates would’ve rode a transport train sabotaged by Xenomorphs, crashing near their destination. It was in builds months before release, only to be nowhere in the final game. An entire introduction more akin to Aliens itself was also trimmed back substantially.

An enemy type might be introduced in one section, with polish applied, only for Gearbox to insist it be shifted to earlier or later in the campaign – repeatedly. The sentiment as development rolled on was that implementing the requested changes from Gearbox were more important than the purpose. The shift in priorities was in part spurred by Gearbox’s playtests with prototypes styled more after Brothers in Arms and Left 4 Dead that weren’t warmly received.

As a consequence, there would be an emphasis on prototyping ideas ripped from Call of Duty, despite developers at TimeGate reminding that this was supposed to be a horror shooter. Surprisingly, my sources pointed to Gearbox, not SEGA, as the party pushing these action elements in their experience. With challenges in vision and communication, the teams left to their own devices were the ones with happier stories to tell. Take for instance, lead artist Dave Flamburis for Demiurge, who was eager to speak on the record.

When talking with Flamburis, his experience is completely different. “As development unfolded, we became part of the multiplayer support resource pool,” he recalls. Having previously assisted with multiplayer in Brothers in Arms: Hell’s Highway, they were a natural fit. “Our dedicated team was quite small: myself, Tom, Chris, Evan, Jared. A quintessential strike team. We didn’t wear multiple hats, but we blended our skills. We worked as a holistic, turn-key dev team.” A handful of TimeGate staff also contributed to the multiplayer. Nerve Software would take point on multiplayer maps.

While TimeGate strived to satisfy shifting goals, the “entirety of the campaign content” was available to Demiurge, who worked uninterrupted. “A dream come true!” as Flamburis puts it, “We loved our isolation. Thrived in it. It allowed us to get lost in our work with zero dependencies.” Initially built for deathmatches, his team were eager to push beyond, as seen in the final game’s suite of modes. Despite their small teams, Demiurge and Nerve trucked along on the multiplayer.

Yet if one online component struggled, it was the campaign’s co-op mode. Due to a lack of clarity of what style of co-op Gearbox wanted, TimeGate eventually opted for “Halo 3 style”, where co-op partners don’t exist in cutscenes. It proved a prophetic vanishing act given the fate of the game’s most crucial cut character – a Weyland Yutani scientist-spy.

This spy would’ve been the fulcrum of the entire story, triggering the USS Sulaco’s SOS, kicking off the story. The aim was to portray him as “complicated, but sort of heroic, trying to help you out by doing the right thing.” The spy was a defector hoping to bring the wrath upon Wey-Yu for the death of a loved one at the hands of the company’s experiments.

I had the opportunity to play a mission where this spy was introduced. It was one of the earliest functional missions, with the spy emphasizing evasion and caution to players as they navigated the remains of Hadley’s Hope. Yet the return of an iconic hero would change everything: Corporal Hicks. “The whole Hicks rewrite was a big shock to much of the team. We’d been working on the project for years and this was not the expectation. To be blunt? Everyone on the team was like, “Wait, what?!’”

Another developer recalls, “The internal reaction to us being told we got Michael Biehn was ‘Cool! But, isn’t Hicks like… visibly dead though? Does this mean another narrative rewrite?’” Sentiments about this were apparently much warmer at Gearbox, purely excited to resurrect the character. TimeGate did not share this perspective, with one developer recalling it as “completely jumping the shark.” Recognizing the many ramifications this would have for a story that had already undergone substantial rewrites. Not only did Hicks’ inclusion mean cutting a central character, but close to half of the game would need to be reworked.

———

With over ten of writing years in the industry, Elijah’s your guy for all things strange, obscure, and spooky in gaming. When not writing articles here or elsewhere, he’s tinkering away at indie games and fiction of his own.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 179.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!