Structures of Power

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #178. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Architecture and games.

———

The periods known in Japan as Taisho, 1912 to 1926, and Showa, 1926 to 1989, were times of significant transformation, marked by rapid modernization, industrialization and pendulum shifts in terms of the cultural and political landscape. These were not only reflected in popular culture but also profoundly influenced the development of Japanese architecture. In these periods, architecture became a tool for expressing national identity, asserting political power and disseminating propaganda during the various imperialist conflicts leading up to and including the Second World War.

This finds a reflection in the contrast between Japanese and Mongolian architecture as represented in Ghost of Tsushima. The game draws a parallel between these two cultures and their respective styles, underscoring themes of identity and conquest, an interesting reversal of the most recent historical precedent.

The Taisho period was characterized by the embrace of western culture and “modernization,” something which is to say westernization. This era saw a shift from the traditional wooden structures of the preceding Edo period to more modern, western, styles of architecture, influenced by fundamentally foreign design principles. The adoption of western architectural style was part of Japan’s broader strategy to present itself as a “modern,” civilized nation on the global stage.

Key architectural developments during this period included the introduction of brick and mortar, then eventually reinforced concrete and steel structures, all of which allowed for the construction of taller and more durable buildings. The use of these materials was symbolic of Japan’s technological advancement and industrial prowess. Notable examples of Taisho architecture include Tokyo Station and the Marunouchi Building which combined traditional Japanese elements with western architectural styles.

When it comes to the Showa period, particularly during the reign of Emperor Hirohito, witnessed the rise of militarism and nationalism in Japan. Architecture during this time became a medium for promoting state ideology and reinforcing the power of the emperor. The state sought to create a unified national identity which emphasized the historical and cultural uniqueness of Japan, typically juxtaposed against western influences.

One of the most significant architectural movements of the Showa period was the Imperial Crown Style which emerged in the 1930s. This style blended traditional Japanese elements along the lines of tiled roofs and wooden structures with modern, once again western, materials and construction techniques. The Imperial Crown Style was used in government buildings, schools and other public institutions, symbolizing the authority and prestige of the Japanese state. While this may sound rather novel and interesting, the idea was most often modern principles of construction with an eastern styled roof.

Notable examples of this style include the National Diet Building in Tokyo and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building. These structures were designed to evoke a sense of grandeur and permanence, reinforcing the power of the state and the emperor. The architecture of this period also included monumental public works including shrines and memorials that served as focal points for nationalistic ceremonies and rituals.

Architecture during the Taisho and Showa periods were filled with symbolism, often used to convey political and ideological messages. The design and construction of buildings were carefully curated to reflect the values and aspirations of the state.

Incorporating traditional Japanese architectural elements, like the use of wooden structures, curved roofs and intricate ornamentation, was a deliberate choice to emphasize Japan’s cultural heritage. These elements were often contrasted with modern materials and construction techniques, symbolizing the country’s ability to blend tradition with modernity. This architectural hybridization was intended to project an image of a nation that was both rooted in its historical past and capable of embracing the future, at least in theory.

The Showa period saw the construction of numerous structures that reinforced the emperor’s divine status and the authority of the state. The Imperial Palace in Tokyo, for instance, was not only the residence of the emperor but also a symbol of Japan’s continuity and stability. The palace’s design, with its blend of traditional and modern elements, was meant to evoke the timeless nature of the imperial institution.

In much the same way, Yasukuni Shrine, dedicated to Japan’s war dead, became a site of nationalistic fervor. The shrine’s architecture, with its imposing torii gates and traditional Shinto design, served as a focal point for state ceremonies and rituals. These ceremonies often emphasized the emperor’s role as a divine leader and the importance of loyalty to the state.

Ghost of Tsushima offers a unique lens through which to explore Japanese architecture and its cultural significance. Set during the Mongol invasion of Japan in 1274, the game presents a rich tapestry of Japanese and Mongolian architectural styles, drawing attention to the contrasts and, less often, the similarities between these two cultures.

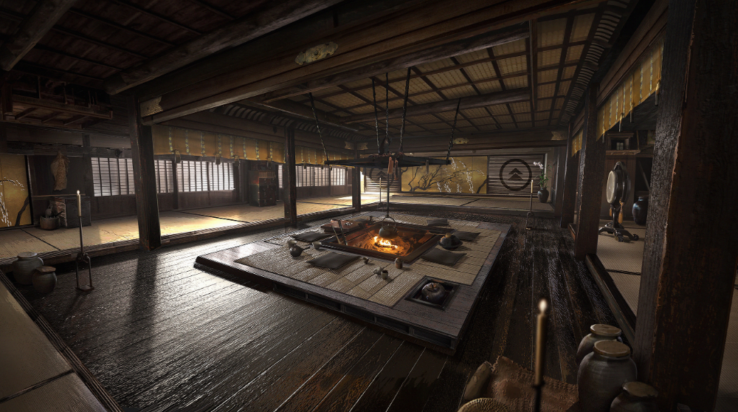

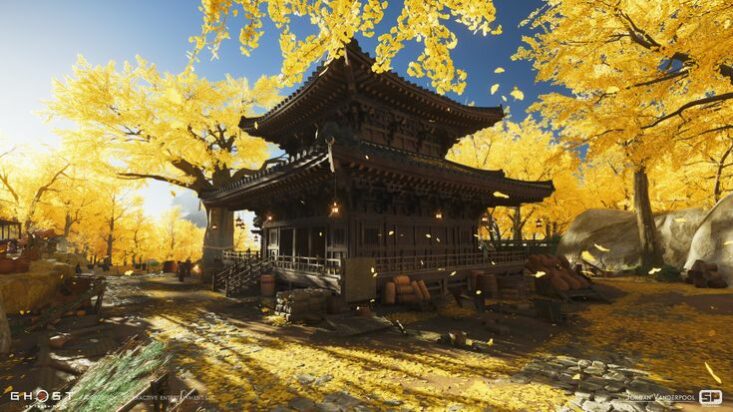

The game’s depiction of Japanese architecture is meticulous, showcasing traditional elements such as wooden structures, tiled roofs and carefully designed interiors. The architecture in Ghost of Tsushima serves not only as a backdrop for the narrative but also as a reflection of the cultural and social values of the time. Temples, shrines and samurai estates are portrayed with great attention to detail.

The design of these buildings emphasizes harmony with nature, a key aspect of traditional Japanese architecture. Gardens, water features and natural materials are integrated into the architecture, reflecting the traditional aesthetic principle of wabi-sabi which values simplicity and imperfection. This connection to nature is contrasted with the more imposing and utilitarian structures of the Mongol invaders, setting up a visual and thematic dichotomy in the game.

In contrast to these Japanese buildings, the Mongolian architecture in Ghost of Tsushima is depicted as more utilitarian and functional. The Mongol camps and fortresses are constructed with a focus on practicality and military efficiency, using materials such as leather, wood and metal. These structures are often temporary and movable, reflecting the nomadic lifestyle of the Mongols.

The game’s portrayal of Mongolian architecture serves to underscore the cultural differences between the two cultures. While Japanese architecture is depicted as harmonious with the natural landscape, Mongolian structures are shown as foreign and imposing, symbolizing the threat of invasion and the clash of cultures. This architectural contrast is further emphasized by the narrative which explores themes of identity, loyalty and resistance.

The juxtaposition of Japanese and Mongolian architecture in Ghost of Tsushima serves as a narrative device, highlighting the differences and occasional similarities between the two cultures. The game uses architecture to tell a story of conflict, resilience and cultural identity.

Architecture in the Taisho and Showa periods of Japan was a powerful tool for expressing national identity, asserting political power and disseminating propaganda. The blend of traditional Japanese elements with modern construction techniques symbolized Japan’s ability to balance tradition and modernity while the construction of monumental public works reinforced the state’s authority and the divine status of the emperor.

Ghost of Tsushima offers a modern interpretation of these themes, using architecture to explore the cultural and ideological differences between Japan and the Mongol Empire. The game’s meticulous portrayal of Japanese and Mongolian structures represents the image of an ideal, highlighting themes of identity, cultural preservation and propaganda. Through its architectural design, Ghost of Tsushima provides insight, although not necessarily answers, regarding the complexities of cultural identity and the impact of foreign influence on heritage.

In both historical reality and virtual representation, architecture remains a potent symbol of cultural values, nationalistic aspirations and collective identity. As we continue to engage with structures and the built environment, we gain a deeper understanding of the cultural and historical forces that shape our world, either for better or for worse.

———

Justin Reeve is an archaeologist specializing in architecture, urbanism and spatial theory, but he can frequently be found writing about videogames, too. You can follow him on Twitter @JustinAndyReeve.