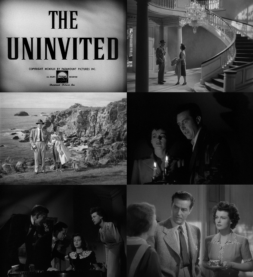

Uninvited and Unseen: Two Chilly Classics of the 1940s on Blu-ray Together

The Uninvited was one of the first movies I ever received for review. This was years ago, when I was still writing the column that would become Monsters from the Vault and Revenge of Monsters from the Vault. Back then, Criterion had just released their very nice Blu-ray of The Uninvited, which I was fortunate enough to cover in that column.

Since then, I’ve been waiting for an opportunity to see Lewis Allen’s follow-up to that film, 1945’s The Unseen, and when Imprint announced a two-disc set containing new releases of both pictures, I knew that my chance had finally come.

Imprint is an Australian boutique Blu-ray company that puts out nice boxed sets that open from the top, utilizing original poster and production art. The only other Imprint set I own is their Silver Screams Cinema box, which trots out six early films from the Paramount vaults including favorites such as The Unknown Terror and Valley of the Zombies. But it was enough to convince me to spring for the new set of The Uninvited and The Unseen.

“It’s getting almost too dark to see you properly.” – The Uninvited (1944)

There are many ways to approach The Uninvited, but most appraisals seemingly begin with the fact that it is one of the earliest Hollywood films to treat seriously the subject of haunting. By the age of the motion picture, ghosts were already somewhat old fashioned, and most movies treated them either as jokes or as put-ons staged by the living, a tradition that would find its most famous iteration in the early episodes of Scooby-Doo.

The Uninvited was among the first of a short-lived string of films in the mid-‘40s which took “grown up” approaches to supernatural storylines, including the classic British anthology film Dead of Night (1945) and The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947). Even then, though, these were the exception, rather than the rule.

Though little enough of it followed, The Uninvited proved that audiences had an appetite for this kind of material, when it was done well. It is reported to have grossed over $500,000 – the equivalent of more than $8 million in today’s money – and outperformed two entries into Universal’s long-running monster franchises released that year, House of Frankenstein and The Invisible Man’s Revenge. (I couldn’t conveniently find box office information on the two films in its Mummy franchise that Universal put out in 1944, but I’m gonna guess that The Uninvited beat them, too.)

Of course, there may also have been other elements at play. It is said that William Hays, architect and unofficial namesake of the infamous Motion Picture Production Code (also known as the Hays Code) received a letter from one member of the National League of Decency which pointed out that, “In certain theaters large audiences of questionable type attend this film at unusual hours. The impression created by their presence was that they had been previously informed of certain erotic and esoteric elements in this film.”

While a 21st-century audience might struggle to find much that was either erotic or esoteric in The Uninvited, it’s also not difficult to read between the lines to see what they’re referring to, as the film’s lesbian undercurrents (in the form of its icy villain, played by author Cornelia Otis Skinner) has been the subject of considerable scholarship in the years since its release, including the 1999 book Uninvited: Classical Hollywood Cinema and Lesbian Representability by Patricia White.

Of course, such things are unlikely to be the sole (or even primary) cause of the film’s popularity at the time of its release or of its longevity in the years since. Ultimately, The Uninvited is simply a cheerfully restrained and above-average chiller, what Carlos Clarens, in his 1967 book An Illustrated History of the Horror Film, calls “an adult, polite ghost tale.”

It doesn’t hurt that an impressive assortment of serious creators were at work both in front of an behind the camera. Adapted from the 1941 novel Uneasy Freehold by Dorothy Macardle, the screenplay was co-written by Dodie Smith, best known as the author of I Capture the Castle and The Hundred and One Dalmations. The film was originally intended for Alfred Hitchcock, though he was ultimately unable to direct and duties fell instead to Lewis Allen.

Charles Lang Jr., the film’s director of photography, was nominated for an Academy Award for The Uninvited (ultimately losing out to Joseph LaShelle for his work on Laura), while the song “Stella by Starlight,” written for the film by Victor Young, became a beloved jazz standard that has since been performed by the likes of Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, and Frank Sinatra, to name a few.

“Cross my heart and hope to die in a cellar full of rats.” – The Unseen (1945)

The success of The Uninvited hangs in the air around Lewis Allen’s 1945 follow-up, nowhere more glaringly than in the ballyhoo on the original poster for The Unseen, which declares it a “Menace more deadly than The Uninvited.”

Which honestly does a disservice to The Unseen, as there’s no way that this pleasant but relatively rote gothic noir feels like anything but an also-ran next to its predecessor. Furthermore, despite shared elements of cast and crew – and the inevitable comparisons that result from that – the two films are actually fairly different. Gone is the airy and charming supernatural menace of The Uninvited and its setting on the Cornish coast, replaced with the gothic gloom of an abandoned townhouse in New England.

That same success had also catapulted Gail Russell into stardom. From her key role in The Uninvited, she is elevated to the status of lead here, as she plays that classic trope of gothic fiction: the pretty young governess who comes into a house full of sinister secrets. Unfortunately, Russell, who had signed a contract with Paramount when she was just eighteen years old, had already taken to drinking to calm her nerves while on the set of The Uninvited, a path that would lead her into chronic alcoholism and her early death at the age of only 36.

Already, the haunted fragility that helped to make Gail Russell so perfect for The Uninvited is beginning to transform into something more brittle and jagged in The Unseen, which works for the material, even while it’s hard not to catch yourself thinking about what it means for Russell’s tragic future.

As for the material itself, gone too are even the subtle spooks of The Uninvited. This is a mash-up of the gothic and the film noir, centered around a 12-year-old crime and the subsequent murders that become necessary to keep it hushed up. It’s a whodunnit with a rather obvious solution and an equally obvious red herring, kept turning mostly by Allen’s able direction and plenty of gothic atmosphere.

For all that the story is familiar, however, that doesn’t mean that it isn’t good. One need look no further than the film’s writing pedigree to see why that is no surprise. The script is an adaptation of a 1942 novel by Ethel Lina White, which is variously known as Midnight House or Her Heart in Her Throat, the latter the working title for the film as well, until it was changed to better capitalize on the success of its elder sibling.

White wrote a number of similar spooky mystery and crime novels throughout the 1930s and into the early ‘40s. The best known of these include the novels from which Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes and the 1946 film The Spiral Staircase were adapted, though I’m also personally partial to Wax, which was re-released a few years ago by Valancourt Books. For those who haven’t seen it, The Spiral Staircase (which has been remade several times) is one of the best films of this type made in this era, and is well worth tracking down if you like this sort of thing.

When it came to adapting the novel to the screen, those duties fell to Hagar Wilde (a less-familiar name, but she was a co-writer on Howard Hawks’ Bringing Up Baby, among others) and Raymond Chandler, who obviously knows his way around a noir script.

Director Lewis Allen later recalled creative differences between Chandler and producer John Houseman. “Chandler was writing the script and John Houseman was always interfering, wanting to change this and change that,” Allen told Tom Weaver for the book Science Fiction and Fantasy Film Flashbacks. “I was on Ray Chandler’s side; I said to Houseman, ‘Look, John, Ray’s a very good writer. Let’s trust him.’”

According to Allen, Chandler’s reaction to Houseman’s changes was less equanimous. “Ray got up and took the script and threw it in the waste basket,” Allen recalled, “he said, ‘Look, I’m the fucking writer on this picture, not you!’”

———

Orrin Grey is a writer, editor, game designer, and amateur film scholar who loves to write about monsters, movies, and monster movies. He’s the author of several spooky books, including How to See Ghosts & Other Figments. You can find him online at orringrey.com.