The World Outside the Glass was Almost Gorgeous

This is a feature excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly #177. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

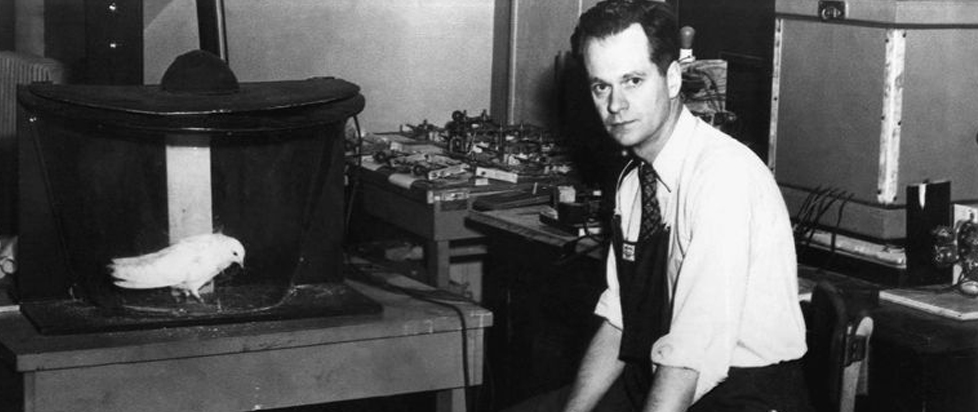

In the 1930s, a man named B.F. Skinner made a box.

__

I started playing videogames with my best friend. His name’s Rory. We’ve known each other for as long as I can remember. We came up in arcades, figuring out the best way to spend our limited cash. You had to balance how much you liked a game with how much it cost. Star Wars Trilogy Arcade? Sublime. A banger. But it costs more than a single run on Tekken Tag, and eventually, it ends. And as long as you could keep winning in a fighting game, and there were people willing to spend their quarters, you could keep playing. We got good, early on, at cost-benefit analysis. Bang for your buck was the name of the game.

__

Skinner was a graduate student at Harvard University in the 1930s. Primarily interested in behavior and psychology, Skinner thought free will was an illusion. Instead, he believed human responses were based on the consequences of their previous actions. If the consequences were bad, there was a good chance you wouldn’t do that thing again. You don’t put your hand on a hot stove twice. But if the response was positive – a reward, for instance – you’re more likely to do it.

At the time, we already knew that you could condition responses to certain stimuli. Think of Pavlov’s dog: by ringing a bell when he gave a dog food, Pavlov eventually conditioned the dog to start salivating at the ringing of the bell because it associated that sound with food. This is called classical conditioning.

Skinner believed you could go a step further. What if you could condition not only a response, but the ways animals made choices? What they would choose, how often they did it and why.

Skinner called this process operant conditioning.

__

Eventually, Rory and I, and the rest of our friends, convinced our videogame-averse parents to buy home consoles, Game Boys, Game Gears, if you were nasty. What started in the arcades continued on small screens, and the kinds of games we played changed, too. Fighting games stayed the same, but everything else changed. Our light gun games became first-person shooters. GoldenEye, Doom, Quake, Halo. Arcade classics like Crazy Taxi came home. We got really into RPGs; talk to me any time about Xenogears, or Final Fantasy, or Knights of the Old Republic, and you’ll have to pay me to shut up. Rory developed a fondness for Metal Gear Solid. We get really into Pokemon. For a while, games became something we paid for once and played a lot. They came with cheat codes, easter eggs, unlockable difficulties and costumes, and so on. It’s easy to romanticize your childhood and talk about how things were better “back in the day.” Studies have shown that people love to do that, especially with art. The golden age never was the current age. But I have to remind myself that this era existed. Even though I lived it, it doesn’t feel real.

I don’t remember what the first game I bought DLC (downloadable content) for was, but I think it was probably Halo 2. Map packs. Pay more, get more game. It seemed like a pretty good deal. And the maps were good. I didn’t mind.

And the idea of paying to play wasn’t crazy. We grew up on MMOs: Ultima Online, Star Wars Galaxies, City of Heroes, Final Fantasy XI, The Matrix Online, any game of the pre- and post-World of Warcraft era, and WoW itself. You paid to play, but you got a lot of stuff for your money. Every part of the game was open to you, and new stuff was constantly being added. Supporting that seemed reasonable, and when I was tired, I could cancel my subscription for a few months. Barring a shutdown, which was generally communicated months in advance, those worlds would be there when I wanted to come back. And there was so much to do. You could play however you wanted.

Somewhere along the line, games got more and more online, and we followed. Halo 3 and World of Warcraft defined my last year of high school and most of my college years, at least in terms of games. No matter where my friends had gone, we could all play together. It kept those friendships together. Then ODST. Then Reach. Gears of War. BlazBlue. Mortal Kombat 9. League of Legends, much to my eternal regret, but it was free unless you wanted to buy a character or a skin. Halo Wars, where our 3v3 team was one of the best in the world. StarCraft II. And there were still those single-player experiences. When Dragon Age: Origins came out, everyone I knew bought it. Dead Space. Red Dead Redemption. Mass Effect. We told stories over cheap Mexican food, beer we weren’t legally allowed to have and in party chat. You paid for a game, and then you played it. If you wanted more game, you paid for more game. I don’t know anyone that didn’t buy Lair of the Shadow Broker. Who didn’t want to spend more time in that world, with those characters? $10 was a reasonable price to pay.

You might be wondering why I’m telling you this. Where is this story going? What does this have to do with B.F. Skinner? In the words of Charles Dickens, “Marley was dead to begin with.” You must understand – for some of us, be reminded – what was, to understand where we are. I can tell you no story but my own. There is a point here, and if I do my job correctly, by the end you may spot how the trick works. Are you watching closely?

In 2007, I remember thinking Halo 3 was the future. Imagine it: all the tools to create all the custom games you wanted. The ability to watch and edit any replay of any match you’d played. A photo mode. A replayable campaign packed with funny skulls and arcade scoring. And Forge, of course. The ability to edit any map you wanted, to create all sorts of insane things. You could buy Halo 3 once, and play it forever. You were only limited by your imagination and that of the Halo community. Like WarCraft III or StarCraft before it, you could create something beautiful, if you took the time, at no extra cost, unless you wanted more maps. Bungie and Blizzard had done the impossible. They had given their games to their players, turned them loose with their blessing. The good stuff was even spotlighted so people could find it. This was the future. It had to be.

__

Like any good scientist, Skinner set out to prove his theory. He started with what he called an operant conditioning chamber. The device was simple. It contained a lever or a button. Sometimes, there were also lights or an electrified floor to discourage behaviors he didn’t want. Skinner would place an animal – he started with rats, and later moved on to pigeons – in the box. If the rat pulled the lever or the pigeon pecked the button, the box would give them food.

By tracking how often the animals pulled the lever or pecked the button, Skinner proved that he could condition them to make a choice. Skinner also discovered he could condition the animals to avoid certain behaviors, or only perform them at a specific time.

Let’s say, for instance, that the box contained lights. Skinner discovered that if he made the light green, and the animal pulled the lever or pressed the button to get food and got it, the animal would perform that action when the light was green. If he shocked the animal through the electric floor when the light was red, however, Skinner learned that he could discourage the animal from performing that action.

__

You can trace the rise of cosmetic DLC to the Horse Armor DLC Pack in The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, which was released on April 3rd, 2006. At the time, nobody I knew could figure out why someone would want the horse armor. It didn’t do anything besides make your horse look cooler. Why would you spend money on that? But people bought it. A lot of people bought it. Years later, I would learn many of the people who openly mocked the idea (and legacy) of horse armor, and the people who bought it, had actually purchased it themselves. They just hadn’t owned up to it publicly.

Anyone watching the bottom line began to realize that DLC was a great way to make money. People wanted to play for more content, but map packs in online games segmented the community. If you wanted to play them, you’d have to go into specific playlists, or you could only play against people who also had those maps. So that was out. But League of Legends had shown that people weren’t against spending smaller amounts of money on games they were already playing a lot, especially if that game was free. Why spend $10 on a single-player DLC you might only play once or twice when you could spend $7 on an Ahri skin you could use forever?

They weren’t the same things, though, so they invented a new word: microtransactions. It’s amazing how much better you can make something sound by talking about how small it is.

__

I wish I could tell you I never spent money on League of Legends. I wish I could tell you I’d never spent money on an Ahri skin, or an Ashe skin, or anything else in any other game that was designed to deny you something to make money. But that would be a lie. It’s hard to look yourself in the eye and realize you’re part of the problem. But the first step to solving a problem is admitting a problem exists, and the role you played in causing it. None of us are innocent.

__

Skinner made several other important discoveries regarding operant conditioning. First, he discovered that it works on humans. Second, he discovered that primary conditioners – rewards that are biological needs like food, water, sleep, shelter, sex, etc. – have diminishing returns once that need is fulfilled. You don’t eat when you’re not hungry. But there are also what Skinner called secondary reinforcers that are learned and don’t occur naturally. If your dog does a trick and you give him a treat while saying “good boy,” your dog will eventually associate the words “good boy” with the treat, and thus, a reward. Over time, “good boy” becomes a secondary reinforcer.

For humans, secondary reinforcers come in the form of money, praise and token economies – tokens, chips, stars or other forms of currency that are used as rewards for desired behaviors and can be used to acquire primary conditioners or other desired objects. The benefit of secondary reinforcers is that you can never have enough of them. You can never be satisfied. If someone offers you $10,000, you’re not going to say no. If you’ve been paying attention, you can probably see where this is going, and what the magic trick is.

Skinner made one more discovery, and it’s probably the most important of all: rewarding someone every time they perform an action isn’t the best way to get them to repeat that action. Instead, it’s better to reward them randomly, or on a regular schedule. This is the psychology behind gambling and rewards points, respectively. And with that, the last piece of the puzzle falls into place. Do you see it? The magic trick is that there is no magic trick.

———

Will Borger is a Pushcart Prize-nominated fiction writer and essayist who has been covering games since 2013. His fiction and essays have appeared in Your- Tango, Veteran Life, Marathon Literary Review, Purple Wall Stories, and Abergavenny Small Press. His games writing has also appeared at IGN, TechRadar, Shacknews, Into the Spine, Lifebar, PCGamesN, The Loadout, and elsewhere. He lives in New York with his wife and dreams of owning a dog. You can find him on X.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 177.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!