Taming the Beast

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #176. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #176. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Architecture and games.

———

In the grand tapestry of economic history, few events resonate as dramatically as Japan’s Bubble Economy of the 1970s and 1980s, along with its subsequent burst in the 1990s. This particular period, marked by rapid economic growth and speculative asset inflation, had profound implications for Japanese society, culture and of course politics.

Encapsulating the scale of this financial upheaval, the legendary monster and icon of destruction, Godzilla, has always stood as a symbol of the catastrophic aftermath, particularly when it comes to ordinary people. Standing at the heart of this narrative lies another force of destruction, the enigmatic figure known as the Dark Lady of Osaka, whose story is a poignant reflection of the period’s excesses and the human cost of financial folly. In retrospect, we can observe the architecture of collapse, and the makings of a monster.

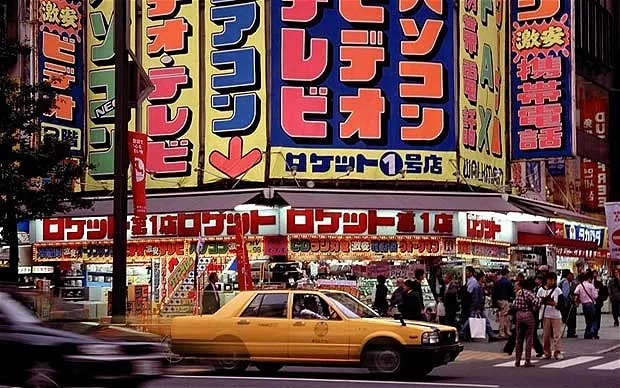

The origins of the Bubble Economy can be traced back to the period following World War II, a time of reconstruction and rapid industrialization, following the devastation produced by American and British bombing. By the 1980s, Japan had emerged as a global economic powerhouse. The gross domestic product of the country soared, with technological innovations in the consumer electronics and automotive manufacturing sectors attracting attention around the world, causing many of its corporations to become dominant players in various international markets, resulting in all sorts of social anxiety, as domestic industries faltered. This period of prosperity was fueled by an accommodating monetary policy, financial deregulation and a widespread cultural emphasis on collective success.

Real estate and stock prices skyrocketed, with speculative investments becoming the norm. Land values in the central parts of Tokyo in particular attained astronomical heights, making the city more valuable than the entire state of California, according to some estimates. Prices on the Nikkei 225, a key stock market index, more than tripled between 1985 and 1989. For many people in Japan at the time, the good times were certainly rolling, with no end in sight.

Beneath the surface on the other hand, the seeds of destruction were being sown. The speculative fervor led to unsustainable valuations of both real and imagined property, allowing the financial system to become increasingly fragile. The economy was teetering on the brink of collapse, cowering in the shadow of Godzilla.

The economic bubble burst in 1991, unleashing a form of cascading chaos that was very much akin to Godzilla’s rampage. The stock market plummeted, and property values collapsed, the Nikkei 225 losing half its value by the beginning of 1992, real estate prices in Tokyo falling by up to 80 percent. The once mighty investment banks and other financial institutions found themselves drowning in bad loans and speculative debt, leading to an economic crisis that would take years to resolve.

The effects are in fact still rippling through Japanese society, as the human toll was profound. Unemployment rose for the first time in decades, wages began to stagnate and the system of lifelong employment, a cornerstone of Japanese corporate culture at the time, was almost entirely shattered. The social fabric began to fray as the economic downturn eroded trust and confidence in sometimes longstanding institutions, both private and public.

The film Godzilla was released back in 1954, decades before the burst of the Bubble Economy. The character would go on to represent collapse, embodying the existential dread and the uncontrollable forces that challenged human ingenuity and resilience, a force overwhelming the careful planning and hard work of millions, leaving a trail of devastation.

In the economic turmoil of the 1990s, the story of the Dark Lady of Osaka emerged as a symbol of the period’s excesses and the human toll of the collapse, in much the same way as Godzilla. This enigmatic figure, Nui Onoue, was a prominent person in the bustling nightlife of Osaka during the 1980s, epitomizing the glitz and glamor of the period, their lavish lifestyle being funded by speculative investments and connections to powerful politicians, bankers and businessmen.

Their rise mirrored the surge of the economy. They became a fixture at high end clubs, within fashion circles and in real estate ventures, embodying the opulence that characterized the bubble years. As the bubble burst, however, their fortunes plummeted, rapidly. Investments that once seemed infallible turned into financial traps, and their network of affluent acquaintances began to crumble under the weight of bad debts, fast friends and sketchy accountants.

The fall of the Dark Lady from grace was swift and unforgiving. They were once known for their trustworthy investment advice, ostensibly drawn from divination, but in reality, a product of insider trading, basically tips and slips from patrons. They were a prominent hotel and restaurant owner, gaining a reputation for predicting stock market trends, taking out substantial loans and investments, while encouraging others to do the same. At the peak of the economic ecstasy, their net worth reached an estimated $4.4 billion, but their luck promptly reversed when the bubble burst, revealing fraudulent activities including fake certificates of deposit. They were eventually arrested in 1991, being sentenced to more than 10 years in prison.

The human cost of the bubble’s burst extended far beyond the elite circles of the Dark Lady. Countless ordinary people who had invested their life savings into the soaring stock and real estate markets found themselves facing financial ruin, similar to the Roaring Twenties and the following Great Depression. The promise of rapid riches led many to assume significant debt in the aim of gaining financial securities, often using their own home as collateral. When the market collapsed, these people were left with largely devalued assets and overwhelming liabilities.

The prospect of unemployment, once a rare phenomenon in the job-for-life culture of the time, surged in the 1990s. Recent graduates from even the most elite institutions like the renowned University of Tokyo struggled to find work and many middle managers or professionals were forced into early retirement, facing lengthy unemployment only bounded by social security. The psychological toll was immense, leading to a rise in mental health issues and social isolation, both of which are still experienced even today.

The film Godzilla portrays countless scenes of ordinary citizens fleeing in terror, their lives upended by the mostly pointless rampage of the monster. In much the same way, the economic collapse of the Bubble Economy left countless families scrambling to rebuild their lives in the wake of the wreckage of their newly experienced financial insecurity. The fear and uncertainty of this period were palpable, mirroring the anxiety and helplessness depicted in the monster’s wake.

In the aftermath of the bubble’s burst, the Japanese government faced the monumental task of stabilizing the economy and restoring public confidence, a tall order to say the least. Policies aimed at restructuring the financial sector, addressing bad loans and stimulating economic growth were implemented. These were largely unsuccessful at first, but eventually, the Bank of Japan lowered interest rates to basically nothing, introducing quantitative easing measures to inject liquidity into the economy, in addition to broad spectrum subsidies.

These efforts on the other hand fell short of expectations. The result was the Lost Decade, a term used to describe those affected by the prolonged period of economic stagnation throughout the 1990s, largely synonymous with the struggle to recover from the burst. Despite various stimulus packages and reforms, the economy remained sluggish and deflationary pressures persisted, akin to the stagflation of the 1970s in America.

The governmental attempts to control the economic aftermath of the Bubble Economy can be likened to the recurring efforts to contain Godzilla. Despite numerous strategies and interventions, the underlying issues proved resilient and challenging to overcome. Similar to how Godzilla reemerges despite the best efforts to contain this horrifying monster, the consequences of the Bubble Economy continued to haunt the society and economy of Japan for decades to come.

The impact of the Bubble Economy and its eventual collapse left an indelible mark on Japanese culture, influencing everything from art and media to the structure of public institutions, privatization for example rendering life in the remote parts of the country largely impossible, especially for the elderly, as the Graying of Japan continued to progress. Japan Post was a lifeline for tens of thousands, workers providing essential services including news and banking. The excesses and eventual downfall of the period became recurring themes in films, novels, anime and manga, with creators using their works to explore the social impact and personal stories of those affected by the economic turmoil.

When it comes to cinema, the already longstanding Godzilla franchise experienced a resurgence in the 1990s, with new releases reflecting contemporary anxieties, mostly economic as opposed to nuclear, as before. The monster, originally conceived as a metaphor for explosive destruction, came to symbolize more abstract fears including economic instability and societal degradation. The parallels between Godzilla’s chaos and the economic collapse of the time provided a rich narrative framework for exploring these themes.

Literature from this particular period also depicted the disillusionment and struggles of the Lost Decade. Authors along the lines of Haruki Murakami delved into the psychological and social ramifications of the economic collapse, using the lived experience of their characters to critique the excesses of the 1980s and the challenges of the 1990s, at this point clearly stretching into the 2000s, if not later.

The tale of the Bubble Economy and the metaphorical devastation wrought by Godzilla provides valuable lessons for the future of generations everywhere, a key takeaway being the importance of sustainable economic practice and the danger of speculative investment. The rapid rise and fall of the economy in Japan between the 1970s and 1990s reveals the risk of unchecked greed and the need for robust regulatory frameworks, if not real structural change and the dismantlement of capitalistic frameworks. The human struggles moreover highlight the social and psychological cost of such economic volatility, policymakers and business leaders failing to even today consider the broader impact of their decisions on ordinary people, not to mention the creation of economic environments that protect against such dramatic downturns, all in the name of immediate profits.

As the country continues to navigate its economic future, the legacy of the Bubble Economy continues to serve as a cautionary tale in Japan. While the nation has made significant strides in recovering from the Lost Decades, the scars of the economic past remain a poignant reminder of the destructive potential of greed, corruption, incompetence and mismanagement.

When it comes to Godzilla, embodying destruction and uncontrollable force, the figure remains a powerful lens through which to view the Bubble Economy, and the Great Recession which it in many ways mirrors. The rise and fall of this economic giant left a lasting impact on Japanese society, culture and even the global economic landscape. Reflecting on this period and remembering that true monsters are often a byproduct of our own collective action is critical. By learning from the past and embracing new concepts of political economy, we can prevent the past from repeating itself, ensuring a more stable and prosperous future for people everywhere.

———

Justin Reeve is an archaeologist specializing in architecture, urbanism and spatial theory, but he can frequently be found writing about videogames, too. You can follow him on Twitter @JustinAndyReeve.