Purrcy from Mystic Mansion

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #176. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Fictional companions and goth concerns.

———

During the indie sleaze era, I wrote my senior thesis on Japanese kawaii culture as a form of rebellion. Under the guidance of my advisor, Kumiko Sato, I passed with honors.

Years later, I struggle to remember much of what I learned, but I still engage with cuteness as a consumer. I used to consume cuteness in accessories and clothes; now, I prefer to consume cuteness in the form of games.

First, here is something I found in my thesis which proves, empirically, that I used to be smarter: “Kawaii” only emerged as a commonly used word in the past century. Tomiyoshi Maeda’s Japanese etymological dictionary, Nihon Gogen Daijiten, explains the history of kawayushi, an etymological predecessor of kawaii. The first meaning of kawayushi is cited as “embarrassed,” in use around 1120 CE. A later definition is “pitiful,” in use circa 1216 CE. The final definition is “resembling love,” in use circa 1563 CE. The etymology of kawayui and kawayushi is also related to mabuyushi, meaning “beautiful” or “dazzling,” as well as omowayushi, meaning “bashful” or “self-conscious.” The suffix “yushi” is assumed to have the same etymology in all three words. Per Maeda (my translation), the change in word form from “kawayui” to “kawaii” involved adopting Chinese characters (kanji) and eventually became a part of the everyday Japanese lexicon. It is interesting to note how “embarrassed” and “beautiful” might meld together to create “cute,” a word with connotations of physical attractiveness as well as vulnerability. Indeed, cuteness is almost a perfect bridge between the concepts of bashfulness and beauty. Something cute is aesthetically pleasing, but distinct from the mature, confident connotations of something “beautiful.”

This is relevant not only because I want to show off that I once translated an etymological dictionary entry (whereas this morning I spilled an entire carton of oatmeal because I lifted it from the lid), but also because thinking of “cuteness” as “pitiful” feels relevant. In games with kawaii aesthetics, we often want to help the characters because they seem . . . well, a little pathetic.

Visual signifiers of kawaii include a round face, low, forward-facing eyes, youth, vulnerability and harmlessness (yes, that’s also from my thesis).

Think about the animals of Animal Crossing, Animal Restaurant, Neko Atsume, Neopets, Tamagotchi or near-infinite others. Whether or not you’d describe them as “pitiful,” they do need help. You have to feed and play with your Neopets, or they cry and get sick. You have to feed your Tamagotchi or, in the great generational trauma of millennials, it dies. As Yussef Cole writes of Animal Crossing: “It isn’t [. . .] a huge leap for us to care about the helpless and sweet denizens of our virtual island town, designed as they are to tap into that very urge.” They’re all designed with visual signifiers of cuteness and pitifulness so that we continue to care for them. This must be why I have never deleted my Neopets account.

Perceived helplessness can, of course, be manipulated not only by marketers trying to sell games, hair accessories or Trapper Keepers, but also by the cute characters themselves. In a mobile game I’m currently playing, the characters show visual signs of cuteness, and they do need your help, but the central animal “friend” is not exactly pitiful.

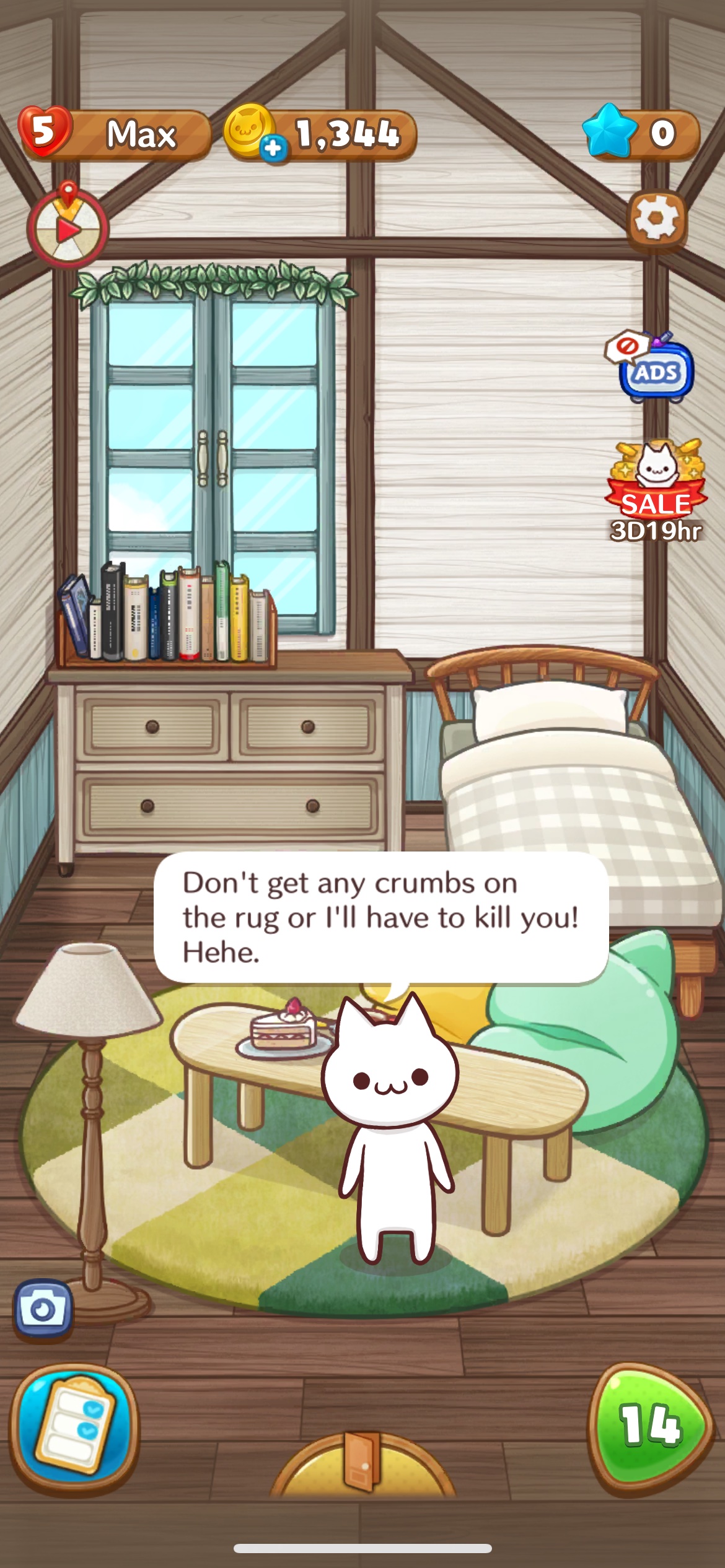

This is Fundoshi Parade’s 2020 match-three game Mystic Mansion, in which a cat named Purrcy requests assistance in fixing up a building, thereby helping the animals who live inside. This sounds like standard “helping cute animals” gameplay; the major difference is that Purrcy is lowkey terrifying. He constantly drops threats like, “Don’t get any crumbs on the rug or I’ll have to kill you!” Or, “The punishment for not sorting your trash is seriously brutal.” With his face sinister and shadowed: “It’d be bad if a human got into our world” (he has not yet discovered my secret).

I find myself thinking about how Purrcy fits into the kawaii template of vulnerability and harmlessness. Purrcy does have these visual signifiers. I do want to help him. I am also terrified of him.

This falls under the same umbrella as dolls and small children being so frightening in horror movies. They’re scary because they look pitiful and then they murder you. Purrcy’s round face and low, forward-facing eyes make me want to help him, no matter what thinly veiled threats he drops. There’s nothing for me to do but keep cleaning up his building, helping him, pitying him, wondering how he’ll turn on me. I have not yet determined whether Purrcy will murder me when he finds out I am human. I don’t think it’s that kind of game. I could be wrong.

———

Deirdre Coyle is a goth living in the woods. Find her at deirdrecoyle.com or on Twitter @deirdrekoala.