This is Your Badness Level: Lilo & Stitch and Mental Health

This is a reprint of a feature story from Unwinnable Monthly #173. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

For those who don’t use Letterboxd, on your profile page on the movie-focused social media site, you have a space to put your “top four” favorite movies. As is the case for most people, my top four is not exactly static, but there are two movies that pretty much always have a place there: House on Haunted Hill (1959) and Lilo & Stitch (2002).

The latter is often surprising for people who know me primarily as a horror writer and the “monster guy.” I once had someone ask me if its presence on my top four was because I was a “big Elvis fan.” I told him, honestly, that it was because I’m a big Lilo & Stitch fan.

And I’m obviously not alone. While Lilo & Stitch did well for itself in theaters – it was a Disney animated feature, after all – it has found its real footing in merchandizing, and you can get Stitch’s (undeniably adorable) face plastered all over pretty much anything these days.

In proper Disney fashion, the movie also gave rise to a variety of spin-offs and sequels, including a Saturday morning cartoon-style animated series which ran from 2003 through 2006 on ABC and the Disney Channel. Familiarity with these is mostly not necessary for us today, but the 2005 direct-to-video sequel Stitch Has a Glitch is going to be vital to the topic we’re here to discuss.

There are a lot of reasons why I like Lilo & Stitch so much. I like the writing and artwork of creator Chris Sanders. I like the painted backdrops and Hawaiian locale. And, of course, Stitch is a monster, and I am the monster guy, after all. The movies pay homage to the big bug flicks of the ’50s, to alien invasion pictures and so on. But it also goes deeper than that. As a weird kid myself, who grew up into a weird adult, it’s easy to see aspects of myself in both Lilo and Stitch – and I’m not alone.

Plenty of people identify heavily with one or both characters, and one doesn’t have to look far to see Lilo & Stitch held up as an example of autism representation, for instance. And it is representation, albeit of a slightly different kind, that I’m here to discuss.

There are obvious mental health parallels at work in Lilo & Stitch. Lilo is attempting to process the grief of her deceased parents. She grapples with anger management and, according to at least some armchair clinicians out there, PTSD. She struggles to express herself in a way that connects with other people, and she becomes frustrated when she can’t.

Lilo & Stitch also showcases how such mental health struggles can be exacerbated by external conditions. Certainly, Lilo’s life is made harder by the absence of her parents, but it goes beyond grief. The financial situation in which she and her older sister Nani find themselves also makes everything harder – and further isolates Lilo from her peers.

For me, one of the most heartbreaking scenes in cinema is the moment when Lilo tries to play with the other kids by showing them her doll, Scrump, which she made herself. The other kids reject the doll and, with it, Lilo as well. Frustrated, Lilo throws Scrump to the ground and storms away, only to come running back, scoop up the doll, and hug it tightly – a moment that I can feel down to my marrow.

As I said, I can certainly see aspects of myself in Lilo, but the real glimmers of recognition, where mental health is concerned, come from Stitch. There’s no need to get into specific diagnoses but, like a lot of people, I experience a particular cocktail of anxieties, quirks, trauma responses and other things that fall under the broad umbrella of “mental health.” And like anyone, my specific combination of these things is unique to me. No two people are alike, even (maybe especially) in their struggles, which is sometimes easy to forget in this age when all experiences are seemingly boiled down to TikTok trends and internet memes.

I have rarely seen my own particular mental health journey echoed onscreen in a way that resonated quite like the one Stitch experiences in Stitch Has a Glitch. In the first movie, Stitch comes to Earth without a purpose, and finds one in Lilo’s family. Initially, like Lilo, he struggles to interact with his surroundings in healthy ways. In his case, this is because of his “destructive programming” from his creator, Jumba Jookiba. But it is also because he has nothing else. Because he is lost and alone.

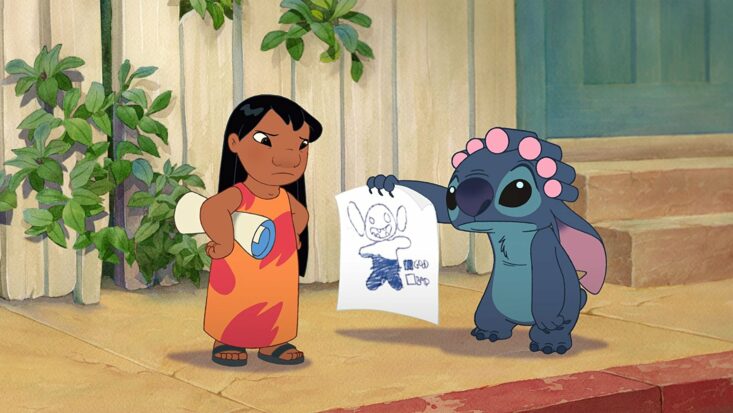

This same “destructive programming” can be seen as a metaphor for mental illness. What is mental illness, after all, but a kind of harmful programming in our own brains. Many of us struggle with “negative self-talk;” inner voices that diminish or harm us, driving us, in turn, too often harm those around us, though not on purpose. In Lilo & Stitch, Lilo represents this via a childish simplification – Stitch’s “badness level,” which, as she points out, is “unusually high, for someone your size.”

By the end of Lilo & Stitch, however, Stitch has largely overcome his programming and found his place as part of Lilo’s family. In fact, the ending montage shows Stitch as more than merely a part of the group. It shows him specifically as a homemaker, packing lunches, baking cakes, doing laundry, and so on.

For most of a decade, I’ve been working full-time as a freelance writer, meaning that I work from home and have an extremely flexible schedule, while my spouse holds down a more “normal” 9-to-5 type job. Partly because I am home more, I have become more of a homemaker myself in these last few years, and I’ve found that I enjoy it. To put it in the rather cliched terminology of “love languages,” one of the ways that I show my love is definitely through “acts of service.”

Part of this can also be traced back to my own background, specific traumas and particular anxieties. I struggle to feel like I am of value to the people around me – but I also take genuine pleasure from making myself useful and making others happy, something I didn’t fully understand when I first saw Lilo & Stitch many years ago, but which has provided a sense of homecoming upon repeated re-watches.

Though the ending of Lilo & Stitch paints a rosy picture, however, the journey toward mental health is not one that occurs without setbacks, and that’s where Stitch Has a Glitch comes in. The premise of the sequel is that Stitch’s creation was interrupted and, as a result, he has a “glitch” that causes him to act out despite his best intentions.

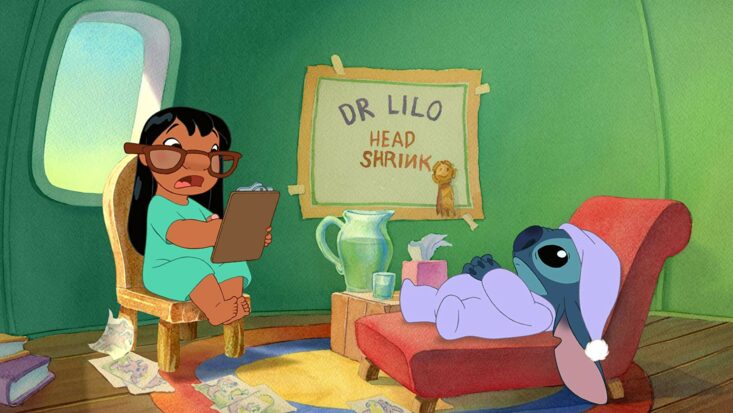

Even before this glitch becomes apparent, however Stitch is haunted by his own “destructive programming,” just as many of us are haunted by that “negative self-talk” which tells us that we will never be good enough, that we will always hurt those we love simply by existing. In his nightmares, Stitch wreaks havoc on the island, which prompts Lilo to put him through a childish version of “talk therapy” before determining that his goodness level is higher than ever.

Shortly thereafter, however, Stitch begins to “glitch.” When he glitches, he does exactly what he fears that he will do – damaging and destroying the things around him but, much worse, damaging the trust and hurting the feelings of those he loves. And when he “glitches,” his family are understandably frustrated.

“He ruined everything,” Lilo says, after one of his episodes.

“It’s not my fault,” Stitch replies.

“Then whose fault is it?” she demands.

It’s a conversation that many of us have had, if only with ourselves. We’re afraid that our flaws and our struggles make us unlovable and, worse, unworthy of love. That we will hurt those who make the mistake of loving us because we can’t be anything other than the way we are.

“I know what’s wrong with you,” a wounded and betrayed Lilo lashes out, when Stitch tries to explain that something isn’t right. “You’re bad. And you’ll always be bad.”

Ultimately, that’s what I fear. It’s what my negative self-talk whispers in my ear in the dark watches of the night. I’m afraid that I’m not actually mentally ill; that I’m not a victim of trauma and some faulty wiring, doing the best I can with the tools I have; that I’m not just a basically ordinary person with a not-particularly-noteworthy collection of quirks and flaws. That I am, instead, simply and irrefutably bad, and that no matter what I do, how hard I try, or how much I want to be good, I will always be bad.

By the end of the film’s brief 68-minute running time, Stitch’s “glitch” is treated via a widget whipped up by Jumba, and the power of love and friendship and all that jazz. And many of us find ways to treat our own glitches via talk therapy, medication and coping strategies that help us to care for ourselves and those around us. It’s never a perfect or an easy fix – nothing in real life ever is – but sometimes watching a cute little blue alien struggle with the same things we struggle with can make it a little easier, at least for a while.

———

Orrin Grey is a writer, editor, game designer, and amateur film scholar who loves to write about monsters, movies, and monster movies. He’s the author of several spooky books, including How to See Ghosts & Other Figments. You can find him online at orringrey.com.