Rough Shadows: The Whistler Films on Blu-ray

“I may not be the greatest detective in the world, but I am the most unusual.”

These days, we mostly know William Castle for his string of gimmicky horror films, beginning with Macabre in 1958. Before that, however, he already had a prolific career as a director of genre programmers, including four of the eight films in the Whistler series from Columbia.

Like Universal’s Inner Sanctum Mysteries before it, the Whistler began life as a radio drama in 1942. Each episode was introduced and narrated by an omniscient and sardonic figure known simply as the Whistler, who functioned not only as host for the audience but also as a sort of Greek chorus, occasionally adding commentary to the action and even taunting the characters, though they could rarely hear him.

The films take a similar bent. Focusing on tales of mystery and crime, each one is narrated by the Whistler – voice provided by an uncredited Otto Forrest – and the first seven of the eight movies star Richard Dix (The Ghost Ship), playing a different character in each picture, similar to what Lon Chaney Jr. was doing in the Inner Sanctum films at the same time.

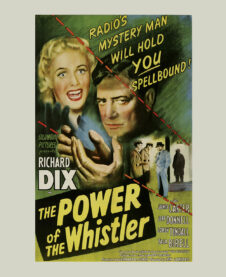

Simply titled The Whistler (1944), the first film in the series (which is also the first one directed by Castle) sees Dix taking on the role of a man who tries to commit suicide by hiring a contract killer to knock him off, only to find that he can’t call off the contract when he changes his mind. It’s a plot that has been used elsewhere, but it’s a good one, and it’s put to good use here thanks to the always-reliable J. Carrol Naish (House of Frankenstein) as the hitman.

This was Castle’s second or third feature as director, and he purportedly liked the script and the experience, writing in his 1976 memoir Step Right Up! that, “I tried every effect I could dream of to create a mood of terror: low key lighting, wide angle lenses to give an eerie feeling and a handheld camera in many of the important scenes to give a sense of reality to the horror.”

Sadly, this was still a full decade before Castle’s real horror days, so even once Naish’s hitman settles on the idea of scaring his quarry to death, Castle doesn’t yet trot out any of the gimmicks or low-rent horror aesthetics that he would later become synonymous with.

In proper programmer fashion, The Mark of the Whistler was released just a few months after the first film, and all eight would hit screens within four years. Castle was back in the director’s chair for Mark of the Whistler, in which Dix plays a drifter who attempts to claim the money in a dormant bank account only to get caught up in predictable drama. This time around, the screenplay is adapted from a 1942 short story by Cornell Woolrich (“Dormant Account”).

Despite several mainstays of gothic plotting (mistaken identities and familial revenge) and nice turns from a couple of heavies – including Matt Willis, who played the wolfman in Return of the Vampire – there are even fewer opportunities for horror hijinks in Mark of the Whistler. Which is not to say that Castle doesn’t still get to have a little fun and show off his chops when it comes to paranoia and timing. Aficionados of these kinds of movies will also recognize Willie Best in an uncredited role as a men’s room attendant.

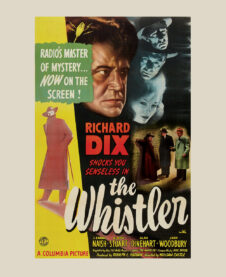

As it happens, a different alum of Return of the Vampire is present for The Power of the Whistler from 1945, the first movie in the series not to be directed by William Castle. Instead, Lew Landers, who previously helmed Return of the Vampire, The Boogie Man Will Get You, and the 1935 version of The Raven is in the director’s chair this time around, so it’s not like our horror credentials are reduced in any way.

It also doesn’t hurt that the setup is more horror than ever before. This time around, Dix plays a guy who gets in an accident and loses his memory, while a girl at a bar predicts his fortune and says that he’ll die within 24 hours. Naturally, the two team up to try to figure out who he is and why he might be doomed, and in so doing uncover more than they bargained for. Janis Carter, who played the charming reporter in Mark of the Whistler, is back as the leading lady in this one, too.

The script this time around comes from one Aubrey Wisberg, whose other screenwriting credits include (but are fortunately not limited to) The Man from Planet X and, uh… Hercules in New York. Let’s try not to hold that against him.

Dix is probably better as the conflicted (and ultimately sinister) character here than he was in more heroic parts in prior movies, but unfortunately The Power of the Whistler suffers somewhat under its rather belabored plotting, despite a very good mystery setup and a “whirlwind tour of New York” structure. Also, content warning, there are several animal murders, all of which take place off screen but several of which are pretty upsetting, nonetheless.

With Castle not only back in the director’s chair but also co-writing Voice of the Whistler (1945), I had some hopes for this fourth installment in the series but, unfortunately, it is little more than a perfectly serviceable noir melodrama about greed and a love triangle, albeit with a nice lighthouse setting. For a movie that’s only about sixty minutes long, it takes its time getting to the inevitably tragic denouement, which seems to come together – and then come apart – pretty abruptly.

Once again, Castle showcases his aptitude for economy, especially in the film’s newsreel opening, which sets up all the backstory we need – and then some. Like all the films in this series, Voice opens with the Whistler’s shadowy presence introducing the story and narrating what we’re about to see, and while much of the rest of the film may be lacking in atmosphere, the image of the Whistler’s shadow gradually climbing the seaside rocks is a potent visual to start us off.

Mysterious Intruder (1946) is, unfortunately, the last of these films to be directed by William Castle, but at least he goes out on a high note. Screenwriter Eric Taylor’s other credits include several Universal horror pictures, among them Black Friday, The Ghost of Frankenstein, Son of Dracula, and the 1943 versions of both Phantom of the Opera and The Black Cat. He provides story and screenplay for Mysterious Intruder, which feels more like an unrelated script that was repurposed as a Whistler episode than any of the others so far. While the Whistler still provides his usual narration, including occasional interludes, he interacts less directly with the characters, and never interferes with the plot, as he has in a couple of prior occasions.

Luckily, Mysterious Intruder can stand pretty well on its own. This time around, Dix plays an unscrupulous private eye who is hired to locate a young woman for mysterious reasons. Those reasons become obvious fairly early on, but they provide a good MacGuffin to drive the plot and prompt the various murders that inevitably follow.

Five movies into this series, I think I can safely say that Dix is at his best here when he’s allowed to play a bad guy – or at least, someone who isn’t entirely above board. While he may go a bit over the top with his sleazy detective, prompting one to wonder why anyone would ever trust him, he’s got a lot more energy here than in many of his prior performances.

For The Secret of the Whistler (1946), Castle is replaced by George Sherman, who has no horror bona fides to speak of but who directed an absolute pile of low-budget Westerns. Story and script, this time, come from Richard Landau (who worked on The Quatermass Xperiment, among others) and prolific silent-era screenwriter Raymond Schrock, whose more than 150 screen credits include the Lon Chaney Phantom of the Opera and The Hidden Hand.

Dix is playing a bad guy again, which is nice. He’s an artist whose career is being financed by his marriage to a wealthy woman who suffers from frequent heart attacks. Unfortunately for everyone involved, he falls in love with a gold-digging artist’s model (Leslie Brooks) and figures he needs to get his wife out of the way – but she won’t accommodate him by kicking off fast enough, so he takes matters into his own hands in a familiar but effective bit of gothic melodrama.

Continuing the string of prolific but less illustrious directors, the seventh Whistler film is the last project from director William Clemens, whose CV is pretty much nothing but programmers of this sort. From a story by émigré mystery writer Leslie Edgley, the 1947 movie is inexplicably titled The Thirteenth Hour, despite the plot having nothing to do with time at all, let alone a particular hour, thirteenth or otherwise.

It’s also the last film (full stop) to feature Richard Dix in the lead, or anywhere else. Suffering from a heart condition, he was unable to appear in the eighth and final Whistler film in 1948 and he was dead at the age of 56 by the end of September, 1949. He’s fine enough in The Thirteenth Hour, even if he is once more shackled with a sympathetic good guy role, this time playing the owner of a small-time trucking firm that gets caught in an unlikely frame up.

Because of Dix’s departure, the only thing to tie The Return of the Whistler to the previous films is the presence of the Whistler himself, still voiced by Otto Forrest, and still providing his usual sardonic narration. The story is another taken from Cornell Woolrich – this time his 1940 short “All at Once, No Alice” – meaning that it enjoys a tighter plot than many of the other Whistler pictures.

Michael Duane (who was only in, like, seventeen movies) plays a young man whose bride-to-be (Lenore Aubert, later in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein) disappears on what was to have been their wedding night. Shortly thereafter, he runs into a private detective named Gaylord Traynor, played by the extremely prolific Richard Lane, who managed to tuck some 180 screen credits under his belt while also working as an early TV personality doing sports announcing for television station KTLA.

Directing duties this time come from D. Ross Lederman, another prolific helmer of B pictures who would move on to directing mostly Western TV shows in the ‘50s. According to the internet, Lederman was known for delivering films on time and under budget, which is believable given the overall workmanlike quality of the picture – not that many of the other Whistler movies were exactly arguments for the auteur theory or anything.

Ultimately, though, workmanlike or not, Return of the Whistler is one of the better Whistler pictures and, fundamentally, all of them are solid, enjoyable noirs. There’s nothing here that’s a forgotten classic or destined to become a new favorite, but it’s nice to have them around, and it’s great, as always, that Indicator is doing the work to preserve some of these B-roll pictures. The only bummer is that these are region B encoded, so folks in the States will need region-free players to enjoy them.

Regular readers will know that Indicator is one of my favorite boutique labels and, as always, the restorations here are good throughout, the packaging striking, and the Blus are accompanied by a handful of interesting extras. Plus, there’s eight films crammed into this boxed set and, even at only around 60 minutes each, that’s a whole lot of “strange tales” from the Whistler.

———

Orrin Grey is a writer, editor, game designer, and amateur film scholar who loves to write about monsters, movies, and monster movies. He’s the author of several spooky books, including How to See Ghosts & Other Figments. You can find him online at orringrey.com.