1966

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #175. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Kcab ti nur.

———

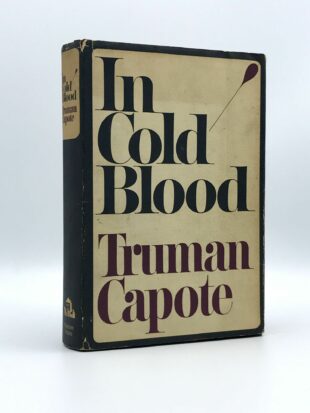

Come one, come all, this week we’re swinging our way back to the ’60s and to the progenitor of modern true crime – Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood.

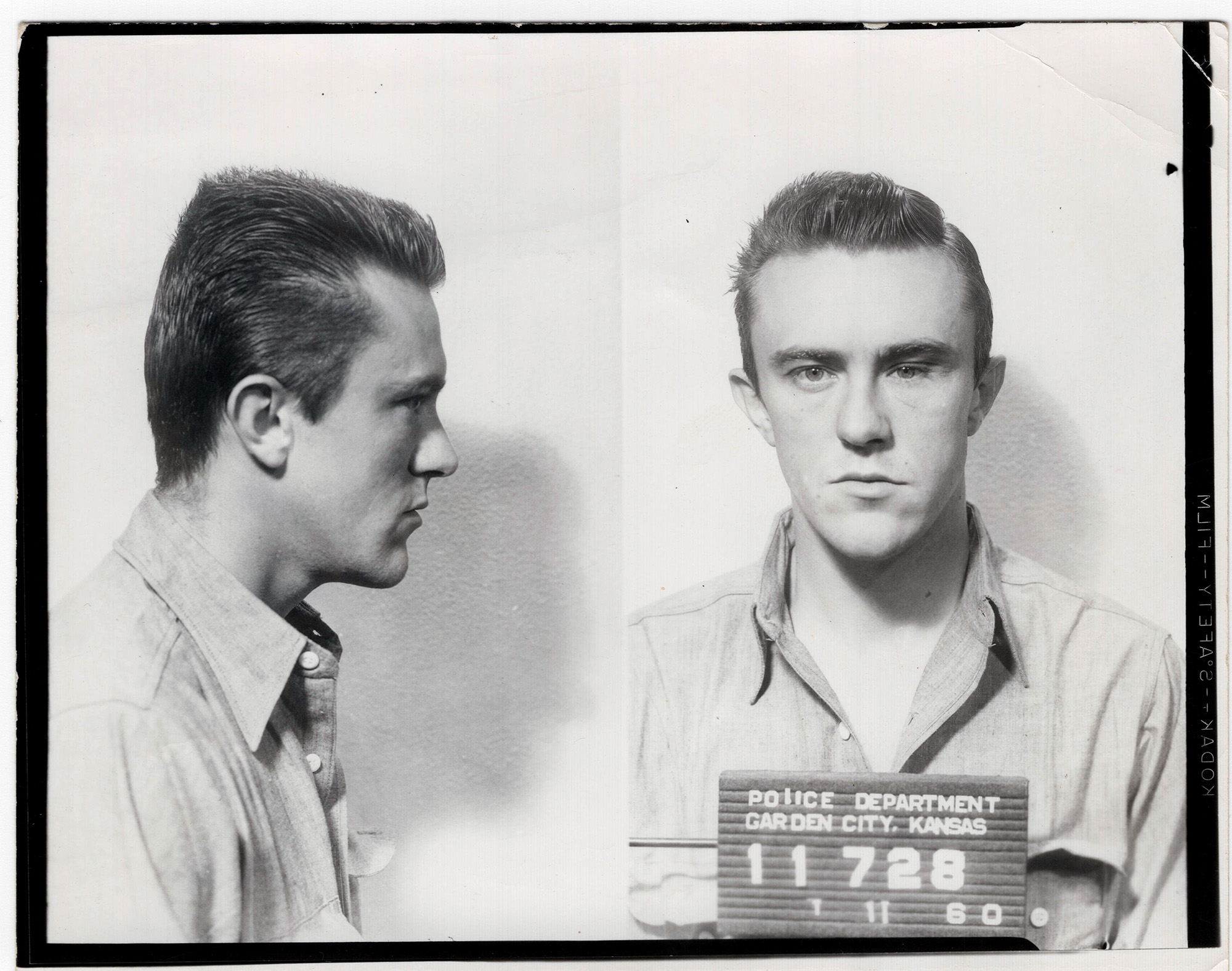

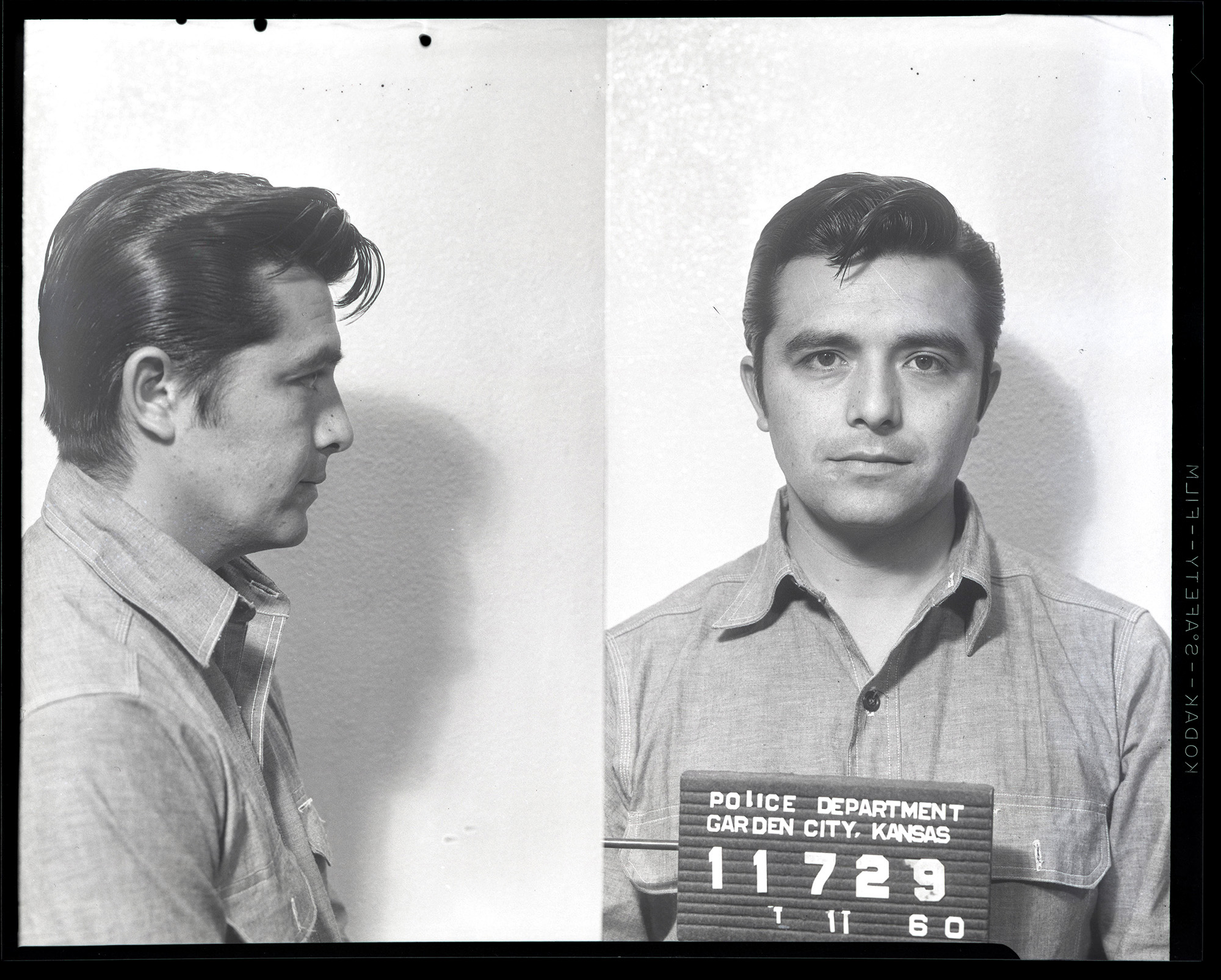

In this book, written at the same time as the events it follows, Capote writes about the surprise murder of a family in a sleepy town in Kansas and the eventual prosecution of the perpetrators: Richard Eugene “Dick” Hickock and Perry Edward Smith. The book posits itself as an immaculately true work of journalism; later testimony and writings seem to suggest that Capote fudged at least some of the details for dramatic effect. In any case, it was a tremendous financial success which launched the true crime non-fiction novel into being.

No-one really understood how hard she worked on this stuff and it was beginning to really get on her last nerve. She could ruin these people! She caught every stutter, every blue joke, every little side-bit about how badly they wanted to see what was in the pants of the latest killer or chief of police or whatever. She had the power of life and death in her hands and yet she was still getting snippy slack messages about the audio issues caused by her bosses not knowing how to use a mic! Why couldn’t she have found a different internship?

This is one of those books where it could only have been written by a gay guy. And it’s not solely because of the text’s dripping homoeroticism that comes through every description of these killers who are constructed with a dark charm. It’s also not just because of Capote blatantly having a thing for Perry Edward Smith, fixating on him with a fetishistic lens we will explore later. No, the real gay touch of the book is the incisive outsider perspective.

Much like Isherwood, Capote’s writing relies on a gay fly-on-the-wall positioning. He’s non-threatening enough to be allowed in these spaces to explore the interiority of everybody’s lives, but still detached enough to see the constructs for what they are. In the general news coverage of the murder of the Clutter family, the shock lies in that the greatest institution of American Christian life has been desecrated – the nuclear family and their land are no longer a safe haven. To unpick the cultural moment happening here requires someone for whom the promise of safety in the American Protestant family unit has never been guaranteed. In this, I also end up thinking a lot about the work like James Baldwin’s If Beale Street Could Talk or Evelyn Waugh’s A Handful of Dust, where gay writers take the scalpel to normative social relations and explore the fractures that lie within.

For this outsider position to be key to the novel which functioned as the genesis for our modern era of narrative True Crime, makes it more fascinating that the focus has now moved away from the outsider and to work being created people who are very much inside. Instead of having an uneasy relationship with the Normalities foisted upon us, they are fully embedded in them. Instead of getting deep insights into what happens when a fantasy crashes into the daily realities of violence, we are told that there is something real to be mourned beyond that goes beyond the lives lost. Made by the insiders who most benefit from the myths of safety in Property and Family, these bastard children narratives become paranoia machines, instilling the panic that there is a killer round every corner, reinforcing the swirl of emotions and worship of securitization rather than interrogating it.

These men had come before. She bore the marks, they bore the bullets. The warning call had come so now she had 15 minutes. 5 to dress herself, pull gloves over calloused hands and make cloth stretch over heaving power. 5 to get armed to the teeth. 2 to look at herself in the mirror, trace the lines of ache from her brow to her chest. Half a minute to wonder why these men wouldn’t just stop. Another half with a war cry to shout the desperation away. 2 to slot into position.

It is important to this book that the killers are darkly romantic figures of a uniquely American variety – drawing on the outlaw narratives that are central to the country’s masculine ideals.

One of the killers, Dick Hickock, is a man who in another life could’ve been an all-American hero. However, through a mix of a debilitating car accident and a long series of subsequent bad decisions, he became increasingly violent and cruel. In a different book, the writer would focus on this fall from grace as a grand tragedy. He could be the lead of one of the spaghetti westerns that were contemporaneous to In Cold Blood’s release – a charming white outlaw but for Capote, Hickock is essentially the devil – and not quite in the semi-sympathetic Miltonian sense. His silver tongue is not a thing of roguish charm but pure evil. At the same time, the author still finds an eroticism in their dynamic.

It is clear Capote is more sympathetic towards Perry Smith – through a mix of outsider kinship, racial fetishization and the lure of cosmic tragedy present in both his writing and his own life. When describing Smith, the text is often florid and dreamy. For Capote, this is a dreamer ruined by the harshness of reality, ravaged by war and trauma. What also can’t be ignored here is how much he is pulling on the racial position of Smith for this characterization. Capote fixates on the texture of his hair, the tone of his skin, persistently highlighting the mixed nature of his heritage and constructing his general disillusionment as a racial one. While it is certainly true that Smith’s Indigenous heritage complicated his life and relation to society, it is also fairly clear that Capote far too heavily overidentifies himself with Smith’s lonely outsiderness in a way that veers into fetishism. Specifically, he pulls on ideas of the noble savage to paint a portrait of Smith where he is a being of impulse and strong feelings with noble morals (notably emphasizing him saying “I despise people who can’t control themselves.” and being disgusted at his co-conspirator), manipulated rather than ever really deciding to do something terrible.

Having these two as the central figures demonstrates the contradictions within the mythic figure of the American cowboy. An icon of whiteness but often embodied by non-white people and cultures – the word cowboy descending from “vaquero.” An icon of hegemonic masculinity but lionized for being detached from ties to the traditional family – something Hiram Pérez writes extensively about, specifically how this dissonance is queer even when the cowboys themselves weren’t always engaged in same-sex behaviors.

These foundational outlaw erotics also bleed through to contemporary true crime and its fascination with serial killers. Lone figures (usually men) with troubled pasts and tragedies aplenty leading up to their acts of violence. You can see this with Ryan Murphy’s series on Jeffrey Dahmer, and also more broad true crime podcast conversation and also memes around the killer where his (structural) Desirability is so often placed front and center. There is a reason why Dahmer becomes a darkly romantic fixation, where John Wayne Gacy becomes an abhuman entity (within Murphy’s series and more broadly) despite both of them doing heinous evils which to a greater or lesser extent involved children.

Glass towers loom over the spot where the boy turned blue. On Aaron’s daily walk he always goes past it but never through, and so does his Pitbull Rusty. He couldn’t quite remember which one of them started the tradition, the ritual avoidance, respect or fear for an arbitrary piece of pavement. He wondered if the ritual would die with him, or hold on forever, like wolves know to howl at the moon

True crime (particularly that involving murder) generally relies on the idea that there are some harms that shock us and others that don’t. Specifically in the case of killers, the dead become a vessel through which we can explore troubled minds. To be fair to Capote, he does try to give us a full and embodied understanding of the family and their complexities before their deaths. But it all still mostly feels like a purpose for the violence and tragedy.

As above, what makes these deaths so shocking is that they break the supposed safety of the home but also the deceased were nice and white and classed. But what most of us who exist on the margins can recognize is that this Security, however temporary or fleeting, only ever existed for a tiny few. To paraphrase William C Anderson – some of us are always at war.

At the same time of this book being written and realized, the Civil Rights Movement had peaked and was soon to be falling. Malcolm X had been killed, the authorities continued to increase their surveillance and harassment of movement leaders. Despite the passing of legislation, people were continuing to be martyred for engaging their basic rights. The Vietnam war was ramping up, with more and more people killed in the name of imperial interests. This is the context in which this novel pioneering the modern genre and its understandings of death must be understood. That to the target audience those deaths were distant and perhaps even expected or worst of all deserved. But the Clutters at what shakes the nation.

More contemporaneously, I think about Tony Hughes and his presentation in the aforementioned Murphy series. He is the main victim who gets humanized and has time allocated to his life. Hughes was a Black deaf man and also happened to have been one of Dahmer’s longer relationships with a victim. At points the portrait is really powerful, but it does repeatedly veer into using his disability to produce pity from non-disabled audiences, rather than using it to highlight the way he (and other disabled people) are made particularly vulnerable to violence. In general, I think the direction and performance also over-rely on Hughes’ niceness bordering on infantilization to beatify him. I think the lean towards pity based on disability betrays the reality that Black people have to be extra-innocent to not be seen as walking corpses – even in a genre (and at this point an industry) whose leaders will often claim that victims are at the center of their work.

Ultimately the cruel truth is that if Hughes had died of AIDS, had died in gang violence, had died from addiction, had died from suicide, had died from any other issue allowed to run rampant by the state, he would just be another dead Black boy for the pile. In the context of true crime and white America’s relationship with Black death, his death is only relevant because it complicates the narrative of the eroticized and enigmatic “Monster” who killed him.

Maybe the most difficult thing is that despite all of my criticism In Cold Blood is still a deeply compelling novel when you’re reading. I knew it was extremely unethical, and far more interested in poetics than journalism. I knew (and could tell while reading) Capote was very intentionally playing favorites in his portrayals of the characters. However, it’s hard to deny the beauty of Capote’s dreamy vision of sleepy towns and tortured killers. And in the era of endless true crime podcasts and documentaries and text-to-speech YouTube videos I wonder where the poetry has gone.

———

Oluwatayo Adewole is a writer, critic and performer. You can find her Twitter ramblings @naijaprince21, his poetry @tayowrites on Instagram and their performances across London.