An Attempt Against Muscular Demonstrations of Power: Child of Light at Ten

This is a feature excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly #175. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

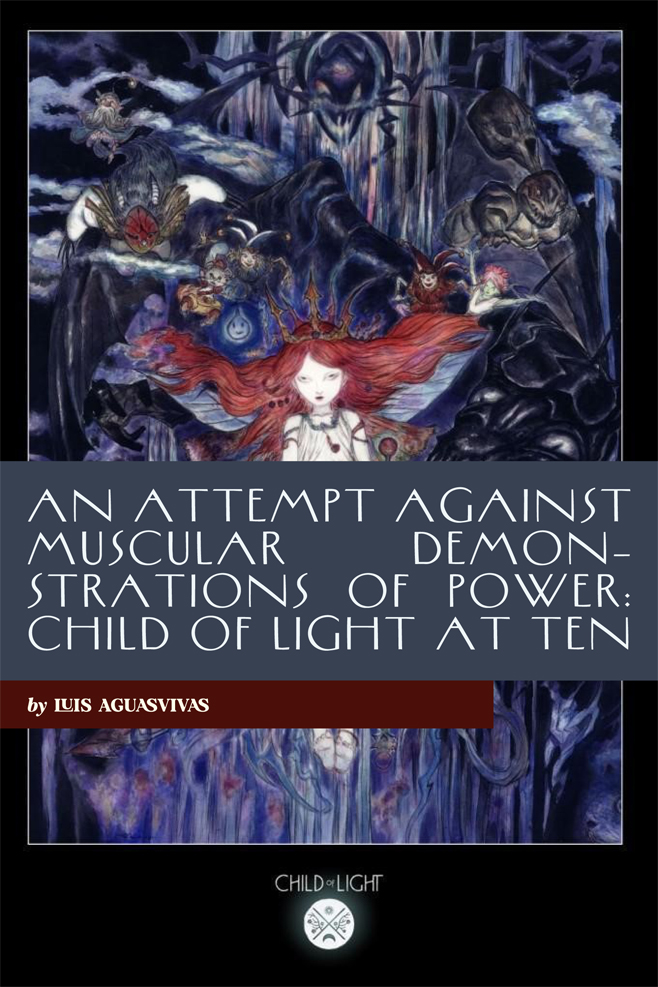

There was a point where I became disillusioned with videogames. As they “matured,” videogames began to feel frivolous. Their morbid themes, adolescent fantasies about power and worlds full of drab color were more than off-putting. As I grew into adulthood and I began to interact with an increasingly perilous world, things like climate disasters, international crises and the shrinking prospects for the middle class became my preoccupations. I decided that I would rather waste my time with something else. Thus, from 2010 to 2017 I played few videogames. However, just one still image of Child of Light is all it took for me to want to play it, to venture into the world of Lemuria. Immediately, I saw Child of Light as a quixotic attempt by one of the biggest AAA studios.

No matter the destination, quixotic quests begin with just one bold step. In 2014, for Ubisoft Montreal, this bold step was releasing a game like Child of Light. For the game’s main character, Aurora, it’s her first steps in the world of Lemuria. Child of Light was the only game I played on release during my long spell when I fell out of love with videogames.

Its lineage is easy to discern. Its turn-based gameplay was influenced by Grandia and Final Fantasy. In a making-of documentary for the game, creative director Patrick Plourde stated that with Child of Light, he wanted to provide an experience for fans of “classic console RPGs” that can be shared with their families and loved ones. Plourde, who grew up playing games like Chrono Trigger and Final Fantasy IV, wanted to create a game that he and other parents could play with their children. This was one motivation behind giving players the option of playing the game cooperatively. One controls Aurora, a young girl on a quest to save her father, and the other, Igniculus a blue sprite. Aurora is the avatar through which we experience the world of Lemuria. Igniculus is her companion that controls like the star cursor, as in Super Mario Galaxy. A companion player can light paths, open chests, and even influence battles with Igniculus.

Child of Light, both as a game and a production process, was a soft epistemological break from prior forms of AAA development because it simultaneously pandered to an old-school audience’s nostalgia for Japanese role-playing games, while also attempting to reach a wider demographic through the game’s picturesque visuals and an unconventional story told almost entirely through rhyme. The game’s rhymed dialogue is charming, especially for fans of poetry, though it can sometimes feel forced and occasionally creates moments that are hilariously cringe. While exploring a dungeon I opened a chest and Aurora asked, “What’s inside?” and Igniculus answered her by saying, “Homicide.” I laughed out loud as a monster emerged from the chest and triggered a battle. Expect many more “forced” rhymes like this when playing Child of Light. This adds to the game’s magical charm.

A decade after its release, the whimsy of Ubisoft Montreal’s Child of Light still twinkles. In retrospect, the game was released in an era when big studios took more chances due in part to the success of the Nintendo DS and Wii, and the ubiquity of smartphones. These devices ushered in a rise in “casual gaming.” It was a time when AAA studios created smaller “artisanal” games alongside the typical big-budget fare.

Playing Child of Light for its tenth anniversary is a bittersweet experience. I’m happy that Ubisoft made it, but I’m verklempt when I consider that AAA studios and their investors do not deem a game like this worth creating in 2024. The industry now finds itself trapped in a curse of its own making, brought on by the shortsighted embrace of criminally expensive productions. Those in top level positions dictate that the same game to be made over and over again. This shortsightedness is apparent considering that Child of Light was released at the beginning of Gamergate in 2014. Unfortunately, with vile voices again decrying diversity in videogames, our spunky protagonist Aurora, the world of Lemuria and its inhabitants might be moronically perceived as “forced diversity” by fanatics, chauvinists and quacks seeking to clout.

Videogames cannot be discussed devoid of context and the historical and material conditions in which they are produced. Doing so dilutes their intrinsic value. I, for one, view videogames first and foremost as cultural artifacts imbued with meaning. Call me naive, but the type of games that AAA studios prioritize engenders certain passions in fans. These fans are the same ones decrying diversity in games, and seek a sort of perverse fantasy life that validates them, one that is devoid of meaning and poisons all that come into contact with it.

Around Child of Light’s release, Bastien Alexander, a creative consultant for Cirque Du Soleil Media who also helped in the game’s development, described it as “a breath of fresh air in a world where most videogames are based on muscular demonstrations of graphics and power.” Alexander’s statement was astute back in 2014 and is still relevant today.

Creating the world of Lemuria, like the process of creating games in general, was an extraordinary collective undertaking by a team of around 40 people at Ubisoft Montreal, an unusually small number. For this team, the production differed from other games they worked on. Recalling her experience while working on the game, Brie Rose Code, the game’s lead coder, stated the team had the highest morale of any other she worked with at the time. One-third of the team were women (a total of twelve). According to Plourde, this was the “biggest ratio ever” at the time for any Ubisoft project. For Code, who stated in the game’s development diary that, “representation in media is very important,” this is one of the reasons morale was so high.

Code goes on to add, “And so it has been such a pleasure and an honor and a dream come true to work on Child of Light. I love the character of Aurora. She’s brave and tough and relatable and girly and cute and rises against adversity. She’s an interesting character. And all of this is beside the fact that people in real life are just so interesting and so varied. People are fascinating. And in games, we are making virtual worlds, and so we can make anything we want. I think we have a responsibility then to create interesting, varied characters.” The increase in different perspectives contributed to Child of Light becoming a game full of tenderness.

In a GDC talk in 2013, Plourde laid out his vision for Child of Light as feminine, exotic, mysterious and dreamy. He admits that the game was a tough sell at first since Child of Light “doesn’t have a lot of hot business buzzwords. Small is not a virtue,” the game is “not free to play” or mobile and when the game was proposed to higher-ups Japanese roleplaying games were “not sexy.” Infamously, in 2012 Fez designer Phil Fish tactlessly said of Japanese games that, “they suck.” This was not just the opinion of one individual but a more widely held belief by Western designers, executives and players. Plourde was able to get approval for Child of Light because he had a “stockpile of bargaining chips” from his work on several projects at Ubisoft. Coming back to the present, it’s difficult to imagine many creators today in AAA studios having such a stockpile to leverage in order to make another such game.

Child of Light is a progenitor game of sorts. It was part of a larger revival and interest in Japanese roleplaying games. Sabotage Studio’s Sea of Stars and Square Enix’s recommitment to old-school 2D RPGs with games like the Octopath Traveller series are indebted to it. Child of Light wore its influence on its sleeve for all to see one year before the release of Toby Fox’s indie darling Undertale. The fact that a Western AAA studio made a game inspired by Japanese roleplaying games back in 2014 made an impact. The game’s developers were made into a core team at Ubisoft Montreal, showing that games like this had a future in the AAA industry outside of Japan.

———

Luis Aguasvivas is a writer, researcher, and member of the New York Videogame Critics Circle. He covers game studies for PopMatters. Follow him on Bluesky and aguaspoints.com.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 175.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!