Turn of the Zillennial

I boot up my PC and the booming chimes of the Windows XP startup noise shake my desk. Homework be damned, I have to check AIM. Maybe Emily is on.

Released in 2015, Kyle Seeley’s Emily is Away captures the experience of aging apart from those you once held dear. Perhaps most notably, it’s a nostalgia drug. You experience this visual novel through what seems to be a Windows XP emulator, fully equipped with AIM – your primary form of interaction with the game. All your friends are here and their buddy pages are littered with Red Hot Chili Peppers and blink-182 lyrics. Welcome to 2002 and the blast to the past you’ve wanted, you Millennial freak.

Anyone else remember when it was cool to hate on Millennials? I flash back to high school, where I sit uncomfortably at my desk as my teacher delivers another of the all too proliferated “avocado toast” tirades. I’m ruining the economy, I’m too lazy to work, etc, etc… I don’t think Ms. Economy ever saw the futility of blaming teenagers for her woes, but that blame stuck with my classmates and I. We weren’t liked.

In Emily is Away, none of that matters. The game doesn’t progress further than 2006, when the median Millennial is graduating high school. The 2008 Housing Crisis hasn’t hit yet and things seem peachy. Nobody will say a thing about avocados to you in this game. It’s better than the nostalgia trip you desire – it’s safe.

Since my birth in March of ‘97, I’ve been accused of everything: I have killed every industry from mayonnaise to marriage and my bloodstained hands are eager for more casualties. My barbarity will come for all economic sectors and by now the most astute reader has realized that I’m not a Millennial. If we go by hard cutoffs, I missed that boat by three months; the Pew Research Center says so. I’m firmly and definitely part of Gen Z.

So, I mean. What the hell?

Generational demographics are largely meaningless, but they’re how the world tells us we should be defined, and they in turn help shape our identity. For twenty-seven years the world has told me I’m a Millennial and that the majority of things happening are my generation’s fault. They’re scapegoat tactics, but I fit the role of that goat, and so I became the goat. Maybe I should feel overjoyed that I can shed that skin; instead I feel invalidated. Part of my identity no longer belongs to me.

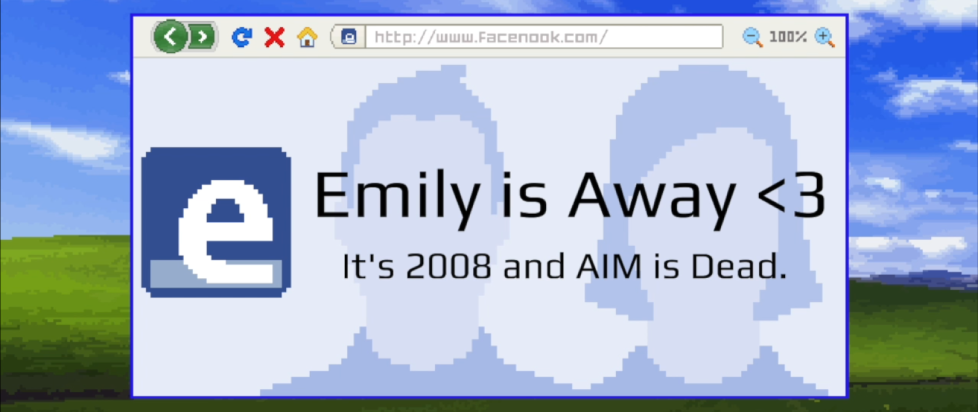

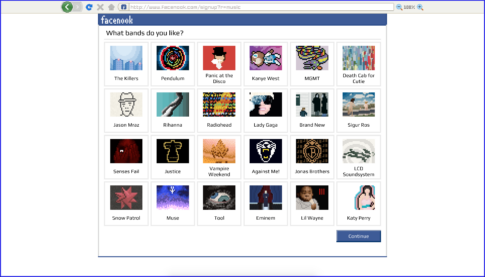

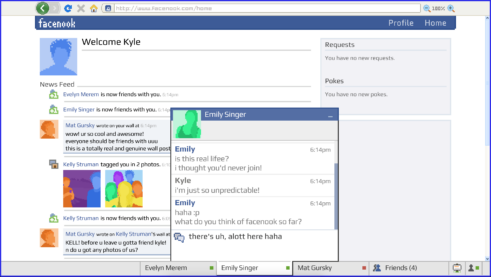

Emily is Away <3 (the third game in the series) proudly claims “it’s 2008 and AIM is dead.” eschewing the time of buddy icons for a fresher nostalgia: Facebook. The gameplay and even plot beats of Emily is Away <3 remain largely the same: it’s still a story about getting older and losing friends as a natural consequence. This feels unique. As a franchise evolves, it often takes advantage of newer technologies to tell new stories and innovate upon existing mechanics. With Emily is Away, the evolution is symbiotic; new communication platforms facilitate the means of growth in the series. Here, it’s a lot more subtle than Otacon saying “We’re on PS3 now!” but the point remains the same.

This creates an interesting opportunity for my identity crisis: if the timeless idea of aging away from friends remains the same, I can simply identify if I connect more with one game’s communication platform over the other. AIM seems inherently linked to the Millennial experience, it follows suit that Facebook would appeal more to those in Gen Z. Considering I made a Facebook account around 2008, the time the game is set, I seem predisposed to relate more to the third game. This should be an easy reconciliation.

Dear Reader, it was not.

The Emily of the third game is not the same Emily I fell in love with in the first. The media that the game uses for nostalgia bait feels foreign. This isn’t my game. It’s not my lived experience. Dude, where’s my blink-182? This didn’t help me reconcile anything, and I can’t turn to Emily is Away Too for any further exploration because it also utilizes AIM as its platform.

This somewhat meaningless identity crisis shouldn’t cause this much turmoil, yet it does. The age of social media brought pedantic bigots chastising me daily for being a Millennial. The avocado toast attacks were aimed at me. I felt spurned and rejected because of my age, so I spent my time in the trenches defending my lived experiences. I spent my whole life being told I was that one thing, and justifying my existence as that thing, only to reach adulthood and be told I’m something else entirely. Something I’ve never related to, something foreign to me. We live in a world of labels and none belong to me. I say again: I feel invalidated. You don’t forget being a scapegoat, and part of that lies in my identity – and it’s much harder to shake off a part of your identity societally prescribed to you.

I boot up the first game again in a desperate search for answers. Maybe Emily is on.

In my haste for clarity, I do something I’ve never done before: I’m a lot more curt with her. I give less thought to the music I say I’m into, or what plans we make. I, for all intents and purposes, am a dick this time around. I triggered for the first time what the wiki calls “The Bitter Ending”. The only message you receive from Emily in the last chapter is “I don’t want to talk right now.” before the game ends. It stings – I’m assumably a different person every time I play the game, but Emily always feels the same. To hear such a blunt diffusion from someone I love will always hurt. Still, I realize something. This ending is no different than the more common one, where you feel the slow pain of a friendship dissolving in real time. You and Emily have still wound up strangers.

Regardless of any of the choices made – whether you like Coldplay or not, or go to Brad’s party – this is always how it was going to end. The identity you create doesn’t matter. What stands in place of my crafted persona are the experiences I had. The joy as Emily hinted she maybe had feelings for me. The heartbreak I felt as she grew distant. These are the things I remember most about the game, not Brad’s party (something the game doesn’t even show you – a party doesn’t happen over AIM).

This is the real lesson of Emily is Away and the series as a whole. It isn’t a statement that over time, friendships fade. It’s that the experiences you have with them are vastly more personal than who you were at the time. You can craft your identity however you like: you can do it over Facebook, AIM, or in the real, physical world. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter, life will still happen. Nothing will matter more than the things you do. That’s what you’ll remember; that’s what defines you.

Pew Research Center be damned – I’m a Millennial. I’m not a Millennial because of some artificial age bracket, or because I spent my life being told I was one. I’m a Millennial because of every time I had to defend my place in this world from those who would say that the time of my birth prescribes my fate, personality, and desires, without any consideration for the actual life I’ve led. Being a Millennial is a badge I earned and it’s one I’ll wear with pride. These are my lived experiences. This is my game. This is my Emily.

———

Perry Gottschalk is a damn proud Millennial from Chicago, thinking about games and the way they make us feel. For more feelings, follow @gottsdamn on Twitter and Instagram, and @gottsdamn.bsky.social on Bluesky.