A 16-Bit Memorial Garden

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #173. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Analyzing the digital and analog feedback loop.

———

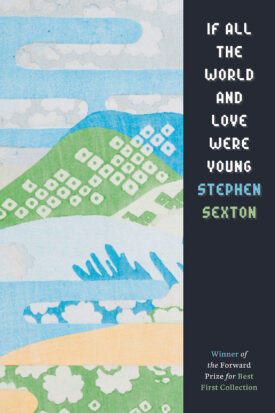

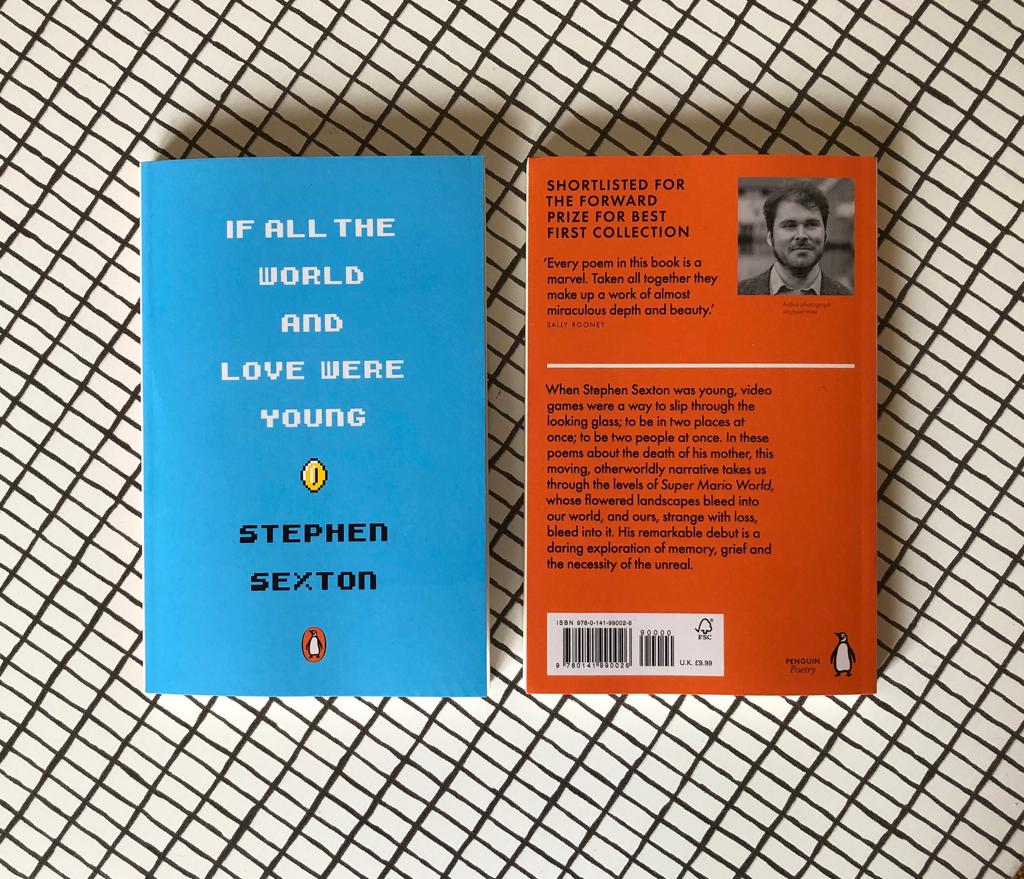

Last month I had the wonderful opportunity to review Wake Forest University Press’ reissue of If All the World and Love were Young. Penned by award-winning Belfast poet Stephen Sexton in 2019, the title references a line from Sir Walter Raleigh’s “The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd” and is a parodic response to Christopher Marlowe’s pastoral poem “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love.” Despite the classical nature of this reference, the wistful yet disenchanted tone of Raleigh’s poem reveals the postmodern attitude that Sexton writes in. Not to mention the self-referential and eclectic subject matter of his extended poem.

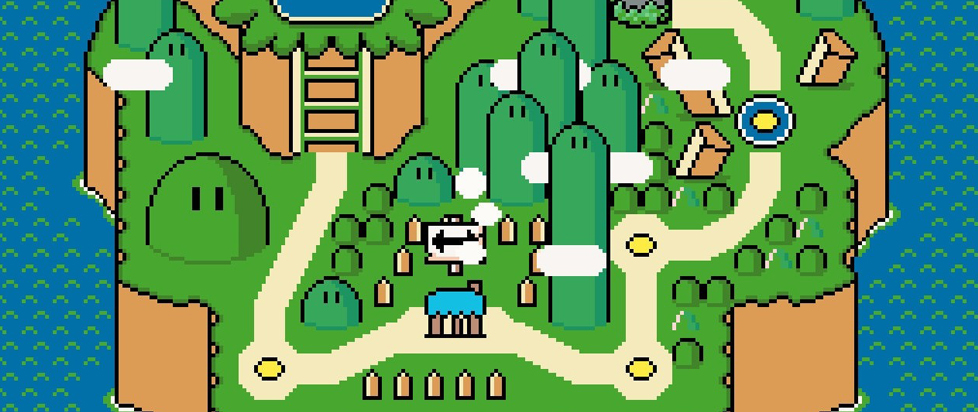

The piece gained renown for being a literary memorial for his mother, mapped onto the abstract pop-culture geography of Super Mario World (1990). Finally getting the chance to read this work, I can confirm that the framing of this poetry book is not at all a gimmick – it’s a sincere and perceptive choice. One could even call this framing transgressive in that it effortlessly blends high and low culture (as much as I loathe those terms). For Sexton, death and Super Mario World have always been connected and he gets at this connection via tracing the long chain of signifiers he’s experienced since childhood.

To be clear, Stephen Sexton is not the first to write videogame-related poetry. People have been writing poetry related to their gaming experiences on the internet for decades. In recent years, poets like Rachel Atchley and Latonya Pennington regularly contribute poignant work to Videodame and Into the Spine, respectively (as I’m sure they do elsewhere). Various game designers have also developed games that directly reference poetry, like Dejobaan Games’ Elegy for a Dead World which is a dedication to the British Romantic tradition. There are also games that are visual poems, like Jordan Magnuson’s Walk or Die which shares a similar surreal tone to Molleindustria’s Every Day the Same Dream. The latter being a title published all the way back in 2009, I should add. Magnuson, as of last year, has even released an entire book on Game Poetics, which he has made open access.

Only recently have there been more attempts at developing a poetics that is both unique to games and places games within the ongoing literary history of poetics. This is what Sexton has accomplished with If All the World and Love were Young. This extended poem is not only a stunning elegy for his mother, but an ekphrastic piece about the nature of play and memory. One that establishes a poetics not just of gaming experiences, but one that recognizes the physical media of games as poetic objects in and of themselves.

For instance, early in Part One of the extended poem, Sexton devotes the opening lines in “Yoshi’s Island 2” towards the aesthetics of both the what he saw as a player on his television and the physicality of a world on-screen:

“Pixels and bits pixels and bits their perpendicularity:

One of the worlds I live in is as shallow as a pane of glass.”

Notable as well in these lines is how he positions himself as both the viewer and the player character of Mario, a dual mindset we are often subject to when engrossed in a game world.

What Sexton has done with If All the World and Love is Young is demonstrate how games are both physical technology that enable a postmodern experience of witnessing and making meaning. The representational media nested within that technology engages players with ever-evolving audiovisual signifiers and makes them actively part of that process of making meaning as well. And as long as you have a working outlet and a compatible television, us players can find and make meaning in a variety of different settings. Sexton’s prefatory note to his extended poem is a perfect example of this, where he describes playing Super Mario World in his late 1990s home (emphasis mine):

“My back is to the camera. The television was positioned so it faced out from the corner of the room where the wall met the patio door. To my left, I could see the garden, along which a little river ran and, over the fields, a dense forest. To my right, there was the huge block of the television, which was already fifteen or sixteen years old. My eyes drifted between these two positions. Because of the flash of the camera and the glare of the television screen, it’s impossible to tell which of the following levels I’m playing.”

Games blur the boundaries between personal and shared histories, individual and collective states of consciousness as well as private and public spaces. It’s no wonder then that one of Sexton’s epigraphs is one of Susan Sontag’s influential thoughts on photography and the overlap of self and the construction of a perceived self. Sontag’s On Photography famously explored how photographs were also, like games, both objects and complex containers of cultural signification. She also, like Sexton, realized how the act of photography was also an organizing principle of human thought. Both photography and games have proliferated to the point of influencing our everyday routines and perception of communication.

What Sexton has demonstrated deftly with If All the World and Love were Young, is that our game experiences and memories are viscerally entangled with mundane locations. Each and every one of us players likely have specific individual anchoring memories connected to a specific title or perhaps a play date with one of our friends. Often these moments are fragmentary and not specific to what’s on-screen, as game critics and theorists have noted. Despite how absorbing playing games can be we are paradoxically more aware of where we played or who we were playing with.

In his essay “No Traces” for Critical Hits: Writers Playing Video Games, Sexton recounts some of his most intimate game memories and the key players and events involved in those memories. The first memory and the one tied closest to his poetry collection is of him playing Super Mario World in the summer of 1998 at his County Down home. The same summer that the Real IRA planted the Omagh bomb in protest of The Good Friday peace agreement that was to end the conflict known as the Troubles, which claimed 3,500 lives since the late 1960s. Sexton remembers hearing of the Omagh bombing on the radio and later learned of further details of the disaster from TV news.

He goes on to explain how a childhood friend of his played Metal Gear Solid with him and that in the act of playing and witnessing a game together, he would often forget who held the controller. Later in his life he read literature about games as visual culture objects and stumbled across a term used by scholar Peter Buse, the “circuit of specularity,” which eloquently described the vicariousness of playing games. Gaming, whether alone or with an audience, makes the player aware of seeing themself seeing themself. You transcend and I would add, in some instances, extend your perception of your identity and body as you imaginatively inhabit game worlds.

Sexton is keenly aware of how technology has constantly been mediating his everyday life since early on. His locus of game memory is fixated on both his old childhood home in County Down and the photographic representation of him playing Super Mario World in that home. The photograph, taken by his mother in that same timeframe mentioned in “No Traces,” serves for him as an edifying tool for making sense of his mother’s passing. At first, he struggles against the photo’s memento mori quality, focusing instead on the nostalgic turn towards the past and a home and a self that no longer exists exactly as it was captured.

Sexton draws a parallel between this realization and his observation in “No Traces” about games operating in a similar manner to photography. Specifically, games as they are experienced on consoles, which themselves are quite possibly becoming obsolete. Contrasting “the vast, coin-hungry machines of the arcade,” very much a public space for gaming, consoles “put the experience of gaming into domestic spaces.” This led to games becoming signifiers of “home, and the moments of childhood one rapidly outgrows” similar to how processors develop rapidly. As such, although games are not necessarily stationary visual cultural objects like photographs are, they are “fixed in technological time as well as personal history.” Sexton ascribes an almost supernatural quality to this feature of photography and games.

With regards to that last note, think of the doubling of the self mentioned in “Yoshi’s Island 2,” bringing to mind perhaps Poltergeist-like imagery of an entity pressing against the confines of the world that “is as shallow as a pane of glass” or some sort of doppelgänger. In the sequence or “level” that precedes it, “Yoshi’s Island 1,” Sexton describes his mother taking the photograph in an equally ethereal way:

“My mother winds her camera the room is spelled with sudden light:

A rush of photons at my back a fair wind from the spectral world.”

That memory was not just where Sexton became aware of the circuit of specularity (although at that point he had yet to learn of it). He describes it as “moments of watershed” that he will return to again and again, taking “the Orpheus route from one world up into another” as he characterizes his grief in one of the later levels “Vanilla Secret 1.”

Throughout the collection Sexton showcases a fearlessness of juxtaposing eclectic subjects. Irish pastoral landscapes, the beauty of broken-down old televisions, the way the names of the Koopa Kids remind him of singers like Wendy O. Williams, and how even ’90s slang in its archaicness is bittersweet. There’s a credits section that lists all of Sexton’s influences, emphasizing the eclecticism as well.

If All the World and Love were Young reminds us that games are worthy of literary analysis and that it’s not preposterous to perceive them as significant objects of our visual culture. Sexton recently wrote for the Irish Times about his follow up collection Cheryl’s Destinies (also reissued by Wake Forest University press), a collection that deals with how poetry and time have been transformed by the ongoing pandemic. He mentions that the isolation and loss of intimacy we experienced for a prolonged period during lockdown led him to consider new ways of joining disparate, perhaps even “silly” parties together to create new intimacies. Clearly the philosophies Sexton’s learned from his first poetic work have influenced him deeply and allowed him to express and process both personal and global grief.

Reading this collection was both cathartic and vindicating and I hope more players and poetry readers seek out its revelations.

———

Phoenix Simms is a writer and indie narrative designer from Atlantic Canada. You can lure her out of hibernation during the winter with rare McKillip novels, Japanese stationery goods, and ornate cupcakes.