Road House Ronin

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #172. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Wide but shallow.

———

My wife has been asking friends and colleagues alike what their favorite 25 movies are. Not the greatest of all time, but movies they hold dear for whatever reason. Some folks struggle with the question, fearing judgment for tastes established long ago but have since gone bear and bull in their wider estimation. Or they just have a hard time blowing the dust off the shelves in their mind theaters to recall the major hits. This has also let to a few incredulous exclamations of “what do you mean you haven’t seen [movie that bombed but then became a cult classic thanks to cable or whatever]?”

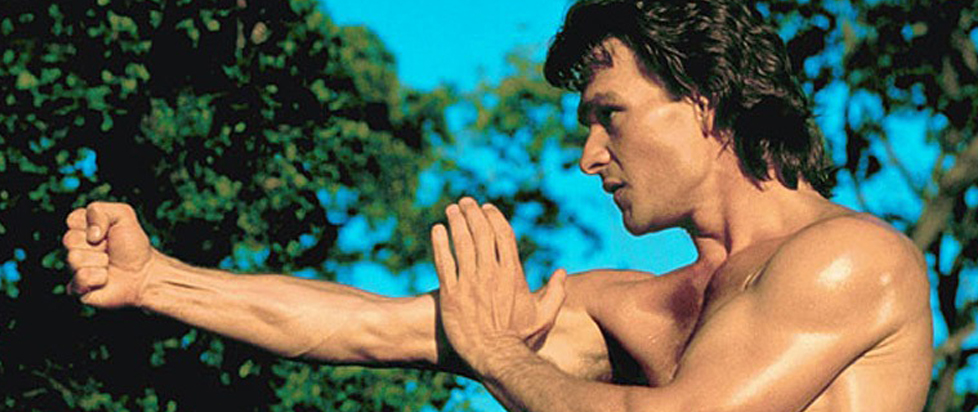

One such film was Road House, the 1989 punch-fest featuring Patrick Swayze smoking too much while squaring off with a series of small-town tough guys and then eventually a 60-year-old Korean War vet mobster. I’m pretty sure it’s the kind of movie my dad might have left playing around the house, as it featured a lot of high-heat blues riffs and sweaty kicks and ’80s toplessness, but I’d also rewatched it a few years ago and remembered it being more fun than serious without swerving too far into total silliness. So, a few nights ago, we threw it on to see how it held up, in no way influenced by the upcoming “remake” under the same title which I only just learned about this morning and am already dismissing.

Swayze’s the lead, a mysterious bouncer (or “cooler,” which is the bouncer in charge) that everyone with a lick of sense is afraid of or attracted to, and everyone else thinks they can take down. But Dalton knows that no one can beat him, which renders fighting moot for the most part. His first potential brawl is really a ruse to walk a dipshit out the door, stumbling to his car with limbs intact and smugly believing Dalton is a coward. But a rich man feels otherwise and asks Dalton to come fix up his boxing bar, the Double Deuce. Dalton negotiates a killer rate and total control and skips town that night.

If you haven’t seen Road House, you can probably predict the major beats, which are mostly that Dalton is a tough guy with a heart of gold, trying to act like he only cares about money, but can’t help but fall in with the charming residents of the town and join their battle against a cartoonish kingpin. But on this viewing, I realized there’s a bit more going on with Dalton, which is that he is a ronin, and Road House is a samurai film.

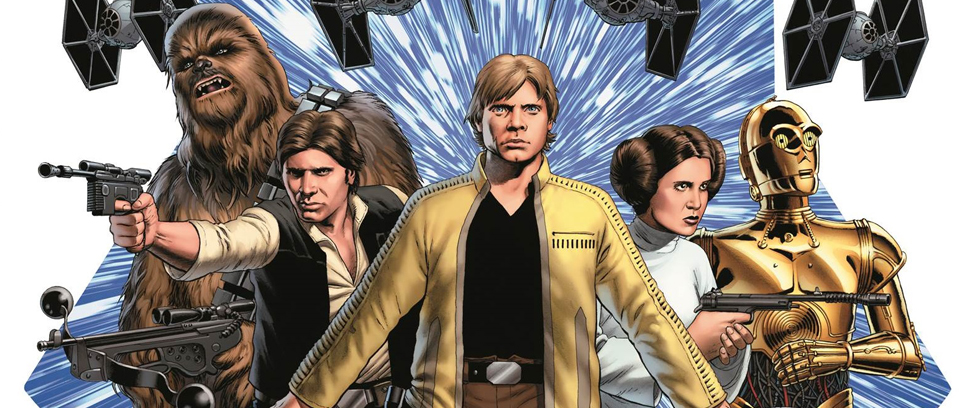

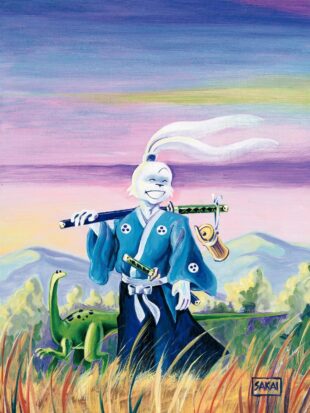

I’m no stranger to Kurosawa’s films, The Tale of Genji, and other major works of the samurai canon, but if I’m being honest, most of my knowledge of the most noble definition of what it means to be a samurai comes from Usagi Yojimbo. This comic is the lifelong work of writer and artist Stan Sakai, winner of multiple Eisner awards and, if you have any interest in comics, probably your favorite writer/author’s favorite writer/author. Sakai started Usagi Yojimbo in 1984 and has been publishing his stories ever since, with appearances alongside the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles in comic and cartoon form, videogames, even a Netflix reinterpretation. It’s the story of Miyamoto Usagi, a samurai prodigy turned masterless ronin when his lord died on the Adachigahara plain. Since then, he has wandered and done good whenever he could, only drawing his sword as a last resort.

Usagi and Dalton’s stories aren’t totally parallel, but they rhyme in a lot of ways. Dalton roams from bar to bar, taking the worst dives and violent hellholes and transforming them into places that sell booze and good times. Usagi similarly refuses to settle, instead wandering Japan on the warrior’s path in order to perfect his art. The legends of Dalton’s martial prowess proceed him, and when Dalton is eventually forced to engage in combat at the Deuce he delivers three times as many licks as he takes. Both Dalton and Usagi are underestimated, and they use this to their advantage, almost always surprising their opponents with their ferocity.

Usagi Yojimbo teaches us that a true samurai does more than just study killing – they must master various other arts, including philosophy. Dalton understands this directive, having been a philosophy student at NYU before he became a bouncer, and we see his elegant tai chi practice and affinity for reading. It also doesn’t hurt that he’s close friends with the Double Deuce’s house bandleader and can appreciate some well-played blues. Dalton also has a grizzled teacher named Wade, played by baby silver fox Sam Elliott, who is the best in the bouncing business, pairing nicely with Usagi’s Sensei Katsuichi, a seemingly invincible old lion hermit who lives in the mountains and takes Usagi on as a student only after Usagi proves his dedication. Katsuichi and Wade consider their students to be fools, though they deeply care for them as well.

The best evidence of Road House as a samurai movie is when Dalton is training his new staff at the Deuce. He fires the hotheads and the drug dealers and tells the rest that fighting should be their last course of action – they should always “be nice” no matter what a rowdy patron says or threatens. Usagi was similarly trained that the sword is the soul of the samurai, and more so, the sharpest souls are kept inside their scabbards – a riddle that Usagi struggles with as a student but comes to understand more and more with each life he takes. A true warrior recognizes her abilities, but also that life is sacred, a lesson Dalton learned when he killed a man in self-defense over a misunderstanding with a lover, leading to Dalton ripping the attacker’s throat out.

Here we see Dalton the samurai at his peak. Though he abhors violence, violence is his tool, his trade and his burden. He uses it only when pressed and aims to prevent death, laughing off the regular vandalism of his car at the hands of frustrated small-time bruisers. But mobster Brad Wesley delights in unrepentant destruction and cruelty, sending his bloodthirsty henchman Jimmy Reno out to kill Dalton’s friends, which drives Dalton to the edge. In a bareknuckle beatdown on the riverbank, Dalton and Reno seem evenly matched, and slowly Dalton realizes that Reno will not stop attacking his friends and cannot be reasoned with as he desires only brutal death. So, Dalton unleashes his throat-ripping technique while his doctor girlfriend watches aghast. The samurai strives for a world free of this kind of death, but will not abide unquenchable blood thirst, accepting that he damns himself by engaging in the fight.

Road House ends with a pretty killer final rout through Wesley’s garish mansion, where one knife in particular racks up an impressive body count. In the end Dalton tries to walk away from a defeated Wesley, no longer willing to stoop to the criminal’s level, leaving the various doughy businessmen of the town to do what they probably should have done all along with their many guns. Dalton then has a sexy(?) romp with his girlfriend in the river, a tidy and blissful ending. This is rarely the end for a samurai, and is certainly not where Usagi has been heading in Sakai’s work, where a few alternate timelines have carried nothing but further tragedy for the samurai rabbit.

This discrepancy doesn’t disqualify Road House from its samurai movie statues however. It gives me hope for Miyamoto Usagi, that his wandering may end with peace, the savage cycle broken, and an end to his foolishness. As Sensei Katsuichi said, Usagi should have gone home and lived happily as a simple farmer. Dalton did, so perhaps there is still a chance.

———

Levi Rubeck is a critic and poet currently living in the Boston area. Check his links at levirubeck.com.