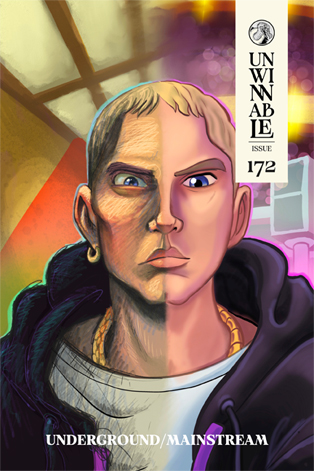

And the Crowd Goes Wild

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #172. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Interfacing in the millennium.

———

The first slice of narrative in Rollerdrome takes place in an empty locker room. Kara Hassan is the freshest meat in 2030’s favorite blood sport. She can poke around the possessions of her competitors, read notices intended for the athletes on the walls and check her messages at a wall-mounted computer terminal before heading into the rink, where she straps on a pair of roller skates and shoots the shit out of some people. Every time you enter a new set of levels in Rollerdrome you’re met with a similar snippet of story – Kara, alone in a room, poking through the detritus of others before skating into the arena to meet her fate. The act of wandering through these spaces where people used to be and aren’t proves to be oddly isolating, especially when Kara then leaves them to enter a place where she is the opposite of alone, where she is the focus of pointed, violent attention.

These peaceful establishing shots are an interesting choice for this kind of future blood sport. Rollerdrome‘s obvious inspirations (as cited by the development team) are Rollerball and The Running Man, classics of the genre, both of which allow few moments of quiet reflection for their protagonists. The closest similarity is Rollerball‘s Jonathan’s scenes of frustrated conversation outside of the context of the titular game, as he tries to decipher the machinations of his corporate owners that are pushing for his premature retirement; but of course, once he goes back to the rink, he has a team crowded around him and spectators right past the barriers, baying for blood. Kara has no team; her competitors, friendly and unfriendly, are never seen; her audience is far away, watching on a screen. The only other life in Rollerdrome is the House players who try to bring her down, and each one is masked and impersonal. Her only companions are an anonymous mass of focused violence.

Most future sport media establishes the violence of the sport as an approved outlet for societal pressure, a way for the general public to collectively release unsavory feelings and energy in a way that doesn’t upset the larger system in which they live. The existence of the sport within a larger society is key to its relevance – it wouldn’t be played without an audience. Screaming fans and crowds constantly tuning in heighten the spectacle, encourage more blood and exert psychological pressure on the athletes to meet their demands. In Rollerdrome, with these pressures only implied, not seen, Kara’s story becomes one of acute isolation. The game progresses, the difficulty curve grows steeper and Kara throws herself over and over into the meat grinder of swirling, ruthless sport for – for what? For glory? For money? For her own satisfaction, just to win, to have that feeling of it? There are revolutionaries who want to do something about the structure of their society that makes a game like Rollerdrome even possible, but Kara keeps her mouth shut about them enough to stay friendly for television – not like Lola Igwe, who is removed from the running early on for being too vocal about her support for the New Action Army, or Morgan Fray, the best to ever skate and shoot, whose ignominious death before the semifinals is a little too convenient to have come from fair play. Kept separate from her audience, the spectacle Kara creates echoes emptily – to what end, we don’t know.

The running theme between most of these future sports is that the players are both dangerous and in danger. In order for these games to work as an outlet of antisocial energy, they themselves have to be kept sanitized: the athletes are controlled, the score ends up where it should and the game never gets out of hand. The players’ fame protects them even as it reduces their agency, their personal freedom, and keeps them firmly in debt to the powers that be in their sport. The standard of violence in the various games serves as easy cover; their voluntary participation in blood sports absolves controlling interests of suspicion if something goes wrong. They take their lives in their hands every time they enter the arena. If a player is getting out of line – like Jonathan in Rollerball, whose longevity and high profile angered executives who wanted the game to reinforce the futility of individual action – the bloodletting gets sent in their direction. Jonathan’s teammates become the sacrificial lambs in Rollerball as the movie hurtles towards its nihilistic conclusion, every one of them wiped out so he can score one uncelebrated goal in a smoldering, blood-smeared rink, the howling crowd finally quiet, perhaps finally realizing what exactly they’d been cheering for. Rollerdrome couldn’t be more different. Kara has no teammates to protect her or avenge her; the arenas are quiet until the moment she enters and if she dies, she dies alone, under the watchful eyes of the House players and the camera.

It’s never quite established what Rollerdrome‘s sport is reflecting in the society that watches it. Are the general public kept sedate under the heavy hand of the corporate overlords? Do they watch because it’s how they can bare their teeth, how they can rebel without rebelling, feel something real and still go home at the end of the day? Or are the cities filthy and riotous like the gluttonous crowd in The Running Man, the game simply mirroring the everyday violence of dystopian life? All we know is their demand. Their willingness to watch and the International Rollerdrome Federation’s willingness to supply and Kara’s willingness to walk through those quiet hallways and throw herself, again and again, into the deadly fray.

———

Maddi Chilton is an internet artifact from St. Louis, Missouri. Follow her on Twitter @allpalaces.