1995

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #172. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Kcab ti nur.

———

“You may think we make a lot of money, but how much is a human life worth, demand comes and goes.”

There are movies where every drop of blood counts. Each drop has its own story, every person felled has a requiem. These are the opposite.

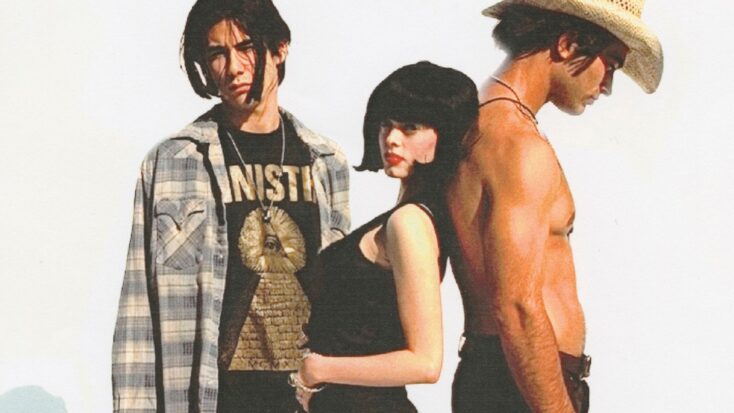

In The Doom Generation, the leading trio ends up covered in each other’s blood after the inciting incident that brings them together. While they wipe some of it off, there’s still a drop or a streak somewhere. As the death and violence mounts there is always fresh blood to replace it. Eventually, you just get used to there always being a drop or two of red clinging to something in the frame.

In Fallen Angels, our assassin is entirely detached from the lives he takes. Instead, he’s drifting thinking about his entanglement with his business partner and whether she’d make a good wife. We never learn any names of the dead, any reasons, we just know that he has been paid to kill them and so he does. For him, it’s just as mentally involved as flipping fast food burgers or color-coding a spreadsheet. In a different film, we’d see him quitting because the mental toll is too much, or worried because he’d had his family threatened, but Wong Kar-wai isn’t interested in creating a moral pretense for any of this. Instead, the hitman is just bored.

The detachment pulls through to how the violence is shot as well. Wong Kar-wai/Christopher Doyle are pulling on the slick camera techniques that Hong Kong cinema is known for while also playing intensely with frame rate, motion blur and harsh cuts. Distortion taken to 11 pushes us past cool suave action and into a chaotic blur that overwhelms you instead. Araki’s approach to violence, while a little less inspired by gritty crime thrillers, is no less frenetic. The sharp editing makes each act of violence feel like a frantic fever dream and before you even really register the death we’ve moved forward. The exception to this comes with the final act of violence, where the pacing and focus on faces force you to sit in the discomfort of it all.

Living in the lap of empire, it’s hard not to feel some of this detachment soak in. After all, we are shown violence done in our name on the screens that surround us every day. More specifically, as someone who lives in a rapidly gentrifying city, it feels like you wander through the ghosts of communities plucked apart by vultures. There is blood all around us – would we even know ourselves without it?

“There just is no place for us in the world.”

In both Fallen Angels and Doom Generation we follow dreamers. Wong’s Killer (Leon Lai) and Araki’s Jordan (James Duval) pontificate about something better being on the horizon. We see Lai’s look soften a little from the cultivated hardened exterior to wonder about what it would take to open up a bar. Duval’s boyish charm makes you buy into his melancholy entirely.

In Wong’s Hong Kong everyone’s hearts are so hungry, lost in the ever-shifting urban density. Desperate to find love, desperate to be remembered – even going so far as biting to make sure the mark is left somewhere, that there’s some record you existed at all. As with his other films, despite the packed proximity of the city, there is a constant feeling of distance between those inside.

By contrast, when Jordan dreams, he looks out into open vistas of California, full of color and possibility. It is particularly interesting to position Duval as the dreamer in comparison to his white counterparts. The colonial promise of California (and the American West) as a land of opportunity isn’t exclusive to white people, but the reality of what happens to those who try to cash in those promises is very different. And when we reach the conclusion of the film, he is well and truly punished for dreaming and existing in a space claimed by white America.

In the end those dreams don’t protect either of them from death. Jordan is murdered by the gang of his girlfriend’s Nazi ex, hellbent on revenge while covered in American regalia. The Killer’s dreams are ended after his now-former business partner puts a bounty on his head that the city is all too glad to take. Yet when they die the world doesn’t stop. It can’t, if all are doomed what’s another dead dream really worth?

“The road wasn’t that long, and I knew I’d be getting off soon. But at that moment I felt such warmth.”

Nobody in these films remains stationary long, whether rushing around the streets of Hong Kong or riding along the highway. Motion seems to be the only thing that keeps the doom away. I’m no good at stillness either.

What I appreciate about both these filmmakers is that there’s still value in the transitory moments. The desperate reaching means something. So does the brimming homoerotic desire in Arakii’s picture even when never completely fulfilled. The complicated love between He Zhiwu (Takeshi Kaneshiro) and his father (played by Man-Lei Chain) is not made worthless by the indirectness of their expression or the fleeting nature of their interactions. The warmth and bonds found, however messy and unconventional and temporary, still have weight.

Both Fallen Angels and The Doom Generation end with characters riding on into the proverbial sunset, they keep moving long after the film reel runs out. I don’t know whether to be encouraged or depressed by this. It’s been nearly thirty years, and it still feels like we’re doomed. Maybe it’s the fate of each generation to feel uniquely doomed, or maybe things have just never gotten any better. But hey, maybe we can just keep riding until we hit something that half resembles a future.

———

Oluwatayo Adewole is a writer, critic and performer. You can find her Twitter ramblings @naijaprince21, his poetry @tayowrites on Instagram and their performances across London.