The Surprising Horrors of Frictionless Romance

When I first played Baldur’s Gate 3, Shadowheart’s romance struck me as a horror story – and not in the way people familiar with her arc might expect. While one of the only things I knew about her – and she knew about herself – was her lifelong ambition to become a Dark Justiciar, a kind of enforcer priestess for the goddess she worshiped, she suggested unprompted that maybe it didn’t matter anymore. Maybe all she needed was me.

While being an enforcer priestess for an evil goddess isn’t the healthiest career ambition, it’s a more solid foundation for an identity than being someone’s girlfriend and nothing else, and I flinched at her apparent willingness to surrender her autonomy. But of course: Shadowheart isn’t real, and as a fictional character she has no autonomy. Instead, her actions are compromised between what satisfies her arc – and what rewards player interactions.

The conflict I’d come across here is that romances in RPGs like this are framed around giving the player what they want – and the player’s interests are incredibly broadly defined. Romance options aren’t designed with the tools to be discerning. Regardless of appearance, sense of humor, or whether or not the player is a morning person, they’ll be devoted so long as an approval threshold is met.

This isn’t just about Shadowheart, of course. At Kotaku, Kenneth Shepard spoke to games writers across popular RPGs and dating sims about “playersexuality”. In games like Boyfriend Dungeon and Baldur’s Gate 3, where the romance options are all either implicitly or explicitly pansexual, they approach the player without regard for their gender at all.

This gives the player more freedom – but it doesn’t ring true to life, as even people without a gender preference can still find it impacts the dynamics of how they date and flirt. In contrast, story arcs like Dragon Age: Inquisition’s Dorian’s relationship with his father are only possible because he is specifically a gay man – but it puts the player in the undesirable position of being able to be rejected for a romance without them doing anything “wrong”.

If I want to enjoy romances in RPGs, it seems against my best interests to want more friction in them – to want it to be more likely for characters to reject me, or prioritize their own causes. And yet, when I want to romance a character it’s because I enjoy the character, and I want to see them go through their most interesting arc.

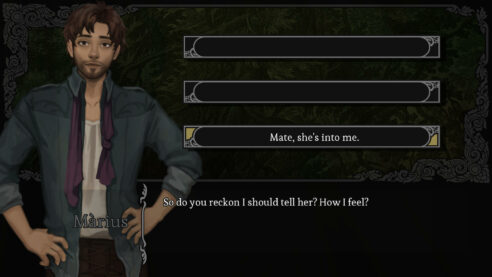

Maybe this is why last year I was so taken by Amarantus, a visual novel with the kind of scope to let its characters respond in very specific ways. With its fixed main character and set histories between its cast, there’s no sense of conflict between a character’s arc and their availability to be romanced. Instead, when I express my interest in the messy, impulsive Màrius in an attempt to dissuade him from kicking up an ill-advised fling with someone else, it doesn’t work – it just tangles us both in the complicated situation his arc was always unfolding into.

There’s a “shorter games with worse graphics” maxim in there somewhere – fewer freedoms for less romance – but what I really mean to come to is that when a romance option feels too compromised by its ease of access, it can make the character feel more like an object than a person. And when the framing rapidly switches from person to object, it can feel far more like a horror story than a romance.

———

Ruth Cassidy is a writer and self-described velcro cyborg. They can be found in various places at linktr.ee/ruthvcassidy.