Games with Teeth

When I’m deep in the dungeons of Fear and Hunger 2: Termina, my party sick and limping, dark shapes swirling and converging in the shadows, I feel a special brand of misery. It’s been hours since my last save point, I’m out of rations, and multiple characters are stringing along with single-digit hit points. My doom waits around the corner with the patience of a trained killer. I think wistfully of the hours preceding this moment, how trivial and simple their challenges were in comparison. It’s dark. I’m in the mouth of a beast, and its teeth are razor sharp.

This is the pivotal Termina experience – to be in some form of distress, and for that feeling to heighten each moment of both triumphant success and tragic failure, along with every harried battle and blasted beast in between. And though the hooks of its teeth are undeniably keen, the scars they leave on my battered fingers are worth the painful price of admission. While much of mainstream gaming is afraid to engage with difficulty, Termina understands that some aesthetics can only be experienced when a game is bold enough to be cruel.

Games, and those who play them, often assess difficulty as some external organ from the rest of the body – a necessary yet separate function acting as nothing more than a slider to alter the relationship between player and game. Should my experience have friction? Should combat require me to use the full suite of available tools, or let me slide along with only surface-level understanding? How can this game be stitched and tailored to fit my body like a tight suit? Not the beating heart, but the frayed clothing that surrounds it. Despite its initial promise of flexibility, this perspective is inherently limiting because it only allows a game to be what the player can comfortably tolerate. An RPG that changes its shape in order to appeal to any audience runs the risk of appealing to nobody in the process. This is evident in titles like Fallout 4, which traded its predecessors challenging tactical combat and generous roleplaying opportunities for approachably bland FPS shootouts and quests that can’t be failed. It filed down the sharpest points of Fallout’s talons, and as a result its grip leaves no mark on the player’s wrist. If a game wants to truly linger in the mind of its audience, it must have moments that descend from slick fantasy into waking nightmare.

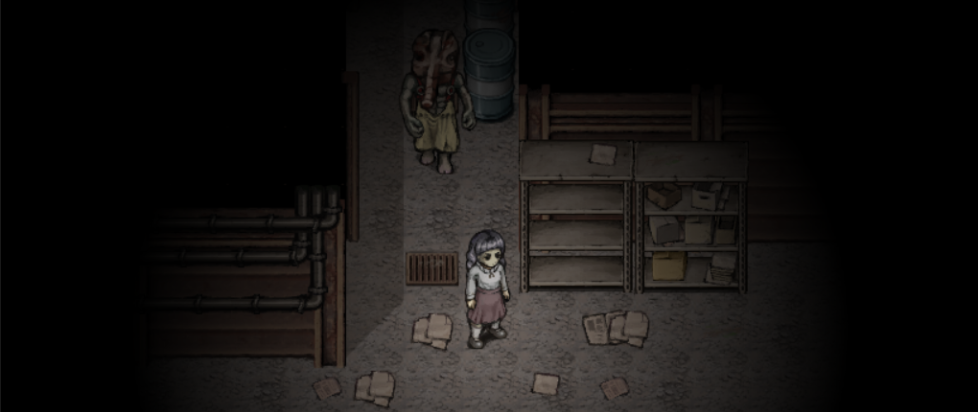

There are a handful of moments throughout Termina when the player’s party must venture into a hellish reflection of reality – a world covered in split wooden boards that teeter over a dark void, where bloody demons that speak abomination incarnate roam in search of fresh meat. These sections of the game are, frankly, miserable. Enemies are overwhelming in both their numbers and individual strength, and instant deaths are all-too-common, compounded by the brutal lack of nearby checkpoints. My gut flooded with dread upon entering these thresholds, and I never enjoyed the experience of slowly conquering them.

Yet conquer them I did, run after run, the corpses of each death piling ever-higher in that dark swelling ink under the floorboards. Being butchered by invincible enemies was not fair, perishing from hard-to-spot traps was not kind, but I memorized their harsh lessons all the same. I continued to push forward and die faster, walking the same split boards with a deft grace. I painstakingly prepared for each enemy encounter as though it was my last and walked into every room with the learned caution of a once-captured animal.

Incredibly, inevitably, I would endure to the end. My party would emerge from the dungeons’ dark recesses and be welcomed with food and a much-needed save point. Regardless of this fruit’s rotten nature, its layers peeled back soft and agreeably all the same, and at its center a fleshy pulp was revealed, that undeniable feeling of overcoming odds so insurmountable that their defile borders on the surreal. The game had scraped and wounded and bled, and finally I got to take a bite in return, its taste so sweet and sharp that tears were brought to my eyes. It was during these moments that Termina’s senseless cruelty began to make sense – the success of my party delivering a pang of sincere emotional catharsis amidst the countless bones of their past obliterations.

It’s important to note that this intense, apathetic difficulty works because of two things: a thematically matched setting, and the powerful allure of discovery. It would feel wrong to navigate the apocalyptic town of Termina, reeking of boiled guts and unrestrained corruption, without the constant hunting pressure of death. When I am afraid and tired and desperate to find a save point, I am merely echoing the state of the characters in my party. We may be miserable, but at least we are miserable together, abiding by ludonarrative coherence in the process. This coherence creates a specific kind of inward-facing frustration – when my party dies, I am distraught for their sake rather than my own, increasingly fascinated at the endless brutality of the world they explore. And what an explorable world it is! Termina is all dead ends and twisting tunnels, powerful secret items hidden behind obscure corners of abandoned labyrinths, a great sprawling mess of trenches and traps that boast danger while simultaneously hinting at great opportunity. Players are let loose in this environment like a rat in a maze, free to explore and learn and die at their own pace, and this freedom mitigates much of the frustration after failure. The sting of decapitation via axe-wielding madmen may be sharp, but its pain is remedied by the knowledge that I discovered a brand new area or gnarly weapon prior to my untimely slaughter.

There is an inherent satisfaction in playing a game that hates you, as it becomes not just a game but a desperate fight between artist and audience, something impossibly frightening and infuriating and exulting. I led my party through death and despair and broken bones, into dungeons so deep and so dark I was convinced we would never again taste the sunlight, and yet each time we emerged victorious. Eventually we escaped those dark pits for the final time, missing limbs and all, welcomed home with warmth and full bellies. My fingers riddled with the scars of hard-earned lessons and my mouth tasting of succulent fruit, I completed Termina with the new understanding that difficulty does not have to be the arbitrary external organ – it can be teeth, it can be sharp claws and a hungry mouth, it can be eaten and it can be sweet. Through its uncompromising viciousness, Fear and Hunger 2: Termina displays the powerful role that difficulty can fulfill when games stop conforming and start biting.

———

Hayes is studying game design and technical art at the University of Utah. You can find more of his ramblings here.