Now You’re Playing with Privilege

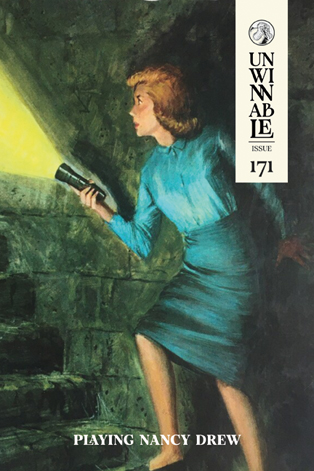

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #171. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Analyzing the digital and analog feedback loop.

———

When I sit down to play games lately, I’m aware of the paradox of experiencing an interactive, on-screen representation of agency whilst being idle and at my leisure (whenever I manage to have any). With times being as turbulent as they are in real life, sitting and appreciating a game’s artistry feels distinctly useless at times. There’s also a sense of guilt from seeking escapism, despite knowing that in order for me to balance my mental and physical health I need to have temporary moments of reprieve. Keza Macdonald made a keen assertion in recent years about how games are often reduced to objects of paranoia for society, when in fact they can of course be beneficial to our mental health. I believe wholeheartedly as well in playing more when you’re down, as per the definition of “sad games” that Johnny Chiodini coined several years ago in his “Low Batteries” video essay series. After all, I cannot offer those in need my endurance if I have none left to operate with. And of course, there’s nothing inherently bad about escapism or nostalgia – it’s about how we choose to indulge in either that’s key.

What I struggle with most with regard to videogames as an art form recently is that it’s a medium that centers agency, yet often only a privileged kind of agency. It’s the agency of someone who’s almost always in a position of power, although I’m happy to say that there are more games being released that center community narratives now than ever before. And games are slowly becoming more diverse in their representation as well. I’ve learned a lot from the philosophy of some of these games, especially indie titles like The Archipelago, Venba or Solace State.

Empowerment can be about more than privilege, of course. It can be about collective action towards an issue that those in authoritative positions of society are exacerbating or ignoring. This dynamic has been made increasingly more apparent in both games theory and narratives about gaming culture, like Javy Gwaltney’s excellent story collection Into the Doomed World. Empowerment can be about using one’s silence to amplify the voices of the marginalized, a transfer of privilege if you will. Empowerment can be about teaching people that they deserve to be autonomous and that consent is non-negotiable when it comes to situations that jeopardize your autonomy, bodily or otherwise. Empowerment can be about accepting that death is a part of life, as the rise in death-positive games in recent years posits.

Another facet to the tug-of-war my mind has been the idea that there are many who feel it is an attack for people to discuss the hesitancy to engage with escapism. I get it. Games are still a relatively young and often contested art form. They may have become a lot more a part of our everyday grammar, both figuratively and literally, but they’re still something associated strongly with wasting time. But “wasting time” is such a constructed and capitalist notion. Playing games, whether at the AAA, AA or indie level, reminds us powerfully that it’s okay to indulge in your inner worlds and that humans can just be.

I know it’s rather inevitable for me to turn to this subject, as a game critic and a hobbyist game designer. Anything that flies in the face of the hustle can potentially cause me guilt. Many people of the Western world like me have been indoctrinated from an early age with bootstrapping philosophy. As Tricia Hersey of The Nap Ministry asserts, rest truly is resistance, especially for the marginalized who have been positioned as lazy or unprincipled despite often needing to work three times as hard to remain stable. If they are even able to, that is. The toxicity of ableism is something that’s often ignored in grind culture or even celebrated instead as a worthy trait.

Kara Stone, one of the game developers and scholars I admire the most, once gave a short talk on mental illness and making games for a GDC 2019 indie panel. She is known in recent years for her titles Ritual of the Moon, the earth is a better person than me (a.k.a. Earth Person), UnearthU and is currently working on a solar-powered web server project. The latest is premised on developing low-carbon footprint games whose development cycles and play time is deliberately slowed down to a more organic and therefore unpredictable pace. Her GDC talk, despite already being half a decade old, is no less relevant to those in and adjacent to the games industry. Stone’s philosophy regarding overwork or “crunch” in game development is that “productivity isn’t worth the debilitation” and the process is worse for those suffering from mental illnesses or disabilities (visible or invisible).

Gracefully dovetailing with this philosophy is her statement regarding the unpredictability of access to her solar-server project, given to Guardian interviewer Lewis Gordon: “Not everything has to be accessible to everybody at every single moment . . . Full access to every user is such a capitalist mindset.” Her mention of persistent access as capitalistic entitlement strikes me, as I believe this is the underlying sentiment of what drives my guilt when I sit and binge an open-world escapist buffet like Baldur’s Gate III. In Stone’s GDC talk she also points out that a lot of games are modeled after capitalist notions of agency and progress. Endless checklists of goals, achievement trophies for said goals, tiered and often prejudiced experiences via difficulty levels, etc. I half remember a social media chat on the platform formerly known as Twitter, in which a game developer said only half-jokingly that the subtext of every narrative-driven game is the story of struggling as part of a game development team. Perhaps that sheer exhaustion bleeds through the narrative design and its attendant mechanics.

Escapism and nostalgia are not inherently ignorant or irresponsible, but I think there’s something to be said about resisting criticism about the rosier elements of games too. When we’ve never been more aware that collective action is necessary for change, even within the medium we love to engage with, there’s such a railing against labeling games as anything other than revolutionary. But games cannot truly be called such if the people making them are treated the way they are in the development of them.

No Escape and others have been tracking the devastating layoffs that have been happening throughout the industry and adjacent industries like games journalism have been impacted too. But people don’t want to hear anything about the downside of games development. They also don’t want to be told that their current favorite titles (whether AAA or indie) are made often at the detriment of other people’s health and well-being. This well-researched and insightful piece, however, has drawn ire for simply stating the facts. Our escapist, agency-centric art experiences are often delivered to us at the cost of other people’s agency.

C.Thi Nguyen, a game studies scholar, believes that the strength of games as an art expression is this ability for game designers to offer us alternate forms of agency to submerge ourselves in. Nguyen claims that unlike practical everyday life and its social constructs determining our perspective as looking forward and justifying our goals and our means for reaching them, games invert this state of affairs. We are encouraged in games to look backwards at our process of overcoming obstacles and getting intimate with our means of reaching our goals. “[We] can take up an end for the sake of the means”, Nguyen explains. I agree with this argument, but would add a caveat: only those who are privileged enough to access these alternate forms of agency. Whether that is financial access, physical access or cognitive access, etc. I do not mean to say that all games are experiences of arch privilege. But we are only just starting to scratch the surface of improving the interface of games and the market of games so that more people can experience this unique way of designing and expressing alternate agencies.

A lot of this has been knocking around my head because The Discourse™ is circular, like my ruminations, and the end of the year is often when I need to name things to tame them. Hopefully my venting isn’t too selfish or performative in that regard. Feel free to call me out on this, though politely and constructively I should add; don’t punch down on my neurodivergent brain, please. I’d like to return briefly to Keza Macdonald once more, as she continues (along with other veterans in games journalism) to drop wisdom this past year.

![Screenshot of a tweet from Keza MacDonald reading: “The chief reason that video games criticism seems to have no memory – why we see the same discourses repeating eternally with no sense of the vital context of what went before – is because games crit is so poorly respected and remunerated that people rarely last longer than 5 [years].”](https://unwinnable.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/10-Interlinked-1.png)

There’s a quote-tweet (Post? Whatever.) of hers that struck me upon reading it. Macdonald commented on Gita Jackson’s recent criticism of the interview with J. Robert Lennon and Carmen Maria Machado about their game criticism anthology that presents itself as the first of its kind, explaining that “The chief reason that video games criticism seems to have no memory – why we see the same discourses repeating eternally with no sense of the vital context of what went before – is because games crit is so poorly respected and remunerated that people rarely last longer than 5 [years].” One only has to look at the current state of layoffs in games journalism/criticism due to AI technology and the gig economy grind to see that this tracks.

We need to analyze how our bodies are performing agency within and outside of the magic circle of a game. As well, as we move forward, we need to be keenly observant of whether we are allowed within that magic circle to immerse ourselves in alternate agencies in the first place. We talk of immersion constantly in games, but what if we applied that principle to our everyday existences? I’m not saying we “lean in” per say, as that’s not possible for each and every one of us to do. There are many roads to revolution, as they say (usually they in this instance are trustworthy or at least earnest, “they” signifying those resistant to oppression). Perhaps at least partially because it reveals the lie baked into the constructed social narrative that creates and divides “us” from “them.”

———

Phoenix Simms is a writer and indie narrative designer from Atlantic Canada. You can lure her out of hibernation during the winter with rare McKillip novels, Japanese stationery goods, and ornate cupcakes.