Death is Not the End: How to Win and Die Trying in Doomseeker

I see board games in the store and they always look so cool and then I buy them and bring them home, I’m so excited to open them, and then I play them, like, twice… This column is dedicated to the love of games for those of us whose eyes may be bigger than our stomachs when it comes to playing, and the joy that we can all take from games, even if we don’t play them very often.

———

It will come as no surprise to anyone who has spent any meaningful time reading this column that I am relatively immersed in the various worlds of Warhammer, as published by Games Workshop. This relationship goes back to small times, and I was introduced to Warhammer before I had ever played a single game of Dungeons & Dragons.

So, for anyone whose background is different from my own, the only way to explain Doomseeker – a card game from Games Workshop by way of Ninja Division – is to first explain the concept of a dwarven slayer.

In the fantastical setting of the original Warhammer fantasy games (now called “Oldhammer” by those in the scene), a dwarf who feels, for whatever reason, that they have dishonored themselves or their clan, may choose to take the Slayer’s Oath. When they do this, they shave their hair into giant, fiery orange mohawks and venture out to find the biggest, toughest, meanest monster they can and die fighting it – thereby recovering their honor in death.

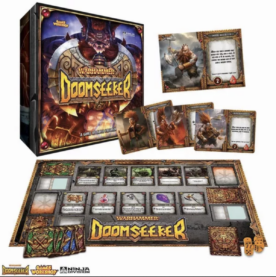

In Doomseeker, you take on the role of one of these slayers. Your goal is to die in glorious combat. To get there, you start out fairly puny, armed with nothing but a hand of fate cards that can potentially put a thumb on the scales of destiny. You deal out a hand of monsters to fight and then you go to town. Every turn you’ll pick a monster (called a “doom”) to pit yourself against. Then all the other players get to play fate cards to make it harder, or easier, or pick a different doom and let you know that you’re fighting that one now, or step in and fight the doom themselves instead.

Which means that how things are going to play out when you make your call and how they actually play out when it comes back around to you may be… very different. So, why try to win at all if you’re after a glorious death? The key is that “glorious” part. No one ever redeemed their honor by dying in combat with a bunch of weedy little goblins. You want to go out in a blaze of glory against the toughest monster in the deck, and that means wading through a bunch of littler ones first.

To do that, you have to pick up gear from the item shop, which you buy with the gold you get by slaying monsters. The gear involves a bunch of standard fantasy loot, including healing potions and a mug of Bugman’s brew (familiar to any seasoned Warhammer player) that will give you a jolt of added strength.

It also includes a lot of axes. And I mean a lot. And since cards can (and, indeed, must, if you want to get the job done) stack, you’ll likely be wielding a lot of axes. At once. Like, four or five. We figure you just grab one between each knuckle, like Liam Neeson with those broken bottles in The Grey.

Here’s the thing, though: This is a game where it actually does pay to die, if you can do it when you mean to. The points in the game are scored by collecting renown from the dooms you take out. But the doom that kills you counts, too, and if you get knocked out by something big and bad enough, you score extra.

What’s more, there’s an additional mechanic that only comes into play if you die. The first few times I played Doomseeker, I was playing with only two players. Like a great many games of its type, Doomseeker technically can be played with only two players, but it is a very different game with more. This is because of the fate card mechanic I already mentioned.

With only two players, the other player plays a fate card, and then you do. They have a chance to change the level of the playing field, but it’s not as likely to alter completely as it is when there are four players all playing fate cards one after another. In one game that we played, a particular battle changed hands twice before anyone got to fight, with two different players stepping in and saying, “Nope, actually, I’m fighting this one.”

When a slayer perishes, there’s also a mechanic that comes into play with multiple players that doesn’t really have any effect when there are only two. When your slayer meets their final (hopefully glorious) doom, they may be out of the game, but you’re not. You can keep playing fate cards every round, though you don’t keep drawing them as much, so you may run out unless you play them strategically.

Perhaps more importantly, however, you can also bet on the outcome of the fights that haven’t yet happened, provided you have the resources to do so. These bets can earn you additional renown, which translates to a higher score and a chance of winning the game, even if you were the first one to go out in a blaze of glory.

In fact, in one of the games we played, one player racked up more posthumous points than the second-highest scoring player got total. The deceased player’s ability to continue throwing monkey wrenches into the gears of fate from beyond the grave can also be potentially game-changing, deciding who wins and loses in the desperate final rounds, as the biggest and scariest monsters hit the board and everyone is throwing everything they’ve got into a last, doomed battle.

It’s a fun, unpredictable game that veers from camaraderie to cutthroat with little warning, where the best-laid plans of doom-seeking dwarves can be undone by the random – or spiteful – turn of a card, and where helping another player win may often be as beneficial to you as making sure that they lose, depending on the turn.

———

Orrin Grey is a writer, editor, game designer, and amateur film scholar who loves to write about monsters, movies, and monster movies. He’s the author of several spooky books, including How to See Ghosts & Other Figments. You can find him online at orringrey.com.