Bloodborne’s Fresh Insight on Cosmic Horror

The tropes in H.P. Lovecraft’s work have been adapted and transcribed so concretely that “Lovecraftian Horror” is a synonym for the name of the wider thematic genre they spawned: “Cosmic Horror”, which depicts humanity as infinitesimal beings in the broader world and ruminates on the dread of this knowledge. As Lovecraft himself says in the opening to “The Call of Cthulhu”: “We live on a placid island in a sea of ignorance…”. Every step towards discovery and investigation – both historical and scientific – pushes mankind deeper into the realms of forbidden knowledge.

These themes (and Lovecraft’s often grotesque, incomprehensible monsters) have made his works a prime source of inspiration for videogames, both in the genre of horror and beyond. Games such as Frogwares’ The Sinking City and Cyanide’s Call of Cthulhu are almost direct adaptations of Lovecraft’s work, even if the protagonists and actual settings are wholly reimagined. These games, which focus on investigators uncovering secrets and monsters in Innsmouth-esque towns, transcribe “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” and “Cthulhu” faithfully. And this is part of their problem. With their overt grounding in Lovecraftian towns, the initial mystery that leads to the discovery of dead and dreaming gods is preemptively spoiled. Both are entertaining games, but their narratives fail to embody the dread and slow creep towards madness that define cosmic horror.

FromSoftware’s seminal 2015 game Bloodborne is not horror by its conventional definition, instead a crimson-soaked hack-and-slash with a Victorian aesthetic, but Bloodborne’s narrative and gameplay progression are indirectly adapting the most effective aspects of the Lovecraftian weird tale. The beginning of Lovecraft’s stories are often quaint in this way – men of stature, academia or both uncover an oddity that necessitates further investigation. These protagonists, mostly men, blindly travel into townships or cities unaware of their terrifying depths. For example, “The Call of Cthulhu” opens with an antiquarian investigating an unusual carving of the titular god, rather than showing the machinations of the creature itself. Lovecraft often marinates on the oddities of his worlds, peeling back the masks of his beasts only when their influence can be the most maddening.

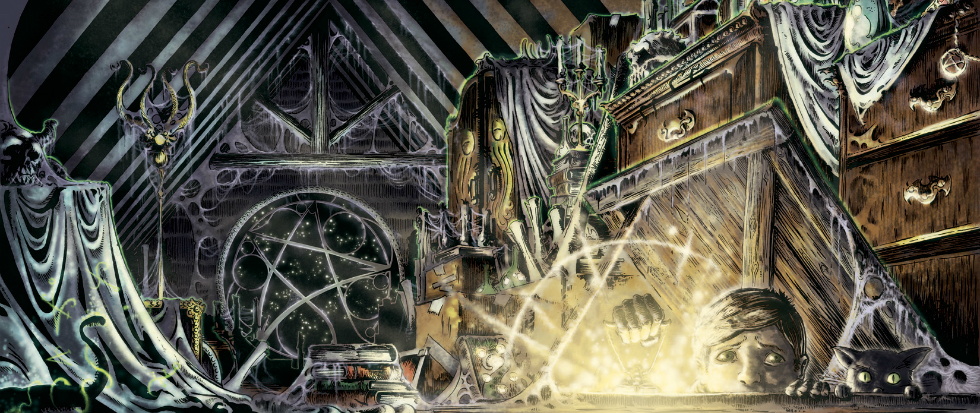

The first hours of Bloodborne are bathed in Victorian Gothic architecture: The player fights large, werewolf-like beasts and men driven to madness by the taint within their blood. Tall churches and buildings are off in the distance, and the player, who has been sent to the town of Yharnam by some sort of supernatural blood transfusion, is left on their own to find a way out. The game slightly betrays its shifting aesthetic with the “Insight” meter that ticks up when a player encounters a new boss or activates a “madman’s knowledge,” but the effects of this status are so subtle as to seem meaningless to a new player. The fact that the player can exchange these points for special items serves to justify them as a mere secondary currency.

Then, halfway through the game, after exploring a city of beasts and a forest full of madmen and serpents, the player navigates the lost ruins of Byrgenwerth to a balcony overlooking a lake. They dive into the moon’s reflection, are brought to a white dimension beneath the water, and, perhaps unknowingly, they kill a god.

The death of Rom the Vacuous Spider breaks the masquerade. The moon turns blood red, and a woman in a dress, who seems to have miscarried, haunts the white realm. The distant sound of a baby wailing gives the player their next objective: to slay one more dead and dreaming god.

The player can locate this door before this segment, but they will be unable to open it; unless they are very specifically hoarding their insight, they will also be unable to see the large, lotus-headed amygdala looming over it.

As the player descends into the hidden city of Yahar’gul, a droning soundtrack of religious chanting behind them, they also uncover monsters composed of piles of flesh, and fight an assembly of the dead. It is only then that they are able to enter the Nightmare of Mensis to finish the game. All at once, the Victorian aesthetic of Yharnam is corrupted, brought closer and closer to true madness. The player’s sanity begins to fragment; an oft-loathed enemy known as a Winter Lantern, a corrupted facsimile of the Hunter’s only true ally, is capable of driving the player to instant death just from the sight of it. Spikes of concentrated madness stab at the player as they hike the Nightmare.

The Hunter is, more than anything, a stranger in a strange land that slowly shows its true colors. Unlike The Sinking City or Call of Cthulhu, which hint at the cosmic nature of its antagonists from the start via their overt inspirations, Bloodborne forces the player into the role of Lovecraft’s damned investigator. It is no mistake that Bloodborne only presents a fishing hamlet as the final area of its DLC, at which point the cosmic horror should be all but obvious.

To complete the game, the player has to kill two cosmic beings at minimum, but there are far more secrets sealed away. Through a broken window in the Upper Cathedral Ward, an area that is entirely optional, the player finds an elevator that leads deep beneath the Cathedral to an altar, where Ebrietas, Daughter of the Cosmos rests. Finding three Umbilical Cords and consuming them grants the player enough insight to find a secret final boss: the Moon Presence, the architect of Yharnam’s nightmare. If the player navigates through the Fishing Hamlet in the DLC, the player may find the screaming, newly-born Orphan of Kos (or some say Kosm) and slay it.

Each discovery that pulls the Hunter (and by extension, the player) deeper into the cosmology of Yharnam is paced such that the broader details remain beyond the veil until it is far too late to stop them. The player does not know what illusion Rom upholds on a first play through. Their attempts to gain understanding and to navigate the challenges of the game only serve to unleash greater and greater scions of madness, until at last the player is able to escape them (though changed forever), become enslaved, or ascends into a Great One themselves. In a 1927 essay entitled “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” Lovecraft states: ”The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.” Bloodborne’s shift from Gothic Horror into true Cosmic Horror keeps the player on the precipice of unknowing, and in emboldening them to investigate further, only drives them towards horrid truth beyond our understanding.

———

Joshua M. Henson has been playing video games since Doom II at the age of four, and hasn’t shut up about them since. You can find him on twitter posting very occasionally.