It’s an Evil Effing Room: Level Design in Horror

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #170. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

We are what we’re afraid of.

———

In Mark Z. Danielewski’s book House of Leaves, alongside constructing one of the most unsettling haunted houses I have ever had the pleasure of encountering, also introduced me to a philosophical horror concept that reframed the way I think about a lot of my spookier experiences. In the book, Danielewski muses at length on Heidegger’s concept of the unheimlich, literally translated from the German as “un-home-like.” While I personally tend to balk at working with Heideggerian concepts myself, since in his life he had many unpleasant associations with the Nazi party and I want to be entirely transparent about that, he’s also really hard to get away from if you do any sort of work with western philosophy, literature or criticism. And this idea of the un-home-like or unheimlich has stuck with me because I feel like it presents a very particular phenomenon in regards to the way we experience the discomfort of horror, similar to but distinct from things like the uncanny valley. A horror of place and of environment, as opposed to horror distilled into discomfort at a specific object or person. Horror at the level of vibe.

On a broader scale, our media has a bit of a fascination with the idea of place-as-evil. Haunted house horror has been present since horror media was a thing (here’s looking at you, Edgar Allan Poe), and we’ve seen basically every titan of the horror industry take on the concept, from Shirley Jackson and The Haunting of Hill House to Stephen King himself in, among other properties, 1408, the film adaptation of which inspired the title of this piece. I’ve actually written about my feelings on the unheimlich previously, in the now defunct We Are Horror, may that publication rest in peace. But I think the specific ways in which videogames handle place-based horror deserves its own moment to shine, because in thinking about horror level design, we can work to uncover a lot of the general horror philosophy behind some of our most beloved franchises.

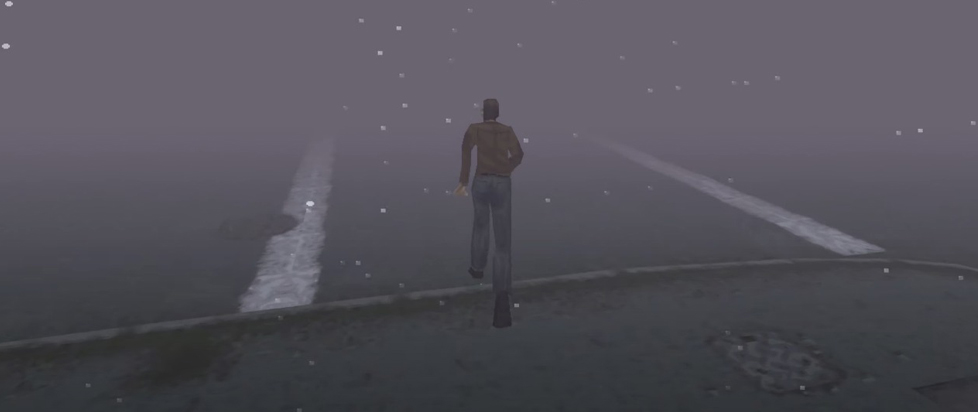

While in a typical study of level design, it would seem that the things that are present (objects, platforms, interactables, etc) would take center-stage, in horror level design, negative space and things notably absent are equally important to creating a sense of the unheimlich. For example, one of the most iconic level designs of all time is the exterior town in the original Silent Hill, which, due to technological constraints, had incredibly low visibility thanks to the dense fog shrouding the player character. While this design was born out of necessity, its impact on the terror of traversing the main map is unmistakable: the only indication that danger is in the vicinity comes from the tinny blare of your radio. Since the level actively obscures any visual notice of danger, the player is awash in a literal sea of the unheimlich. Things here are out of sight but very much not of mind, and there is no reasonable assumption that what’s on the other side of the fog is normal, pleasant or safe.

Silent Hill 4 more directly engages with the idea of the unheimlich, since the premise of the game (which, as a side note, I contend to be the most thematically interesting in the series) is that you are trapped inside your one bedroom apartment and can only escape through increasingly threatening holes that appear in your walls. Through these holes, you as the protagonist escape into surreal locales that on the best day would seem like liminal spaces, such as an empty subway station. These sojourns are limited, however, and you inexorably return to your apartment, slowly and horrifically changing with each new outing until finally, the apartment actively damages your health for as long as you remain inside. The home, traditionally thought of as a safe haven, is here turned on its head, and you are forced to flee that which is meant to protect you.

This really only scratches the surface of the examples for horrors of place in videogames, but what does all of this mean? And why is this significantly different in an interactive medium than in a passive one like film? Fundamentally, the difference here lies in the fact that, in a film about a messed-up place, the rules about how to watch a movie remain unchanged, whereas in a game about a messed-up place, we have to totally reconfigure how we interface with the medium. The very rules of play change when we can’t trust, for example, that a wall is a wall, or that it’s safe to exist inside of a given area. And it’s for this reason that place-based horror tends to be some of the most viscerally unsettling to us – it takes the ground from beneath our very feet, and we are left unanchored, strangers in a strange land.

———

Emma Kostopolus loves all things that go bump in the night. When not playing scary games, you can find her in the kitchen, scientifically perfecting the recipe for fudge brownies. She has an Instagram where she logs the food and art she makes, along with her many cats.