The Tunnel to Summer, the Exit of Goodbyes

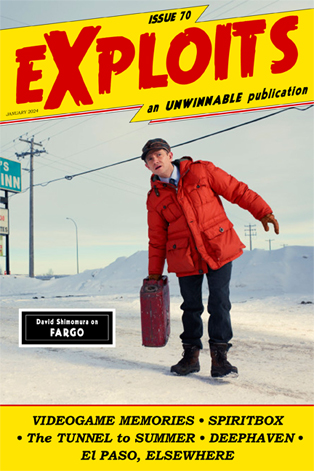

This is a reprint of the Movies essay from Issue #70 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

This is a reprint of the Movies essay from Issue #70 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

———

I guess the worst things about The Tunnel to Summer, the Exit of Goodbyes aren’t director Tomohisa Taguchi’s or studio CLAPSs fault. Its story, inherited from Mei Hachimoku’s light novel of the same name, is an excess of sekaikei tropes. Critics and academics (and myself) have written about the “world type” genre, characterized by its juxtaposition of apocalyptic crisis with school romance. Formally, its protagonist (always a boy) is disempowered from actually confronting the crises around him while his love interest, some take on a school girl with a mech or magical powers, fights to save the world and resolve his conflicts while he never really has to grow, develop or do anything besides wallow about how awful the world around him is.

While The Tunnel to Summer, the Exit of Goodbyes is a coming-of-age drama without any action – all its conflict is psychological – it still invokes all these tropes. Protagonist Kaoru is a highschooler in a small town living with a shitty father and grieving for his dead little sister. Then he encounters a new classmate, Anzu, in a manic pixie dream girl-ass meet cute. We find out much later Anzu left her family and lives on her own as a high school student to pursue her dream of becoming a mangaka like her grandfather.

They’re both pulled to a tunnel in the woods near where they met. A twist on the fairytale of Urashima Tarō, the tunnel seems to promise them their dead family . . . or something. Together they spend after school and weekends investigating the tunnel and learning its magical rules – namely that time passes much, much faster inside. Venturing far enough inside to find out what, exactly, they seek would mean losing decades to the real world.

So, after making an elaborate plan to both run away into the tunnel together, Anzu gets an offer from an editor and Kaoru decides she should pursue her dream in the real world while he fucks off into the tunnel without her.

Anzu grows up, gets published, makes a career, and (as mangaka do) becomes jaded and burnt out. She faces the real world and grows up, but she still carries around her old flip phone waiting for a text from Kaoru inside the tunnel. Meanwhile Kaoru spends a few hours in the tunnel, meets an illusion of his baby sister who is able to bestow upon him the most basic morals of the story, and he decides to return. When Kaoru emerges he’s still a teenager, but all the wiser because his dead sister told him how to feel

Narrative contrivances of fate bring the two back to the entrance of the tunnel after Anzu has aged eight years. Like every woman I know, she’s still in love with her high school crush who is literally a child now and they kiss. That’s the happy ending. Beyond how mind bogglingly devoted this plot is to the idea of true love or how it seems to forget the bitter ending of the fisherman’s fable, it’s all the more infuriating to watch because he literally does not grow up! The age difference should emphasize Kaoru’s flaws, but instead this is considered resolution somehow. Stop kissing children!!!