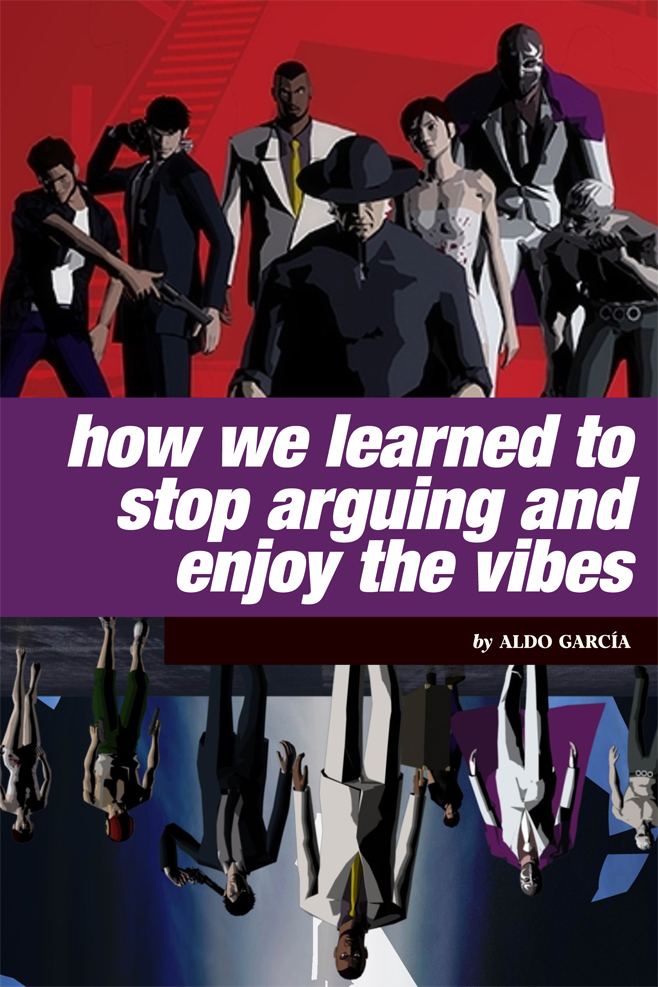

How We Learned to Stop Arguing and Enjoy the Vibes

This is a feature excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly #170. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Subversion (like most things regarding modern politics) is a disagreement. An objection, seeking to make a contradiction visible – like following a dot to call attention to other various dots and threads until a chain of connections presents itself (ideas, circumstances, relationships, agendas) – and a frame is revealed. For a course of action to follow suit, then, strong impressions (power) are displayed; to distance oneself from the frame; to implicate us all. To send, in other words, a direct request (invitation).

Aesthetics, however (like most things regarding modern politics), is an impression; sensations being invoked for a particular effect. When done in excess or without a clear political intention in mind, the opposite is true; the frame and the impression become muddled (taken advantage of) – like hyper-fixating on the picture within, to the point of overlaying a new personal (intended) outline on top of the original. Perception, more than an instrument for collective action, becomes a compromise; it creates new meaning outside the intended one. It makes any frame, you see, into whatever you (they) want it to be.

To the dissident agent, it’s a blatant invention, and it denounces it as such; to some within this frame, however, this looks (feels) subversive, like the start of a conversation they’ve only had with themselves; and now, constrained by its captors, fueled by their “rejection,” hungry for a frame that keeps upholding them, one must only ask the question they’ve always longed to hear:

“What would you do to keep this world however you want it to be?”

* * *

Style (like modern discourse itself) is everything to Killer7. It is a game that engages with every implication within this “quiet invitation” by employing the aesthetic sensibilities of political polarization to recreate, deconstruct and reveal the frame it seeks to subvert. It’s what gives it bite as a work of art, and what makes it indulgent at times to the point of self-obstruction as a work of fiction.

Granted, all Suda51 games have this reputation. When it was released in 2005 over the general consensus of “yes, this looks, in fact, like a videogame”, Killer7 performed self-indulgence to the world the way only one of his joints still does it: extensively, broadly, equitably when it feels like it, never selfishly and always passionately. Most can get something out if they know how to get it. It’s very much like a Kojima game in that way, only that instead of getting eight-hour reflexively deconstructive fan films and someone named “Die Hardman” joining in the middle of the deed, Goichi Suda skips the role-playing (not really) and goes straight into postmodern gratification and disappointing female characters.

And granted, postmodern gratification is very much accounted for in this game. Especially now, when most of it is unintended, in the ways that the global political landscape reflects back on how its stylistic intentions and effects, ironically, mimic the aesthetic trappings of some of the most superficial, effective discourses in the communities that perpetuate our world’s oldest (and newest) systematic oppressions.

“Shit, you’re just a killer after all”

Like every Suda51 game, Killer7 is a narrative experience first, and one in which coherence isn’t a priority nor something the game’s willing to give for free. Plot and exposition limit themselves to the constraints of the protagonist’s profession and the world’s precarious setting.

You’re an agent of the world government (U.S. of A.); seven, to be precise, an “entity/assassin organization known as the Smith Syndicate, aka the ‘killer7,’ managed by its embodied persona and main personality, Garcian Smith, aka ‘The Cleaner,’ and led from the shadows by Harman Smith, aka ‘The Master.’ Your mission – to eliminate every dissenting personality in the geopolitical scene (Japan and else) until the status quo (world dominance) is resumed. Your main target – “Heaven Smile,” a terrorist organization with demonic suicide bombers as their agents, prominent for attacking the United Nations headquarters during the signing of the World Security Treatment, destabilizing the world’s newly unified government.

There is also the caveat of the playable character’s perception being, by nature of its condition, disjointed. The killer7, more than an actual organization, is a series of unrelated personalities residing within a single body (one of them is a luchador). Some present themselves differently depending on who and where the character observing them is, only to later be revealed they were either lying or actual living deceptions. Information suffers the same condition – names and organizations are mentioned matter-of-factly by remnant psyches of past victims (one of them is hanging from midair in a bondage suit while using the words “master” and “tight” a lot) – letters are sent to characters the player won’t meet for a while, describing abilities and backstories from every personality – “allies” point to certain dots and threads without any interest in untangling them because their agendas, like every other character’s, don’t necessarily involve the protagonist.

Details are sparse; understanding isn’t needed: cooperation (needless to say) is mandatory. Your “power” is a tool, nothing more, and the ones in charge will keep it that way until you stop being useful or obedient.

In other words, the perfect conditions for succumbing to aesthetic coercion.

———

Aldo García. Freelance Mexican writer. Semi-professional poser (aren’t we all). Loves some games, adores some films, and is actively bad at both (hence, the posing). You can follow Aldo on Twitter @garciaaldo55.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 170.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!