1979 2019

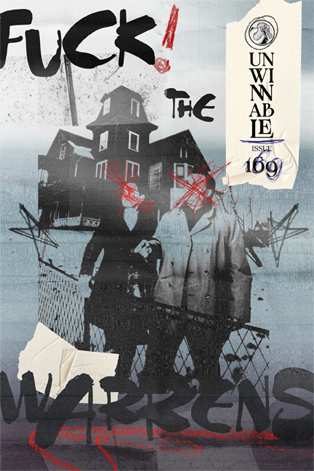

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #169. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Kcab ti nur.

———

This month we turn our attention to Coppola’s 1979 epic Apocalypse Now, and more specifically to its 2019 Final Cut.

Amid a sprawling epic I want to narrow my attention to a part which wasn’t in the theatrical cut but is essential to the film working as an anti-colonial narrative. In the back half of the journey, the central group of American soldiers we follow arrives at a plantation in Cambodia still owned and operated by a wealthy French family who have held the land for decades since the French officially handed over control of the state. The land is guarded fiercely by a group of French soldiers/mercenaries and maintained by Cambodian servants. Once they recognize them as Americans, they give the young Clean (Laurence Fishburne) a proper military burial – what does it mean for a Black teenager a few generations removed from freed slaves to be buried on the ground of a colonial plantation under a flag of stolen stars?

That we are on a plantation specifically is essential for the understanding of what’s happening here. With the development of the plantation in the 16th century from Wales to Ireland to the Caribbean, we move from subsistence farming to highly controlled productions of cash crops, all of which serve to build up Capital(ism) as a system. It’s a form of land use that disregards the needs of both the land and the people beyond a small few – only being created and perpetuated through coercion.

What follows in Apocalypse Now feels almost farcical but cuts to the heart of the colonial mind, perhaps more so than Kurtz’s sprawling monologues delivered by Marlon Brando doing his best American Shakesperean. At the plantation, dinner is delivered by the servants on a long table trying to embody the splendor of a traditional European dinner party for the visiting American soldiers as well as the French living there. It’s a sharp contrast to the explosions and blood we’ve been inundated with, and the place feels like wandering through a dreamer’s corpse. The lighting is dim and sickly, entering in shafts from unflattering angles. You can feel the humidity seep through the artifice of control and you see that paralleled in the conversation at the table.

Dressed in an obviously uncomfortable suit, Christian Marquad’s performance as Hubert de Marais holds this together, moving from faux civilized reminiscing and showboating to frothing vitriol about communists as he laments how far he feels his people have fallen. Specifically, he positions the anti-war protestors back in France as killers of young French men off at war for their refusal to give full support. His performance becomes increasingly desperate feeling, like a vein is about to burst from the stress and hunger of it all. As with the actual France, the conversation at the dinner table makes it clear that there may be room for surface-level disagreement, but ultimately imperium cannot be challenged. All are referred to as “family” by the patriarch, but in reality, only the “true” family (the white English and French) actually speak. Though as has extensively been pointed out by anti-racist critics (Vietnamese ones in particular), some of the same critique can be leveraged at Coppola who mostly treats Asian people as objects through which Western amorality can be skewered – something I would say is the problem reflected in all true Heart of Darkness adaptations when it comes to their treatment of those indigenous to “the Heart.”

In any case, with the frothing anti-communist vitriol the mask falls and so do the myths. Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité. Government by consent. E Pluribus Unum. Plus Ultra. Dear friends, let us love one another, for love comes from God. Everyone who loves has been born of God and knows God. Whoever does not love does not know God, because God is love. All becomes dust and rubble to coat bodies without headstones.

To these imperial powers, the world is their plantation. Racialized people become bodies to do with as they please and exist for the purposes of production and little else. “Family” (or the “global community”) is recreated in the worst sense of the word, a means of ownership masquerading as love and connection. A fraternity with real winners and losers.

I write this as journalists report the IDF dropping white phosphorus in Palestine with planes paid for by the US government and civilians being killed en masse is overlooked by most governments in the West for the sake of protecting their strategic interests in Southwest Asia. I write this as the Congo becomes a battlefield for precious resources because of the greed of local elites and the corporate hand that feeds. I write this as militias in Sudan are armed and given free rein to repeat the ethnic cleansings of less than two decades ago.

If the world is a plantation, then its soil is sick, fed with blood that rots the fruit we eat till the poison makes us lose whatever humanity we had to begin with. Yet still the plantation’s proprietors cling to its persistence even as it destroys over and over. How much blood has to be shed? How many bodies have to be buried under rubble, empty epitaphs and stolen stars for it to be enough?

———

Oluwatayo Adewole is a writer, critic and performer. You can find her Twitter ramblings @naijaprince21, his poetry @tayowrites on Instagram and their performances across London.