What You See in the Dark: Night and Day in Vampire Hunter

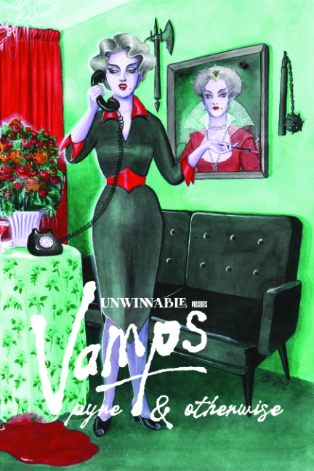

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #168. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

I see board games in the store and they always look so cool and then I buy them and bring them home, I’m so excited to open them, and then I play them, like, twice… This column is dedicated to the love of games for those of us whose eyes may be bigger than our stomachs when it comes to playing, and the joy that we can all take from games, even if we don’t play them very often.

———

Released by Milton Bradley in 2002, Vampire Hunter is part of a robust tradition of battery-powered “electronic” board games – the most well-known of which might be Operation, first introduced in 1965, also by Milton Bradley. These assorted games incorporate their battery-operated components into the game in a variety of different forms, to an array of different effects. In Operation, of course, you remove jokey body parts from a patient using a pair of tweezers connected to a cord. Touch the sides of the incision with the tweezers, and the game buzzes.

The electronic conceit in Vampire Hunter is simultaneously a relatively minor innovation and at the same time central to the game’s play. The subtitle is “The Game That Transforms Before Your Eyes,” and the idea is simple: Vampire Hunter is a fairly straightforward board game with one exception – you play it in the dark. The only light is a plastic tower in the center of the game board, which changes color from red to blue when you push on the top of it.

When this happens, the game board changes accordingly. In normal light, the board looks a bit like it was printed in old-fashioned anaglyph 3D, with board elements represented in both blue and red ink. Naturally, when the red tower light is on, representing daytime, the red elements become invisible, and only the blue ones are shown. Conversely, when the blue light is on, the opposite happens.

On each player’s turn, they draw a card, which tells them whether it is day or night. If it is currently day (the light is red) and they draw a card that says “night,” they hit the top of the tower and change the color of the light to blue, with the board and its various elements changing accordingly.

As you might imagine in a game that’s about hunting a vampire, day is better for the players than night. When night falls, villagers turn into werewolves, clouds of mist become vampires and trap squares appear on the game board – the rules call them “pit traps,” but they’re represented by spider webs. In one of the more clever uses of this relatively simple gimmick, the die that players roll to move their character is also printed in two colors, meaning that your rolls are much higher in the daytime than they are at night.

Without the day and night conceit, the game is straightforward indeed. You move around a board, which is divided into four sections – a graveyard, a marsh, a dining room and a crypt; the four areas that all castles have. Within each of these are several tiles which you turn over as you approach them. Some are enemies, others are weapons. You’ll need to collect one of each kind of weapon and reach the final area in order to slay the master vampire, whose name is Drakus (they were not trying terribly hard) before his boat arrives and he departs, presumably for England, given what we have to work with here.

Ostensibly, the player who finished Drakus off is the “winner,” but really this is a purely co-op game in which players work against the board. In the same way, it says that it can accommodate 2 to 4 players, but could just as easily be played solo.

But would you want to? Eh, probably not really. Like many of the electronic games that live and die by their gimmicks, there isn’t really much to Vampire Hunter besides that red/blue light trick. As a game, it plays pretty quickly and there’s not a lot of variety. In fact, you could handily memorize where the trap spaces are during the “daytime,” making it easy to avoid landing on them at “night.”

The real question with a game like this is less “how is the game” and more “how does the gimmick work?” And, again, the answer is a mixed bag. The basic idea here is similar to the trick that William Castle used in the original 13 Ghosts, where looking at the screen through either red or blue filters made the ghosts appear or disappear. As in that case, it sounds more fun on paper than it really is in practice, though there’s a real (if short-lived) pleasure to it in both. More damning here, though, is that the red/blue gimmick only works about half the time.

When what you’re seeing is something that is simply printed in one color that appears or disappears with the changing lights (the trap squares, the different numbers on the die) it works like gangbusters, and there is a sense of magic to the extent that one thing vanishes and the other shows up. However, that’s only about half of the two-color items involved in the game. Others superimpose two images over the top of one another, so that villagers transform into werewolves, or so that Drakus himself turns to bones and dust when he has been slain. These work considerably less well, with the dual images muddying one another, regardless of which light is shining.

There’s one other, bigger problem with the core idea of Vampire Hunter, though. You’re supposed to be playing in the dark, with only the tower light illuminating the board – though the instruction booklet does suggest maybe turning on some night lights so that you don’t crash over something when you get up to go get a snack or whatever. And if there’s too much ambient light, the two-color tower light won’t do its job on the board elements. Problem is, at least in the version of the game I was playing, the light isn’t really bright enough for that.

Sure, you can kind of see what’s happening on the board, and the designers of the game were smart enough to make the bases of the different vampire hunters different shapes, so you can quickly identify your character, even in the semi-dark. But if you want to make out what’s on a tile when you turn it over, chances are you’ll have to hold it up near the tower – especially if you want to really see the red/blue effect.

Vampire Hunter has been out of print for a while, for probably good reasons. It’s not really worth tracking down. If, like me, though, you find a cheap used copy at a Half-Price Books, say, then it’s a fun game to play, like, twice, especially around the Halloween season, when the idea of playing games in the dark takes on an added thematic resonance.

———

Orrin Grey is a writer, editor, game designer, and amateur film scholar who loves to write about monsters, movies, and monster movies. He’s the author of several spooky books, including How to See Ghosts & Other Figments. You can find him online at orringrey.com.