Don’t Fear the Reaver

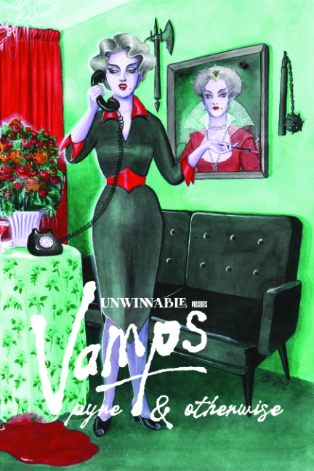

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #168. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Analyzing the digital and analog feedback loop.

———

I grew up in a world of vampires. That sounds intense and gothic, but I assure you, it was actually quite mundane. Comforting even, in a strange way. Vampires were some of my most sincere tutors, even when they thought they were being mysterious and deceptive. Lestat and Louis taught me about the complexity of morality. Simon (of the criminally underrated YA novel The Silver Kiss) taught me about loneliness and mortality and how neither of those were as scary as being caught in a purgatory. Especially one of your own making.

Meier Link taught me that sometimes those who call themselves righteous protectors can be just as cruel and predatory. Vamps and Dhampirs had the potential to be in some instances, if not heroes, then anti-heroes at least (as tired as that category of protagonist may seem today). And as such Blade and D taught me to reflect on what makes people label others as monsters and to be wary of how you internalize your sense of alterity. Practically every woman vampire I encountered taught me, from Lucy and Dracula’s wives to Carmilla and Akasha (portrayed best by the radiant Aaliyah, may she rest in peace) that embracing your differences can be your source of strength. The vamps of What We Do in the Shadows (both the movie and tv series, though I’m more familiar with the former) taught me not to take myself so seriously and spend more quality time with friends and loved ones.

Above all vamps have taught me that any relationship I enter, whether familial, platonic, romantic or otherwise, has the potential to drain me if I’m not aware of my limits or boundaries. Both physically and mentally. Although the classic sanguine tales of vampires are fascinating to me, I’ve more often been drawn to the emotional beats of any vampire story. Some vamps don’t just drink your blood, they can siphon your energy too. Sometimes they even steal or change your soul. These types, both in and outside of folkloric spheres, are referred to as psychic or energy vampires.

I think many of us recognize a psychic/energy vampire when encountered with one, but they’re usually not definable by shared physical characteristics (although this humorous old article from the golden age of Twilight claims otherwise). Even Colin Robinson of the aforementioned What We Do in the Shadows tv series and his fellow energy vamps are physically cast as the most nondescript pedants of society. Most sources describe energy vampires primarily by their psychological profile as individuals who drain you of your emotional energy and who saddle you with their emotional labor. In other words, such vamps are chiefly identifiable by the toxic feelings they evoke and by the exhausted aftermath of putting up with their antics. Another commonly stated characteristic is that they are not always intentionally hurting others, including those close to them.

The metaphorical language surrounding this relationship dynamic is interesting to me because often there is no mention of how one becomes an energy vampire. Although the intention of such language is meant to focus on educating vulnerable individuals and keep them safe from such people, there’s a sense of othering associated with categorizing energy vampires as if they are pre-existing entities without a point of origin. Or if sources do discuss origins, such individuals are quickly summed up as those who drain others because they’re dealing with their past trauma in an unhealthy manner, have pre-existing mental health issues or certain attachment types.

Similar to those with highly stigmatized disorders such as narcissism, schizophrenia and dissociative identity disorder, energy vampires’ pop psychology descriptions exclude or understate a vital part of their narrative. When we know how energy vampires are made, we are made aware of how perpetual cycles of abuse and stigma can be halted. And I’m by no means blaming the victims of energy vampires here (I’ve definitely been one of them over the years). I’m merely interested in avoiding reductive descriptions of people that can incidentally do more harm than good. Not to mention the fact that such reductive descriptions can obscure the fact that while some people epitomize the energy vampire archetype, the existence of such an individual is fairly common.

Raziel, the tragic wraith protagonist of the Soul Reaver series, contains within his arc a nuanced portrayal of how an energy vampire is made and unmade. He is also recognizable on sight as an energy vampire, a walking bundle of raw sinew and nerves. His trauma is etched into his body and as the Elder God of Nosgoth’s Underworld puts it, he has a “deeper need” than other vampires. It’s no wonder that he does either, his betrayal by his King/Father figure Kain, was so complete and so visceral. For the trespass of evolving a set of wings which symbolized his daedalic ascendance in power above Kain, Raziel is cast into the Abyss and consigned to the Underworld after having said wings brutally ripped off by his liege. This traumatic experience twisted Raziel into a creature that, while first despondent of his fate, quickly learned to survive at all costs, even if it was solely for revenge.

Throughout his journey, Raziel must suck up the souls of those he fights to sustain himself, including those of his brothers and even himself in another timeline. Before he was turned into a vampire general by Kain, he lived the antithesis of this existence as a vainglorious Sarafan Priest. He was a self-righteous crusader who endlessly blathered about his divine quest to rid the world of vampires. In addition to the delicious poetic justice of Kain turning such an individual into the monster he hates, Raziel’s human side illustrates the more common sort of energy vampire – the sort of person, like Colin Robinson, who can suck the air out of the room with their tedious and arrogant presence. Though to be fair, Raziel as the Elder God’s Angel of Death was equally prone to naive monologues and soliloquies. The difference being that in addition to morality, Raziel was understandably fixated on fate and causality.

Wraith Raziel was, for many players who were angsty teens like me when they played Soul Reaver for the first time, strangely compelling however. His tragic introduction inspired an initial wave of pathos that, for those empathetic to his suffering because of a tyrant’s rule, made them more than willing to follow and help Raziel along his voracious path towards avenging himself. Raziel fans, especially those who were new to the Legacy of Kain series, were sometimes deeply obsessive about the character. One internet shrine I came across back in the day professed love for the character and admitted that they knew others wouldn’t understand such an affection for a fictional person.

Today such an attachment is much more recognized as related to phenomena like fictosexuality, fictoromance or fictophilia, in which a person truly loves, desires or is infatuated with a character. The most common instance people know of is Akihiko Kondo, who married a hologram of Hatsune Miku and identifies as a fictosexual. I won’t say that the internet shrine’s maker was any of those terms, it’s unfair of me to assume and I’m in no position to pathologize anyone (nor would I even if I was). But suffice to say, Raziel’s reaving reached beyond even the confines of the game, drawing from the player’s emotional or psychic energy.

As Strictly Fantasy has noted in one of his series of video essays on the Legacy of Kain series, Amy Hennig smartly wrote Raziel as a protagonist that would appeal to a new generation of players. But he was also conceived as a character that would act as a foil to Kain and his cruel (yet earnest) schemes to free Nosgoth of a notion of fate that forces individuals to sacrifice themselves for the sake of the many. Raziel often does the right thing for the wrong reason and he is preyed upon by cosmic agents like the Elder God and the Time Streamer Moebius, who offer him false binaries such as to redeem or avenge himself.

Raziel eventually has another major revelation about his existence – that Kain threw Raziel into the Abyss as a desperate yet calculated gambit to thwart those who rule over the spiritual and corporeal realms of Nosgoth. To prevent history from being dictated by those who believe fate is more important than free will. By destroying a sanguine vampire as powerful as Raziel, he was able to be remade into a being that was unfettered by fate. Let me be clear that I don’t mean that Kain’s actions are morally right; that would be akin to saying that abusers with good intentions are morally right. But what this revelation does highlight is that Raziel’s existence as an energy vampire is not something that you can easily pin down. He is both victim and victimizer, a redeemer and a destroyer.

In Legacy of Kain: Defiance, the final entry before the series went into its current seemingly endless hiatus, Raziel meets his end by his own hand. He realized that the only way for him to reveal Kain’s true enemy is by purifying the physical Soul Reaver blade with his wraith’s soul, uniting the spirit world with the corporeal world once more (that’s the short and simple version, believe it or not). He is able to forgive Kain for his transgressions, but not because of a sudden pang of sympathy for his abuser. For perhaps what is the first time in his arc, Raziel makes a decision based on reason instead of emotionally acting out of his history of violence and trauma. By choosing outside of the endless binary choices presented to him by others, Raziel sets himself free and by extension gives Kain a chance to also free the rest of Nosgoth from its dictators.

I cannot say forgiveness is the sole thing that could unmake an energy vampire. I do think, however, that being able to reconcile oneself with what made them one could ameliorate one’s circumstances considerably. Kain and Raziel taught me about boundaries and respecting one’s right to free will, while recognizing that championing free will alone does not make someone morally right in every instance it’s invoked. We all live in a world of energy vampires these days and every one of us has the potential to become one.

———

Phoenix Simms is a writer and indie narrative designer from Atlantic Canada. You can lure her out of hibernation during the winter with rare McKillip novels, Japanese stationery goods, and ornate cupcakes.