Object Lessons #2: Smartphone

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #167. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

What’s left when we’ve moved on.

———

This month I’m thinking about smartphones. Not smartphone games – I don’t play any regularly, unless Duolingo counts – but how phones are represented in videogames on other platforms.

I wrote last year about the trend of games trying to be multimedia (in this case, being more like TV/movies) and how I think this has the potential to overlook what makes games special, their ability to react in a limited way to player choice. In that game, We Are OFK, characters communicate via texting; your (only) method of choice is choosing a response. In addition, the game uses texting language to qualify its characters’ age and social class. I think it fails in this regard, as the characters don’t come across super believable to me; but in any case, phones are the only way for players to change the game, and the main way for characters to contact and speak with each other. They’re the crux around which the game is built and also your window into it.

There are probably countless games that represent cell phones that aren’t of consequence to the player. Games about modern life basically have to represent smart phones in some way. But if the phone is functional, often it’s for texting your friends, like in OFK or Persona 5. In Dave the Diver, it’s where you order fishing equipment and look at achievements, while in Neo Cab it’s your road map to pick up and drop off your customers. Personally, I probably use my real phone most as a map. Breath of the Wild did this by giving you a mini-Switch (tablet) with apps that operated like a phone camera, map, etc.; the Witcher series didn’t give you a device, but it did have a (very helpful) Google Maps-ish function that showed you the direct path to your next objective. Pikmin 4 does the same thing, but back on the phone (tablet).

But other uses of phones are underrepresented in games. Apart from tracking your location, a phone is also a diary, a game console, a list collection and a work assistant. But game phones often confine themselves to representing two of those functions: texting and locating yourself in space.

Recently my boyfriend started tracking his steps on the rings app on his iPhone. On days we spend together, that means he’s also tracking my steps. I’ve been surprised how weird this feels, like someone watching me exercise. I thought it was the first time I gave an app permission, on purpose, to enter my thoughts and make my phone more than a phone – in this case, a pedometer.

And then I played Eliza, which is based on a therapy simulator, and I remembered I actually did this before, in a phone app called CBT journal. The app asks you to pick one of five faces, from crying to happy, then rate your mood, then describe the problem you’re facing and how you want to solve it. It’s supposed to help you track your moods and see any cognitive distortions you have. No, I’m not using AI therapy – and I deleted the app last year, mostly because it was clear I was using it to give my problems more mental real estate, not try to solve them.

Eliza reminded me of CBT journal not because it’s about digital therapy, but because there’s an app on the main character Evelyn’s phone that’s for relaxation. It first gives you a shot of lanterns that says in text “Think back to what brought you here”.

The place of the smartphone in games is to be a window into the world of the person holding it. If I were a digital person, and somebody had my journal with the five faces, I shudder to think of what they’d say or do. This comes through in Eliza, because Evelyn has to look through other peoples’ phones in “Transparency Mode.” The first person you look at, an artist named Maya, is unhappy and wants to be creatively successful; all her emails are rejections and an uber cleaning bill. The information is mostly boring, but the experience of looking at it is surreal. The game positions this as a breach of personal privacy, though not everyone in the game sees it like that.

Then again, smartphones are used as literal windows. There’s AR, which I remember using on my 3DS in 2011, and which has become part of apps like Replika. Then there’s detection, where you can identify a type of tree, for example, by scanning it. I’ve talked to people about that particular app on walks several times, but never used it. I’m still not used to Google Image Search, either. The idea that technology can so cleanly scrape the real world doesn’t go down smooth with me.

Aside from the scanning thing, games seem to prefer to keep their phones simple. How do you represent a technology that’s had an earthquake’s impact, that almost everyone owns and that has made our private lives public (though talking about that shift remains kind of annoying, at best)? Games seem to still be figuring that out. Phones are either a representation – pixels that show someone making a call or texting – or they’re the mechanic through which you set up the game, ordering delivery or texting or whatever. You don’t play the game through the phone; you use the phone to do other stuff than play the game.

Maybe that’s truest to life. As I wrote this article I 1) checked Bluesky, 2) sent several Whatsapp messages, 3) listened to a podcast series about delivery drivers, 4) checked my email, 5) paid my gas bill, and 6) checked out an e-book from the library. I probably did plenty more that I forgot about. My phone has become an extension of me, as much as I resent that.

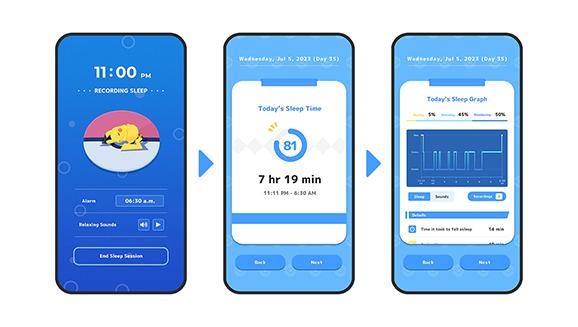

Collectively, we’re questioning how apps and AI affect our personalities and how we navigate the world. When I’m feeling paranoid, I think that the normalization of smartphones as interfaces in games is training us to accept them as the default mode of interaction with the world. Pokemon Sleep freaks me out. The activity rings, still, freak me out. But I’m not doing anything about it, even in my own situation.

Do I even want games to tell me to my face how much of my privacy and time I’m handing away? Are they even the right medium? I think I’d find that imagined, “phones are bad for you” game more odious than even the faux-Gen Z texting game. But what I’d like games to do isn’t eliminate phones; just make them more noticeable, give them friction. Treat them like a tool you have to use, and make their limits and frustrations more noticeable. Right now, phones in games are fantasies of phones, almost ads for phones. I want them to be worse, push back more; I want them displayed in 3D. Give me a shitty phone. Let me figure it out.

———

Emily Price is a freelance writer and PhD candidate in literature based in Brooklyn, NY.