The Music and the Dice

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #166. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

The Burnt Offering is where Stu Horvath thinks too much in public so he can live a quieter life in private.

———

Two hour and 44-minute companion playlist

1.

There are notable similarities between playing a tabletop roleplaying game and playing music in a band. In most cases, it takes a group (though solo play isn’t out of the question) and the proceedings are collaborative. In Dungeons & Dragons, the Dungeon Master runs the game and serves as a sort of drummer, keeping the beat and drawing the game inexorably on, while the players, each in a unique role, contribute to the drama in a series of semi-mathematical causes and effects. There are solos and harmonies. And, like any live performance, its greatest power resides in the moment, experiencing the event as it happens. Describing the action after the fact, to someone absent from the heat and the press, always seems flat. Abstract.

2.

Iron Maiden was the first band I discovered that seemed to make music expressly for Dungeons & Dragons. This was in 1989, a propitious time to encounter the band, as the whole catalog of their heyday albums was already on store shelves. I was in 6th grade.

As a child reared on ghost stories and monster movies, there was little chance I wouldn’t be drawn to heavy music, with its trappings of grim reapers and demons and spooky face paint. After a couple bleary-eyed Saturday nights watching Headbanger’s Ball on MTV, I was trapped in the web. A friend let me dub his Metallica tapes (take that, Lars!) and I owned a legitimate copy of Guns N’ Roses’ Appetite for Destruction, an album that, thanks to all the cusswords and the lurid interior painting by Robert Williams, practically crackled with forbidden energies. Maiden sorta fit those newer bands, mostly in the surface aesthetics—Metallica’s Kill ‘Em All features a bloody hammer, Appetite has that Williams painting and Maiden’s Killers is, well, called Killers and features the immediate aftermath of an ax murder on the cover. But I fell in love with the differences.

Where most ’80s metal is gloomy or driven by aggression and bad behavior, Maiden’s music is bright and often triumphant; it wants to soar. And though hardly clean cut, Maiden stands apart from much of the debauchery that characterizes heavy music of the era. Appetite for Destruction features a song about a brand of fortified wine and moans recorded during a sexual encounter in a recording booth. Meanwhile, Maiden’s primary songwriter, Steve Harris, draws inspiration from science fiction novels, horror movies, surreal British television programs and the poetry of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. The lads certainly got up to mischief, but that wasn’t reflected in the nerdy content of their music (well, mostly – they’ve a trilogy of songs about a sex worker named Charlotte who eventually hooks up with a motorcycle-riding devil, but those seem quaint compared to even the tamest of Guns N’ Roses songs).

Perhaps because of this literary wellspring, Maiden’s music seemed to sync perfectly with Dungeons & Dragons (Gygax, after all, famously listed his favorite fantasy novels in Appendix N of the Dungeon Masters Guide). This isn’t in the details – Maiden has no songs about fighting monsters and stealing their treasure – but resides entirely in the domain of vibes. The band’s music captures the feeling of the game, the derring-do, the danger, the clash of swords. “Flash of the Blade” turns the frenzy of hand-to-hand combat in a laughing sort of riff, but more importantly, and unwittingly, it captures the true spirit of roleplaying games with its opening lyric: “As a young boy chasing dragons, with your wooden sword so mighty, you’re St. George or you’re David and you always killed the beast.”

3.

It’s easy to think of heavy metal as the cool older brother of Dungeons & Dragons. While the moniker was used earlier, “heavy metal” as we recognize it today coalesces in the opening chords of the song “Black Sabbath,” recorded in 1969 by the band Black Sabbath, for their debut album, also dauntlessly named Black Sabbath. Those notes ring out with metaphysical menace, which only grows as the song’s tale of occult peril unfolds. This is exactly the sort of stuff that stoked fearful Bible-thumpers into a moral panic in the ’80s.

The success of Sabbath, coupled with the Tolkien-inspired songs on Led Zeppelin IV (“Misty Mountain Hop,” and “The Battle of Evermore”), kicked off a wave of bands that made heavy music preoccupied with fantasy, horror and the occult. For every Iron Maiden, there was a score of obscure acts: Especially in the United States, high school kids with some weed and a pile of moldering Robert E. Howard paperbacks were inclined to lay down some riffs. Numero Group’s Warfaring Strangers: Darkscorch Canticles (2014) collects sixteen tracks from long-forgotten bands with names like Gorgon Medusa, Stone Axe and Wizard. It’s all painfully naïve and imitative, and only passably listenable, but it demonstrates a real underground current in the ’70s that was fusing heavy music with fantasy.

That relationship would become even more deeply entwined aesthetically and commercially in the ’80s. Cirith Ungol took their name from the home of Shelob the giant spider in The Lord of the Rings and, as if that weren’t enough, also recycled the Michael Whelan paintings from Michael Moorcock’s Elric novels for their album covers. Blue Öyster Cult went a step further and had Moorcock co-write a song, “Veteran of the Psychic Wars.” Manowar’s reputation was partly built on their enthusiasm for Conan cosplay. When the underground English band Slayer ran into trouble with the American thrash band of the same name, no problem, they just became Dragonslayer. Dio, meanwhile, battled an animatronic dragon on stage every night as part of his live show.

The silly camp of metal’s embrace of fantasy was lost on the evangelical Christians behind the Satanic Panic, who conflated fantasy imagery with occultism and diablery (granted, all three flavors were routinely embraced by metal acts as intentionally transgressive – even Iron Maiden has the devil on several album covers, though he is eventually beheaded by their mascot, Eddie). Thanks to shared aesthetics, a certain enthusiasm for demonic imagery and a zest for ambiguous moral systems, Dungeons & Dragons also fell afoul of allegations that this stuff was somehow dangerous to children, which further bound the game to heavy metal (and generated a lot of publicity and sales, despite the headaches). I suspect the scandals made RPGs more attractive to metal musicians; by the end of the ’80s, the influential band Kyuss was comfortable taking its name from an undead monster from the Fiend Folio and the death metal band Bolt Thrower became the semi-official soundtrack of Warhammer 40k when they used John Sibbick’s art from the rulebook as the cover of their 1989 album Realm of Chaos (a title shared with a line of Warhammer books and miniatures).

4.

It’s mighty tempting to theorize that heavy music influenced the creation of Dungeons & Dragons. Alas, D&D was created by squares.

In 1972, the year the pair began their collaboration on what would become the first tabletop roleplaying game, Gary Gygax was 34, married, had five kids and had lived for most of his life in Lake Geneva, a resort town in Wisconsin. In 2001, he told RPGnet, “I listen mostly to classical, Spanish guitar, jazz, and some blues too. Of composers, I am drawn to Mozart and Beethoven. Segovia surely was master of the guitar, and the ‘modern’ jazz musicians are my favorites – Parker, Davis, Gillespie, Hinton, Rich, Anita O’Day, Billie Holliday, Stan Kenton – all that lot.” Dave Arneson was 27 and resided in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area. I’ve found no interviews that mention Arneson’s musical tastes and the closest I can find to a Minneapolis metal band in the ’70s is Hüsker Dü, which formed in ’79 and isn’t very heavy at all, despite the umlauts.

5.

The Bard is a character class in many versions of Dungeons & Dragons who sometimes has a connection to music. There is little consensus across the editions as to just what a Bard is or does, however. Sometimes they are loremasters or musicians or poets or mere jacks-of-all-trades, inspired, variously, by Will Scarlet, the Pied Piper of Hamlin, the Norse skalds, Taliesin, the troubadours, travelling minstrels and that noted Greek mercenary, Homer. There is no official Bard class in the original D&D and the one Gygax included in his Advanced version is essentially unplayable.

6.

While working on my book about tabletop RPGs, Monsters, Aliens, and Holes in the Ground, I interviewed James M. Ward, designer of an RPG called Gamma World (1978). It’s the first post-apocalyptic RPG, set in our own world after an unspecified cataclysm allows mutants run amok. These themes spring from a rich tradition in science fiction, but Gamma World is often a silly game as well. That sense of humor made me wonder if Ward was a fan of Devo. The art punk band emerged from Akron, Ohio, in the mid-’70s with a catchy combo of deadpan humor and a preoccupation with mutation that seemed similar to Gamma World.

Not only did Ward profess to not be a fan of Devo, he seemed perturbed that I even proposed such a connection.

7.

On the cover of the Gamma World Referee’s Screen (1981) is a painting by Erol Otus that features a barbarian woman with a laser weapon and a hairstyle that can be credibly called a tri-hawk. She has a little eyeball friend, and they are looking out at a landscape of bizarre aspect, but the most jarring thing in the composition, is the medallion she wears on her chest, which is clearly the red and silver logo of the Bay-area punk band Dead Kennedys.

“I liked the Dead Kennedys and I thought their logo would make a nice amulet,” Erol explains. “I have a rebellious streak and it appealed to me to put it in knowing none of the TSR management would have any idea what it was.”

8.

A few games in the ’80s nodded to the nightlife. I’m confident many a session of Chaosium’s Stormbringer (1981) began with the needle dropping on Deep Purple’s song of the same name. A scenario for Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Other Strangeness (1985) is set during a performance by a band called 666, and an adventure for the horror game Chill called Death on Tour (1985) features a vampire using his band, ironically named Van Helsing, as a cover for his feeding. Cyberpunk (1988) and Shadowrun (1989) both incorporated the aesthetics and attitude of punk, goth and new wave wholesale.

In the ’90s, people who took part in both musical subcultures and roleplaying games found themselves making RPGs that directly reflected their musical experiences. The first was the aptly titled Nightlife (1990), which saw monsters of all sorts partaking in the New York City club scene; one sourcebook, In the Musical Vein, assumed players would form their own band. The rulebook for the Swedish RPG Kult (1991) is peppered with quotes from bands like Killing Joke and Sisters of Mercy that inform the tone of its metaphysical mysteries.

White Wolf’s Vampire: The Masquerade (1991) hit the clubs the hardest. Similar to Nightlife, the game proposes that a secret world of vampire clans and conspiracies exists in the shadows of every city in the world. Thanks to the gritty, photo-realistic art of Tim Bradstreet, Vampire fully embraced a gothic punk aesthetic unrivaled by other games (to the point that the company trademarked the term “Gothic-Punk”). Vampire was so successful that it purportedly outsold D&D for periods of time, a feat no other game had accomplished before. Perhaps even more impressive, it inspired enthusiasts to organize real-world “vampire” courts in some cities that paralleled the fiction, a live-action roleplaying experience that made good on the game’s promise of a world hidden in from mundane club-goers.

9.

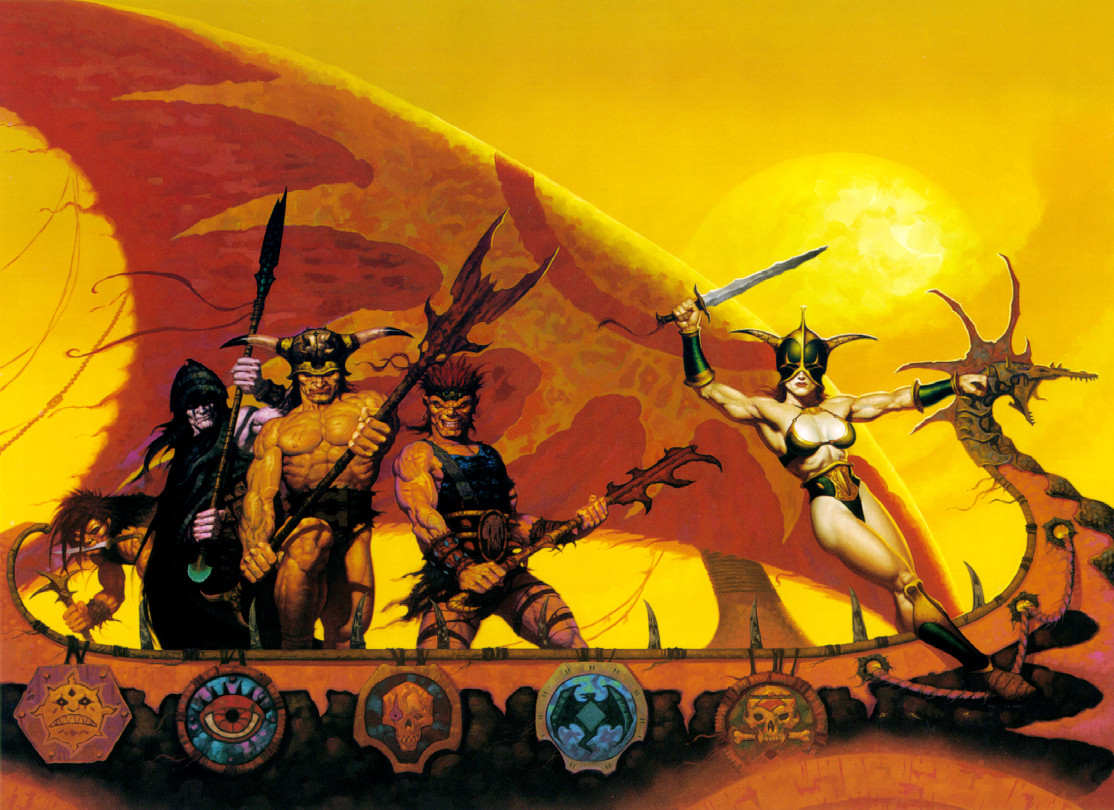

Dungeons & Dragons wasn’t immune to the rise of music scenester. The Dark Sun campaign setting (1991) was aesthetically defined in large part by the art of Gerald Brom. Looking at his work, which often features mohawks, piercings, unusual make-up and what can only be described as fantasy versions of BDSM gear, it’s no surprise that his bio namechecks a long list of bands like Gun Club, Joy Division, The Damned, Black Flag and many more.

A few years later, TSR released the metaphysically complex Planescape campaign setting (1994), which embraced a look in line with industrial music, complete with rusted and verdigris metals. My own Planescape campaign used Danzig’s quasi-industrial instrumental album Black Aria (1992) on repeat as its soundtrack. I felt like the Universe was winking at me when I recently learned that Tony DiTerlizzi, the setting’s primary artist, drew many of his illustrations listening to the same album.

10.

These days, the web of connections is so dense it’s difficult to untangle who is influencing who. Tales from the Loop (2015), which mixes nostalgia, science fiction and mystery in ’80s-era Sweden, encourages players to select a period-appropriate theme song to help define their characters. Ultraviolet Grasslands (2020) advertises itself as a psychedelic heavy metal road trip where players might pass monolithic statues of hands throwing the horns. MÖRK BORG (2019) calls itself a doom metal RPG and issued a supplement, Putrescence Regnant (2021), that includes an LP full of ominous, ambient music; Greg Anderson of drone metal outfit Sunn O))) lays down thunderous guitars on one track. The same year, experimental metal band Kauan released Ice Fleet, which includes a thematically linked scenario complete with its own simple RPG system. Game authors regularly list albums that inspired their work. The word “punk” has become a workhorse genre suffix.

In the ’70s, RPG-theming in music was coincidental, but now it’s often intentional and blunt. In 2003, Slough Feg cut an epic concept album around the classic science fiction RPG Traveller, and not only used the game’s aesthetics for the album art but just titled the album Traveller! Dungeon Weed has a song called “Beholder Gonna Fuck You Up,” a plain-spoken reference to a classic D&D monster that is basically a ball of floating eyes that will, indeed, fuck you up. There are subtler efforts, too, like the albums of the Swedish adventure rock band Hällas – the band shares their name with the central character in the lyrics, a knight who journeys through time and space. Their crisply clean sound evokes a kind of anemoia for memories of a perfect ’70s gaming table that never existed, or perhaps did in a parallel universe.

Last October, I checked out a metal showcase at TV Eye, a club in Queens. The three bands I saw all embody this new fusion between the nerdy pursuits of fantasy fiction and roleplaying games with frankly blistering metal. The first was Zorn, purveyors of crusty black metal; I’ve since traded some vintage Grenadier miniatures with the singer for a t-shirt. Shadowland performs clean, classic-style heavy metal that is a rarity these days – during the performance, singer Tanya Finder teasingly asked the audience if we liked Elric before launching into a song about one of Michael Moorcock’s lesser-known protagonists, Ulrich von Bek. Even Final Gasp, a deathrock outfit inspired by Danzig’s old band Samhain isn’t too cool for tabletop – they may come out on stage covered in blood, but their first EP has some artwork that looks similar to Keith Parkinson’s cover painting for the D&D module H4: The Throne of Bloodstone (1988), which implies deep knowledge of the hobby (and good taste).

11.

The thing about music sub-cultures is that they often exist as places of escape for folks who don’t fit in with the primary culture. It used to all be shoved under one big umbrella – “the counterculture” – but it has becoming increasingly clear that there are many ways to be, and each of those ways merit their own sub-culture where folks can find belonging, or at least a shared experience reflected in the rhythm of a song. It’s because of this ability of music to bring people together that folks often call it a universal language. Music also trains us to accept different things over time; a song that was once transgressive naturally becomes prosaic. Throw on a punk record from ’77 and see how these songs that were so caustic at the time, that were specifically designed to fly in the face of convention, have become rather inoffensive. It’s easy to hear the influence of ’50s and ’60s rock. It’s surprising how mid-tempo these supposed thrashers tend to be.

I don’t think it is a coincidence that as the RPG hobby grew to reflect different sorts of music, the diversity of people creating and playing have similarly increased over time. The US version of Kult, a game wrapped in musical references, was imported by Terry K. Amthor, one of, if not the only, openly queer designer in the hobby at that time, and it’s one of the earliest RPGs with clear queer themes—characters live in two worlds, an apparent one in which everyone exists, and a secret, more true one that is both dangerous and rewarding to explore. Since then, queer themed games, by queer creators, have grown to become a sizable slice of the contemporary RPG scene. A similar phenomenon has been taking place in the last ten years, where games using various punk suffixes—afropunk, hopepunk, solarpunk, and so on—have been used to make room for Black and indigenous cultures, often drawing on themes prevalent in hip-hop and its own varied musical sub-genres (a long overdue phenomenon—hip-hop is underrepresented in previous decades, even in urban, street level games like Cyberpunk or Underground).

12.

Out there, time slows down. In here, I becomes we, and the whole is stronger for it. It moves together, with a purpose, and time is plastic, faster, juttering, smooth, a dead halt, according to need rather than physics. There’s meaning, even if it isn’t plainly spoken, even if it’s just a feeling that needs to be trusted. Music, games, out there, it’s just reality; in here, it’s the whole world.

———

Stu Horvath is the publisher of Unwinnable. He reads a lot. Follow him on Twitter @StuHorvath.