Architectural Intent

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #166. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Interfacing in the millennium.

———

The premise of Arkady Martine’s Rose/House is a haunting. Not a ghostly one – nothing supernatural is involved – but nonetheless a specter of the dead continuing to leave fingerprints, affecting the world it used to inhabit. And like all good hauntings, of course, it needs a house. Therein lies the problem.

Here is the rough plot of the book: Rose House, the masterpiece of the architect Basit Deniau, has been locked up since his death. The exception is his executor, Selene Gisil, a former student who hates him, who is allowed one week a year in his archives. A dead body appears on the premises, impossibly. Rose House informs the local police department, due to some Asimov’s law-type strictures baked into its codes, and then spends the rest of the book intentionally impeding the investigation, occasionally quipping and threatening in a manner unconvincing from a system we’re supposed to believe can be genuinely manipulated by logical loopholes. At some point within the 150 pages there is somehow time for a subplot about the detective’s partner, a shady journalist, some questionable art dealers and, bizarrely, the Andorran government. Gisil stays reticent and unhelpful; Maritza Smith of the China Lake Police Precinct tries gamely to solve her murder mystery.

Part of the reason Rose/House struggles is that for a book that is nominally about the hubristic imaginings of a genius architect, it seems to have no actual interest in architecture. The descriptions of the house itself stay frustratingly vague, tending towards the non-Euclidian in the tradition of House of Leaves – but where House of Leaves‘ house-turned-labyrinth was implied to be almost an organic phenomenon, self-perpetuating and expansive, Rose House is supposed to be intentional. The design is the point; everything about the building of Deniau’s myth leads us to believe that it is his work, his art and his creative process that leads to the genius and remarkable nature of Rose House. We are told this, however, but not shown it, and in fact as the book progresses it seems more like Rose House’s uniqueness is not in the architecture at all but in the AI that lives within it, the one that talks and schemes and protects what is left of Deniau’s mortal form long after his death. We are told that Rose House and the AI referred to as Rose House are one and the same, but in practice they are meaningfully different – Rose House the AI can control the functions of Rose House the building, but it still relies on nanobots in order to manifest itself physically (which one would think would not be necessary were the house itself its physical form), and the art dealers whose attempted theft makes up one of the more important subplots are attempting to steal not, importantly, the blueprints of the house itself, but the algorithms that gave it life – attempting to replicate the AI, which is not the house.

The irrelevance of the house itself to Rose/House is at odds with the theme it seems interested in exploring, that of the symbiotic relationship between architect and architecture, and between architecture and inhabitant. What relationship does the occupant of a space have with the space itself? Can architecture influence action? The haunting, as Rose/House seems to present it, has to do with the danger within the house itself, where visitors are necessarily at the AI’s mercy – but by falling back on the internal mechanism of an artificial intelligence, the question that was initially asked about the role of architecture is being ignored. It ignores the traditional approach of genre predecessors like The Haunting of Hill House – where the house’s simple existence, its inhumanity and still its ability to influence and torment its occupants, is the source of horror – and also shows a lack of interest in engaging with the theories of social architecture, how built space affects the people within it, a topic that has been written on for decades.

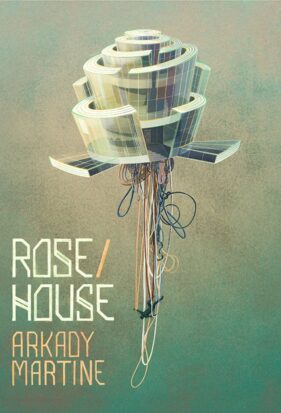

The cover of the book brings to mind another story with similar thematic interests. Rose/House as depicted in this artwork – not, mind, how it’s actually described in the story – is a prismatic glass rose, beautiful and surreal. The Polyhedron in the Pathologic games is almost identical: it rises above the town where it was built like a spindle, impossibly, in defiance of geometry and gravity. The Polyhedron, too, is an exercise in architectural hubris, that nearly destroyed the architects that built it and unknowingly condemned the town to plague and despair. Instead of the isolated, claustrophobic insularity of Rose House, though, the Polyhedron is actively inhabited, and its influence spreads outward into the community where it was built instead of being restricted to within its walls. Pathologic recognizes the power of monumental architecture and uses it to show how the Polyhedron stretches its fingers out through the community that looks up to it; Rose/House, on the other hand, seems to understand that residential architecture directs and effects the people that live within it, but expresses that as “the house can talk and tell people what to do” instead of exploring the deeper, more complicated approaches to that theme.

On one hand, Rose/House is a compelling idea, and a fresh take on the haunted house genre. It crosses through genre carelessly, and Martine’s ability to clearly and vividly craft a plausible sci-fi world is on full display. Deniau’s character, at his baseline, is engaging – European Frank Lloyd Wright, basically, mercurial and widely lauded and emphatically unlikable – and Rose House’s loyalty and affection towards him even in death is satisfying uncomfortable. But it’s hard not to read the vagaries of the book as lack of interest, and frustrating to see a talented author seemingly so lost as to the actual story they were writing. Like Rose House itself, we’ve been told that the design is intentional, but it just doesn’t seem entirely convincing.

———

Maddi Chilton is an internet artifact from St. Louis, Missouri. Follow her on Twitter @allpalaces.