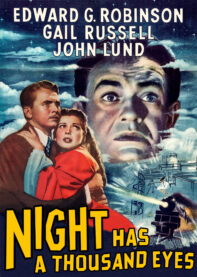

The Stars Can’t Hurt You: Fighting the Future in Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1948)

“I never had much luck with tea leaves.”

It is seldom more than a short hop from the film noir (and the detective stories on which they were based) to the supernatural horror picture, and yet the two rarely overlap directly. Indeed, in the 1940s, even horror films themselves tended toward more naturalistic explanations than speculative or supernatural ones. Which makes Night Has a Thousand Eyes a fascinating anomaly.

While Wikipedia lists Night as a “horror movie,” it is emphatically operating in the film noir register, even while it also sticks out from that crowd in a number of ways. By the same token, it isn’t really much of a horror movie, in spite of its central conceit about a sideshow mentalist who may actually be clairvoyant.

Not as well known as some of its film noir contemporaries, Night Has a Thousand Eyes nevertheless boasts an impressive set of credentials. Helmed by Academy Award-winning director John Farrow, who filmed The Big Clock, another great noir oddity, the same year, Night is adapted from the novel of the same name by Cornell Woolrich. Woolrich may be best known today as the man who wrote the story from which Alfred Hitchcock adapted Rear Window, but he was no stranger to tales that skirted horror – or occasionally jumped the line into it altogether.

Nor was screenwriter Barre Lyndon averse to crossing the two wires. Prior to adapting Night Has a Thousand Eyes, he had already written screenplays for The Lodger and Hangover Square, as well as an adaptation of his own stage play, The Man in Half Moon Street, which would later be adapted again, by Hammer Films, as The Man Who Could Cheat Death. Even Dark Intruder from 1965, one of the last entries in Lyndon’s filmography and one of the earliest films to dabble in Lovecraftian horror, is a combination of supernatural and detective stories.

And that’s just (some of) the talent behind the camera. In front of it, we have Edward G. Robinson and Gail Russell, whose star was on the rise following another supernatural horror film, 1944’s The Uninvited. To a huge extent, though, this is Robinson’s show. Indeed, a large portion of the movie is just him talking – and it’s to his credit that Edward G. Robinson just talking is still completely arresting.

While the meat of the film may belong to Robinson and his narration, John Farrow gets plenty of opportunities to demonstrate his directing chops. After a shadowy and atmospheric opening at a train station, there are a couple of really good tracking shots throughout the film’s running time that are impressive but never showy. And as a lifelong resident of Kansas (for better or worse), it’s nice to see a film where not one but two major plot turns take place in Wichita – even if the majority of the action is still set in LA.

The speculative element in Night is simple enough: Robinson plays a phony but talented stage mentalist who suddenly begins having flashes of true precognition – or so he says. These flashes enrich him and his friends, but ultimately destroy his life, as he sees the fates of those around him, and is powerless to prevent them.

“I’d become a sort of reverse zombie,” Robinson’s unmistakable voice intones in the film’s extended narration. “I was living in a world already dead, and I alone knowing it.”

The real story of Night begins after all of this, though. When Robinson’s mentalist has been out of the world for years, and only checks back in on Gail Russell’s character, who is the daughter of his former fiancé and his former best friend, both of whom he abandoned due to his visions. Unfortunately, when he sees her, he also foresees her death, which sets the wheels of the film’s plot into motion.

Night Has a Thousand Eyes is an unusual noir for a lot of reasons, but perhaps the biggest is that the crime that it concerns is largely unclear until the film’s final moments. Up to then, most of the tension comes from being unaware of whether or not Robinson’s character is telling the truth. Is he in fact clairvoyant, or is he a confidence trickster who has shown up and used a series of facts about Russell’s past to make it look like he can see the future?

Even if you’re pretty sure you know going in – it is difficult, after all, to not have been spoiled at least a little bit on a movie that is three-quarters of a century old – the unspooling of the film does a good job of keeping you on your toes, offering up credible leads in both directions.

The year before Night Has a Thousand Eyes hit screens, another film noir was released, the Robert Mitchum-starring Out of the Past. That picture has an exchange of dialogue that is maybe the ultimate summation of the film noir as a form. “Is there a way to win?” a character asks Mitchum’s protagonist over a game of chance. “There’s a way to lose more slowly,” he replies. Night Has a Thousand Eyes posits that there may not even actually be that – that even being able to see the future may not enable you to do anything about it.

In spite of this, the note at the end of Night is more hopeful than many of its peers, which is another place where it bucks the film noir trend. Compare it to another noir released the year before about a sideshow mentalist, Edmund Goulding’s Nightmare Alley, which was remade in 2021 by Guillermo del Toro and which features one of the bleakest endings in the annals of the genre. By contrast, while there is more than enough tragedy to go around in Night Has a Thousand Eyes, it is perhaps less-than-usually cynical about the merits of the human spirit, especially as the credits roll.

———

Orrin Grey is a writer, editor, game designer, and amateur film scholar who loves to write about monsters, movies, and monster movies. He’s the author of several spooky books, including How to See Ghosts & Other Figments. You can find him online at orringrey.com.